You may be wondering why I proclaimed today to be "Best Leaf Color Day." After all, beautiful scenery is subjective, just like the best time of the year and the location to view it.

Hence, a drive down memory lane took me to a spectacular drive, especially in the fall. Skyline Drive is a 105-mile road that meanders through the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. Just a hop, skip, and a jump from Charlottesville, where I got my degree. (Spare me the "Was Thomas Jefferson there with you" old age jokes. Not funny. And he was there a few years before me.)

If you're not able to enjoy the colors in person, perhaps a lesson about how they form might (but probably won't) suffice. Nonetheless, here comes a Dreaded Chemistry Lesson From HellTM that will explain the origin of these colors.

Of course, neither Steve nor Irving gets to experience fall (or any other season down there), but let's bring the old cranks up for a bit and see if they can help explain why leaves come in such a variety of colors depending on the season. It's all chemistry.

Although Steve (left) and Irving are perpetually miserable individuals even they can have a joyful moment. Both are big fans of The Mamas and the Papas (especially Michelle Phillips). This, plus the advent of autumn, got them, albeit temporarily, into a rare festive mood.

To demonstrate why leaves change color, there's a cute experiment I used to supervise when I was a teaching assistant at UVA, while trying to ensure that pre-med students didn't blow themselves up in organic chemistry lab. It’s called thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Here's how it works.

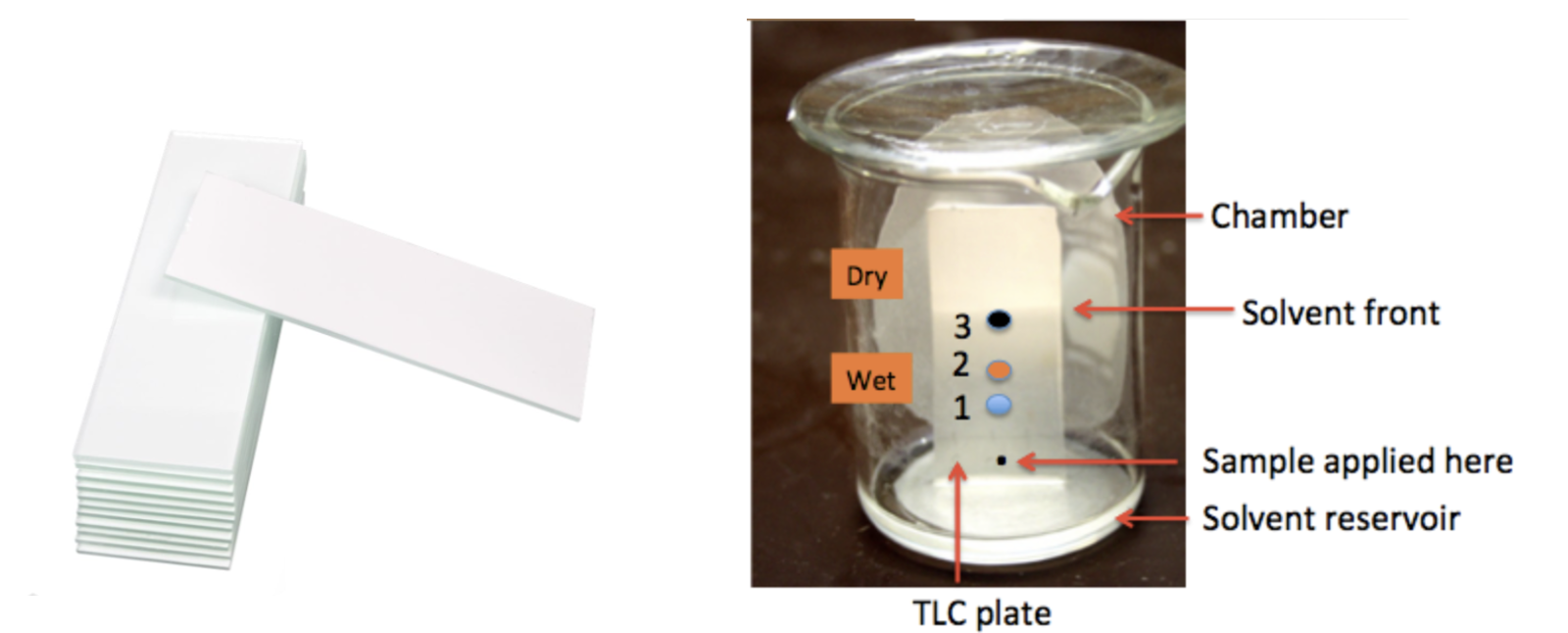

TLC plates (Figure 1, Left) are typically glass with a silica gel coating, which acts as a medium for the pigments to separate. First, a tiny amount of the sample is applied to the plate, about one-quarter of an inch from the bottom. Then, the plate is immersed in a solvent inside a developing chamber, which can be a covered jar, beaker, or other container. As the solvent runs up the plate, the compound(s) at the origin move along with it. Different compounds move at different rates, depending on their polarity, and this enables the chemist to identify how many different chemicals are in the mixture and (often) what they are.

Figure 1. (Left) Silica gel TLC plates (Sigma-Aldrich catalog). (Right) A typical TLC development. The small black dot near the bottom represents the crude mixture to be separated. Upon development, three different compounds are present: blue, orange, and black, in decreasing order of polarity. This is a picture, not a real plate. In real life, the spots don't usually separate so cleanly, nor are they perfectly round or colored as shown here. Image: J-Man Photo LLC.

Using TLC to see leaf colors

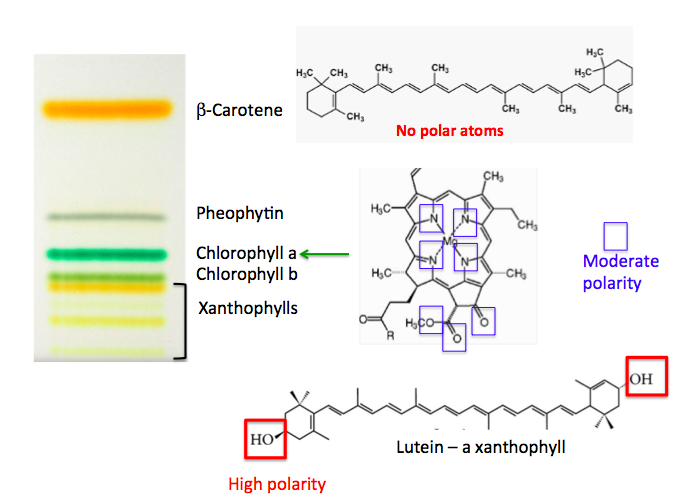

Rather than leaves, spinach is used because it contains more pigments. The leaves are ground up with a mortar and pestle in the presence of a solvent and sand; the solvent extracts the leaf pigments. In the example shown in Figure 2, the mixture is applied as a thin band (rather than a spot) to the plate, which is put into the developing chamber. Much as before, the solvent moves up; it carries the pigments with it, separating them into colorful bands, but note the number of different compounds and their colors. This simple experiment shows us the different pigments found in leaves—orange, yellow, and green—the same colors we see as the seasons change.

Figure 2. Thin-layer chromatography of spinach extract. The chemical structures are shown to the right of each component.

Polarity or the lack thereof

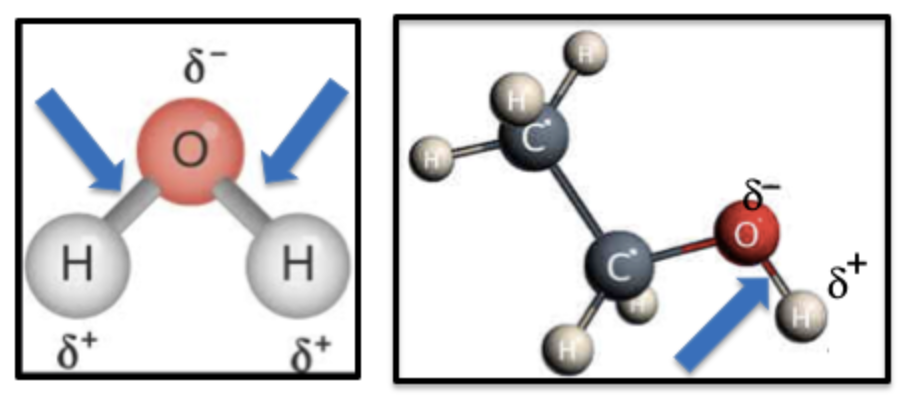

In chemistry, polarity describes how electrons are shared in a bond. When the sharing is uneven, small positive and negative charges form, like tiny magnets. Water and alcohol are polar because oxygen pulls the electrons closer, leaving one side slightly positive and the other slightly negative.

Carbon and hydrogen, by contrast, share electrons equally, making their bonds non-polar. Think oils and gasoline. This explains the old rule of “like dissolves like”: water mixes with alcohol but not with oil.

Figure 3. The bonds (blue arrows) in water (Left) and ethanol (Right) are polar because oxygen strongly attracts electrons, making one side of the O-H bond slightly positive and the other slightly negative.

TLC and Separation

On a TLC plate, polarity determines how far pigments travel. Non-polar compounds like β-carotene (orange) zip to the top. Chlorophyll (green), which contains oxygen and nitrogen atoms, sticks in the middle. Lutein (yellow), with two hydroxyl groups (–OH), is the most polar and clings near the bottom.

The pattern of pigment bands shows how “sticky” each compound is: the less it sticks, the farther it travels.

Why do leaves change color?

Well, it's not "Monday, Monday" (another of Steve and Irving's favorites). It's "Thursday, Thursday," one day after the Yankees, who sleepwalked through the ALDS, got utterly mutilated by the Blue Jays. For fans, it's the end of the week, month, and year...

Unlike the Yankees, leaves never disappoint in October.

(A version of this article appeared last fall when the leaves (and, yet again, the Yankees) showed their true colors.

NOTES:

(1) Synthetic organic chemistry is a technique for converting one chemical compound to another. This is precisely what Walter White did when he converted Sudafed to methamphetamine.

(2) There are many more chemical compounds present in spinach. Some are not colored, so they can't be seen. Some are present in amounts too small to see. And there can be bands within each band that just happened to run up the plate the same distance (co-elution).