Hypertension or high blood pressure is a common medical problem. It is episodically controversial as one or another guideline continues to lower the diagnostic criteria for initiating treatment, creating a larger and larger market for physicians and pharmaceutical to treat. Part of the reason we treat high blood pressure is that it makes the heart work harder; it takes more muscular strength to develop a pressure of 150 than 120. And harder work for an aging heart is intuitively a bad idea. On the other hand, when the arteries are partially clogged a higher pressure may be necessary to get the blood everywhere it needs to go.

A study reported in the European Heart Journal comes to a surprising conclusion, blood pressure control is not always good for you; in fact, it may increase your chance of dying. The study looked at Germans age 70 or greater involved in a long-term study evaluating kidney function – patients on dialysis or transplanted were excluded. Approximately 80% of the participants were treated for hypertension and were then stratified into two groups; those with “normalized” blood pressures, e.g., 140/90, meeting acceptable guidelines, let’s call them the well-controlled. The second group had higher blood pressure readings, despite medications they remained outside our recommendations, let’s call them less-controlled. The mean follow-up was six years.

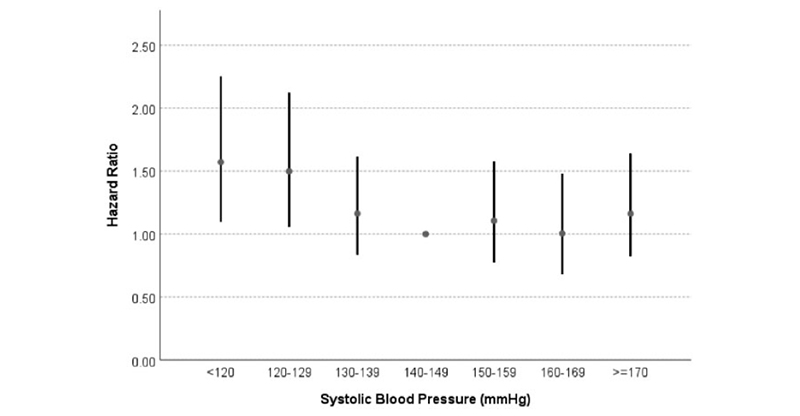

- The well-controlled patients had a 25% greater chance of all-cause mortality compared to those with less-controlled high blood pressures.

But if you look at the differences between the two groups, the “normalized” well-controlled were more likely to have had a heart attack, so perhaps that played a role. The researchers performed further analysis to isolate the cardiovascular patients and older patients; from a p-hacking perspective, this analysis was part of the study design and not based on the findings.

- If there were no prior cardiovascular events, the well-controlled and less-controlled had the same incidence of all-cause mortality.

- When stratified by age for patients age 70 to 79, again, well-controlled and less-controlled had the same incidence of all-cause mortality.

If the degree of blood pressure control did not help or hurt these groups, who did show benefits or harms?

- If there were prior cardiovascular events, those patients with well-controlled blood pressure control had a 56% increase in all-cause mortality.

- And similarly, for individuals over 80, well-controlled blood pressure was associated with a 34% increase in all-cause mortality compared to the less controlled cohort.

Here is a graphic presentation, with a U or J-shaped curve meaning mortality increases when the blood pressure is too low and too high.

That is a shape consistent with the idea that blood pressure changes autoregulate to find a “Goldilocks” range, increasing pressure to increase blood flow to organs and compensate for declining function – that like somewhat clogged pipes, perhaps a little higher pressure is a good thing.

Other, shorter-term studies in the elderly suggest that lowering the blood pressure to 120 resulted in better outcomes, so a definitive understanding eludes us. But if we are to practice personalized medicine than we have to recognize that blanket guidelines are inadequate, and we may have to face the realization that there are many subgroups all requiring different care. For such a common and prevalent disease, hypertension still has many lessons to teach us, about standardization, as well as being a little more humble and a little less eminent in our guidelines and pronouncements.

Source: Control of blood pressure and risk of mortality in a cohort of older adults: the Berlin Initiative Study European Heart Journal DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz071