By any measure, plastic waste is a global headache. Whether in the form of microplastics infiltrating the food chain or mountains of discarded water bottles choking shorelines around the world, it poses a nasty problem for which no easy solution currently exists.

Using some clever microbiology combined with organic chemistry, Steven Wallace and colleagues at the Institute of Quantitative Biology, Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Edinburgh in Britain, have shown for the first time that polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the plastic used to make single-use water bottles, is one of the worst offenders in terms of sheer volume. An estimated 500 billion PET bottles are manufactured annually. Although PET is the most widely recycled plastic, only about one-third of it is actually reprocessed.

The Edinburgh paper, recently published in the journal Nature Chemistry, will have little impact (at least on this scale) in addressing the issue of plastic pollution. However, the group has figured out how to bioengineer it into acetaminophen (Tylenol, APAP), which, ironically, may not even help with the headache this story might give you.

(Un)Common E. coli to the Rescue

But first, a little chemistry is required to prepare the “meal.

Escherichia coli, also known as E. coli, is one of the most abundant bacteria on Earth. It was genetically modified (and the world did not end) by introducing two extra genes from other organisms: Agaricus bisporus, which is found in certain mushrooms, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a common bacterium found in soil and water.

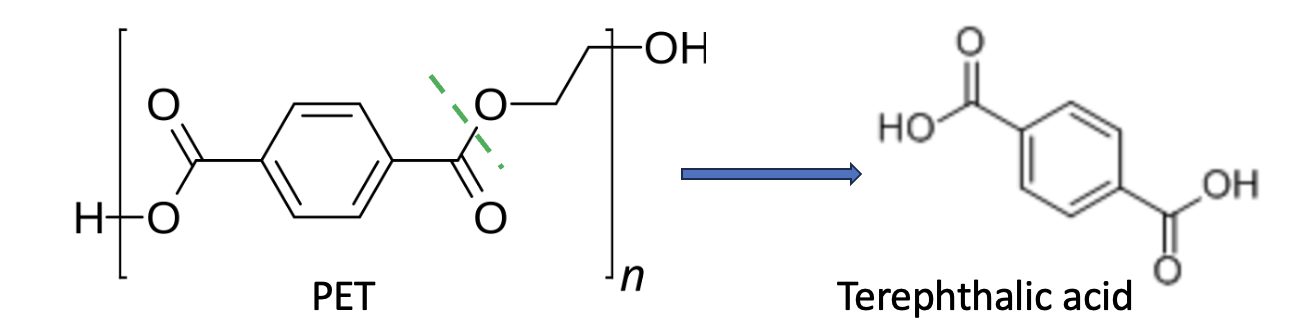

Here's how it works. Before the microbes were turned loose, some chemistry was required. Although there have been reports of using microbes that break down PET, the UK group employed a simpler method invented by the Mesopotamians in 2600 BC, known as saponification, aka soap-making, to hydrolyze PET into a smaller, microbe-friendly building block called terephthalic acid (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (Top) Saponification: Potassium hydroxide and water hydrolyze the ester bonds (green hatched lines) in fats or oils to give soap. (Bottom) Similarly, PET is a type of polyester polymer. It, too, can be hydrolyzed by a strong base, breaking down to form terephthalic acid (TPA), which serves as the "food source" for the microbes in the next step.

Modified TPA is Fed to Bacteria.

Until now, the engineered E. coli have been passive participants — but this is where they finally take center stage. This step is the heart of the study, and it's a clever example of synthetic biology as well as a textbook example of how genetic modification, far from being a scientific boogeyman, is a powerful and essential tool in modern biotechnology.

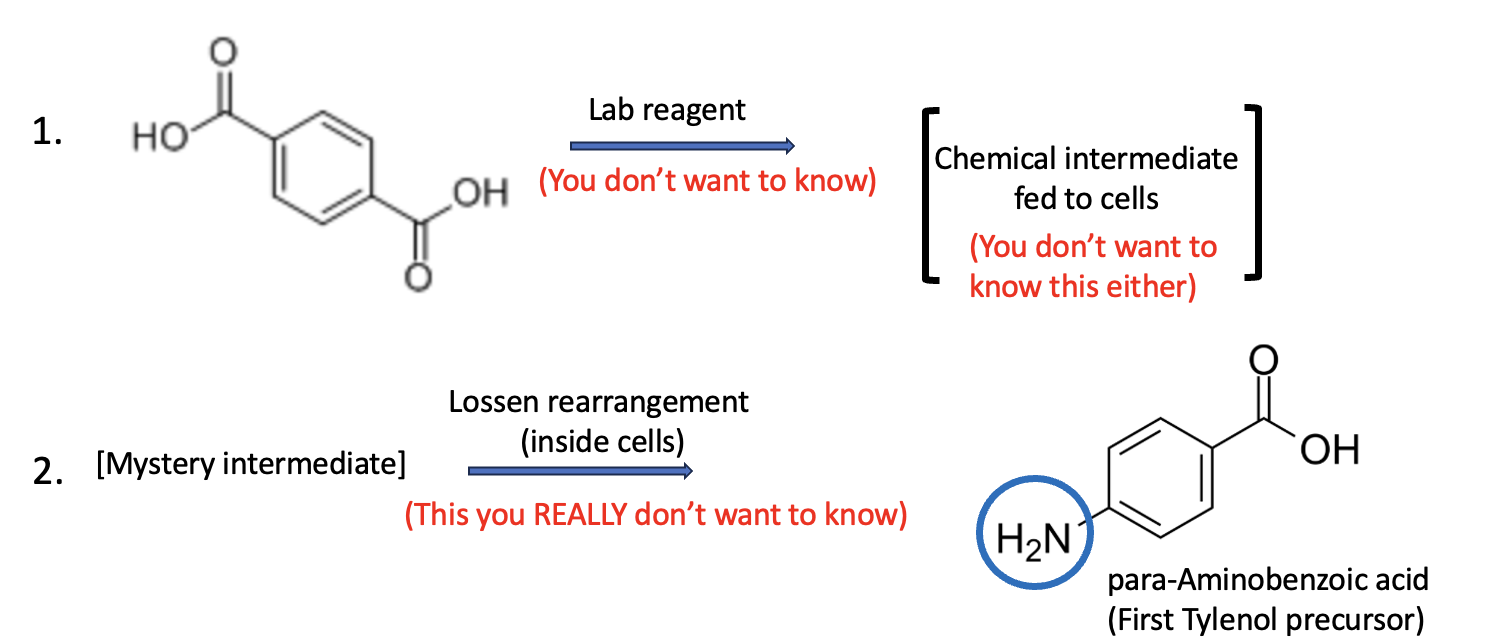

The TPA (terephthalic acid) obtained from the chemical breakdown of PET bottles was first converted into a compound called an O-acyl hydroxamate (a chemical transformation beyond the scope of this article). This intermediate is then introduced to the genetically engineered E. coli.

Once inside the bacterial cells, the O-acyl hydroxamate undergoes a Lossen rearrangement — a phosphate-triggered rearrangement (also beyond our scope) —which ultimately produces p-aminobenzoic acid (PABA). The bacteria then utilize this PABA as the first step in the biotransformation process. (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Step 1. Terephthalic acid (TPA), obtained from the basic hydrolysis of the bottles, is converted in the lab to an intermediate called an O-acyl hydroxamate. The structure is not shown here, as it is beyond the scope of this article. Step 2. The O-acyl hydroxamate is fed to the GM bacteria, where it undergoes a phosphate-catalyzed Lossen rearrangement. Note that this reaction has "traded in" one of the carboxylic acid groups for an amino group (blue circle), forming para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), which is essential for the formation of APAP.

Biotech joins the party

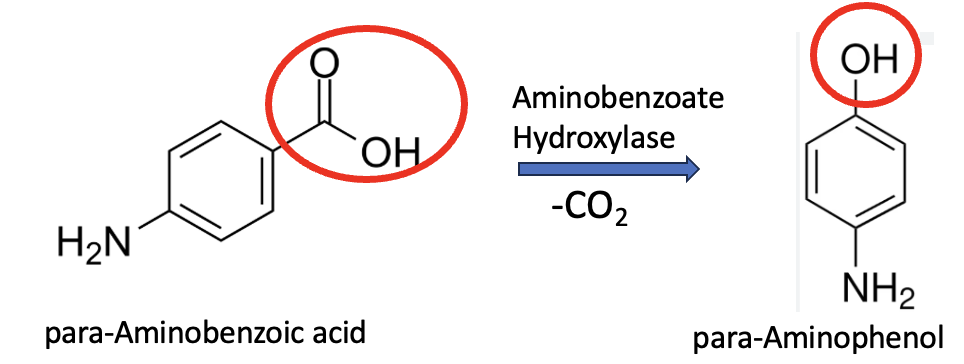

The first enzymatic step [1] now kicks in, catalyzed by aminobenzoate hydroxylase—an enzyme encoded by the ABH60 gene from Agaricus bisporus. This process is known as decarboxylative hydroxylation – the removal of one molecule of carbon dioxide and leaving behind a hydroxyl group. This brings us very close to APAP (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The conversion of PABA to para-aminophenol is catalyzed by the enzyme Aminobenzoate Hydroxylase. The transformation of the carboxylic acid to the hydroxyl group is highlighted by the red ovals.

Final Step: Conversion of p-Aminophenol to Tylenol

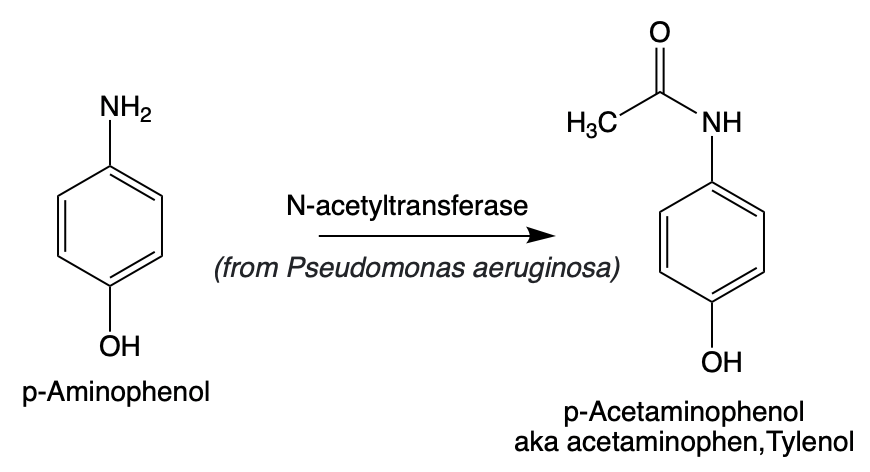

This final step, acetylation, is a common reaction in both drug biosynthesis and metabolism (Figure 4). Here, an acetyl group is enzymatically added to p-aminophenol by arylamine N-acetyltransferase, encoded by the panA gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. With this transformation, the pathway is complete: a discarded plastic bottle has now been converted into one of the world’s most widely used medications—acetaminophen.

Figure 4. The final step, the transformation of p-aminophenol into Tylenol, is an acetylation reaction catalyzed by N-acetyltransferase.

A Surprise: This is gain-of-function research

An essential but often overlooked aspect of this research is that the genetically modified E. coli used to produce acetaminophen qualifies as a gain-of-function (GoF) organism — one that has acquired a new trait through molecular engineering. Does this make it scary?

My colleague, Dr. Henry Miller, who was the founding director of the FDA's Office of Biotechnology in the 1980s, says no:

The very mention of gain-of-function causes the anti-GMO crowd to freak out. However, this study is a good example of the unwarranted concerns about GoF organisms in general, as well as the calls to regulate them as if they were all bioweapons. Note that the organism would be captured for regulation by EPA's TSCA (the Toxic Substances Control Act) because it's genetically modified, but might be subjected to especially onerous regulation because of the GoF factor.

Bottom line

The science behind this study is original and quite clever. Will it provide a practical method for reducing the plastic waste that is polluting the planet? Probably not; there is simply too much of it.

Finally, if this chemistry-loaded article has given you a headache, you could try some Tylenol, which is a barely effective analgesic – something I've written about in the past. [2] Or, perhaps you'll find similar relief by chewing on the water bottle.

NOTES:

[1] Although the conversion of terephthalic acid to PABA occurs in the cell, it is a chemical reaction, catalyzed by endogenous phosphate. No enzyme is involved.

[2] Here's one of many examples.