Critical Medicines Are a Matter of National Security

There are approximately 288 critical medicines identified by national and international experts as indispensable for patient care; their absence causes immediate harm. The World Health Organization defines "indispensable" with respect to basic healthcare, while our FDA’s criteria are a bit broader. However, in both instances, these medications have no therapeutic substitutes, or delaying treatment can dramatically worsen outcomes.

While a preponderance of these medications are “small molecule drugs,” like heparin, an anticoagulant, or amoxicillin, an antibiotic, or opioid pain medications, the lists also contain more complex drugs. For example, insulin, a biologic peptide, or Adalimumab (Humira), a monoclonal antibody used in treating autoimmune disorders. From a perspective of our national health, the availability and therefore, the supply chain of these compounds, are critical national security concerns. Understanding how supply chains function, and where they fail, is essential to protecting public health. To see where fragility enters, it helps to picture the pharmaceutical supply chain as something living and flowing.

The Pharmaceutical River: How Medicine Flows Through a Global Supply Chain

To understand medicine’s supply chain, consider a metaphorical pharmaceutical river.

It begins with multiple headwaters; active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) plants on several continents feed the same stream, so if one spring dries, others keep the flow steady. Each of these streams has a wide, deep main channel, with spare capacity (depth) and standardized equipment (width) that let production surge or pivot quickly. Enhancing its resilience are well-placed reservoirs, strategic stockpiles at key junctions, releasing extra “water” during spikes in demand or when an upstream gate closes. The final distribution involves co-managed interconnected tributaries & bypass canals. Multiple ports, trucking lanes, and air-cargo options allow traffic to divert around blockages without lengthy detours. Additionally, governments, firms, and aid groups agree in advance on who opens which sluice gate when storms hit. That co-management requires information, water gauges giving regulators and companies an early warning before levels drop.

Supply chain resilience comes from recognizing how money, design choices, and information flows interact. Three invisible currents determine whether our pharmaceutical river stays healthy.

- Reinforcing loops: Prudent financial margins support extra capacity and backup facilities. Thin margins, by contrast, starve the system and make it brittle.

- Hidden trade-offs: Cost-cutting strategies that reduce inventory or consolidate suppliers may lower short-term expenses but shrink reserves, leaving the system less adaptable.

- Cascading failure: When single sources or lean buffers become choke points, a minor disruption can close the main channel entirely. Resilient systems bend but do not break — rerouting flow when trouble hits.

In the real world, however, the river rarely runs smoothly

Reality Bites: Real-World Disruptions

In the ideal, redundancy, transparency, and agility allow both flow and “lowish” costs. Of course, the real-world features disturbances, often, but not always man-made, that disturb flow.

For example, an unexpected pandemic or local outbreak can double demand, “breaching” reservoir capacity. Tariffs, sanctions, or export bans (for which there have been 60 in the last few years) block access to low-cost sources. Country-specific regulatory measures over quality and labeling, acting like “small dams,” reduce or delay the availability of alternative sources and routes. In essence, the journey from chemical to pill is a global relay, where each hand-off becomes more valuable, but also more exposed to “hiccups” in trade, politics, weather, and bad luck. Those risks grow when economics, not medicine, sets the pace.

It’s about the Benjamins

Critical medicines are life-saving, but undervalued products: mostly old, off-patent molecules sold cheaply, made in a handful of large plants, and traded through highly concentrated routes.

- Generics make up >80 % of global prescriptions but only 20–30 % of total pharma revenue; critical medicines dominate this segment

- The volume-value gap drives firms to cluster capacity in a few facilities, discouraging redundant plants. A decade of consolidation has left supply chains “geographically concentrated and vulnerable to disruptions.”

- Generic drug makers operate with narrow margins; extra costs threaten manufacturing. Fixed reimbursement rates and pricing exacerbate this, so costs are not easily passed “downstream” to insurers or users.

- Critical medicine prices are inelastic because patients need them even in the face of rising costs. Price increases do not automatically result in less demand. This is compounded when we consider the far more expensive biologics, where few substitutes are available.

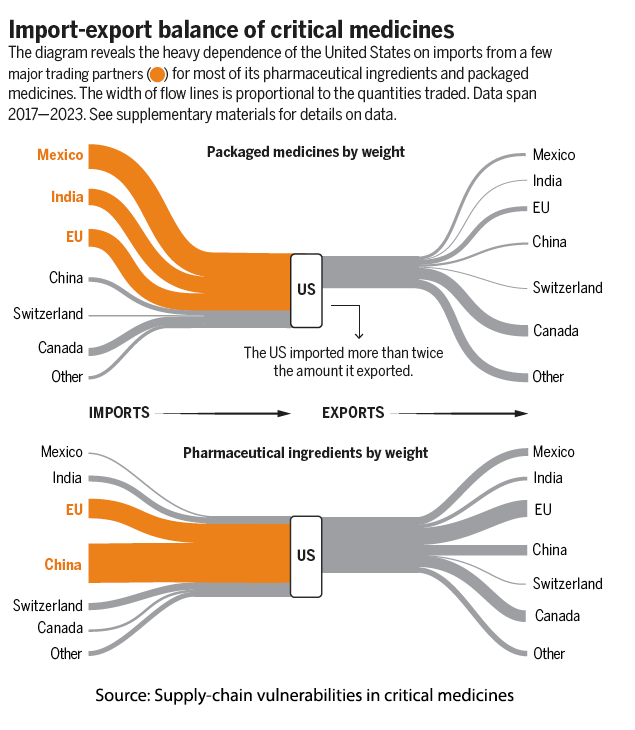

Because critical medicines have low commercial value but high clinical importance, exporting nations hold significant leverage. Tariffs or export bans can hurt importing countries far more than exporters. For instance, nearly 30% of all packaged critical medicines used in the US come from Mexico — yet they represent less than 0.1% of Mexico’s total exports to the U.S. Similarly, about 40% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients we rely on originate in China, but they account for less than 0.2% of China’s exports to the US. These flows are vital to us but economically minor for them — an asymmetry that magnifies our vulnerability. That vulnerability becomes stark when we look inside America’s own medicine cabinet.

Because critical medicines have low commercial value but high clinical importance, exporting nations hold significant leverage. Tariffs or export bans can hurt importing countries far more than exporters. For instance, nearly 30% of all packaged critical medicines used in the US come from Mexico — yet they represent less than 0.1% of Mexico’s total exports to the U.S. Similarly, about 40% of the active pharmaceutical ingredients we rely on originate in China, but they account for less than 0.2% of China’s exports to the US. These flows are vital to us but economically minor for them — an asymmetry that magnifies our vulnerability. That vulnerability becomes stark when we look inside America’s own medicine cabinet.

Resupplying our Medicine Cabinet: Building Resilience

A surprisingly slender production spine still stocks America’s medicine cabinet. Nearly half of the active ingredients that keep intensive-care wards running originate from a single country, and most domestic plants that turn those powders into finished doses are already running flat-out. When even a modest import hiccup occurs, the nation can drain its hospital inventories in little more than a month because surge lines and safety stock were stripped away to save pennies.

Tariffs look tempting in a headline: slap a duty on imported ingredients, the story goes, and manufacturing will spring back into the US. But the arithmetic of critical medicines is unforgiving. Tariffs address the symptom of foreign dependence without touching the underlying condition, structural fragility. Generic producers, already surviving on razor-thin margins, cannot absorb even modest price jumps; so prices rise. If faced with cost ceilings, it is easier to close a plant than to suffer losses. Worse, tariffs do nothing to create spare capacity, qualify alternate sites, or reveal where the next shortage is brewing. They can even backfire, prompting exporting countries to impose their own controls, turning a cost problem into a supply drought.

A more durable fix requires rethinking incentives, not just penalties.

Designing a Resilient Future for Critical Medicines

Policymakers have begun to design more constructive responses. Tax credits could support second suppliers for high-risk drugs, ensuring at least two qualified sources for each. Subsidies for surge capacity could fund idle production lines that can be activated in emergencies. The proposed Mapping America’s Pharmaceutical Supply (MAPS) Act would trace each drug from raw chemical to pharmacy shelf, offering real-time visibility into inventory and bottlenecks — though it remains stalled in Congress. Yet policy sketches matter little if the economics still punish redundancy. Adjusting reimbursement formulas to reward manufacturers that maintain dual sourcing, backup sites, and data transparency could pay a “resilience dividend.” With creative design, the U.S. can strengthen its pharmaceutical backbone without losing the affordability patients depend on.

With the right incentives, policies like the MAPS Act, and a renewed commitment to redundancy over razor-thin efficiency, the US can transform a fragile pharmaceutical river into a steady, sustainable flow — one that protects both lives and sovereignty when the next disruption arrives.

Source: Supply-chain vulnerabilities in critical medicines: A persistent risk to pharmaceutical security Science DOI: 10.1126/science.adx0871