Mesothelioma is really bad news

Mesothelioma doesn’t move fast, but it doesn’t stop either. Once it starts, it keeps going. Decades of research and nothing that's been thrown at it has changed the outcome in any meaningful way.

Doctors have tried nearly everything: small molecules (aka chemo drugs—some of them straight-up poisons—that kill dividing cells, cancer and normal alike), monoclonal antibodies (lab-made proteins that stick to one specific target), and gene therapy (DNA packages meant to replace or shut down a bad gene).

The small molecules are still the main tools. That’s not great. The first-line drug is cisplatin, and it’s a monster, one of the most toxic chemotherapy drugs we use, and that’s a crowded field.

Cisplatin’s job is "simple": it cross-links DNA so the cell can’t divide. It doesn’t care what kind of cell it hits. Cancer, gut lining, and hair follicles are all fair game. The side effects are just about what you’d expect: nerve damage, hearing loss, severe vomiting, and kidneys that sometimes don’t recover. (Some oncologists call it "vomitoxin").

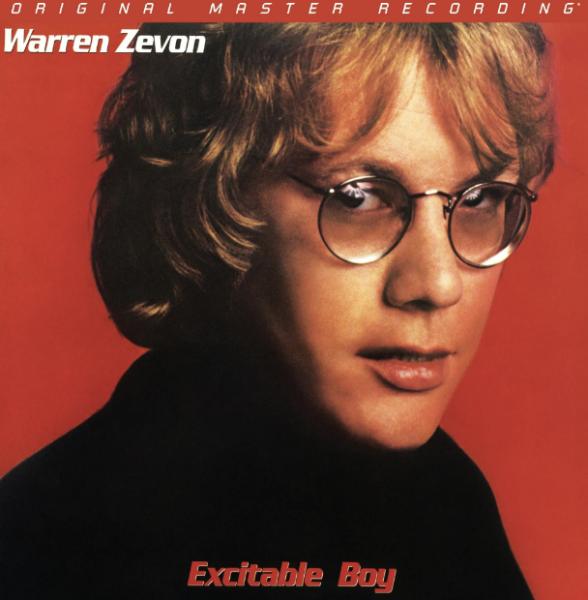

So it’s not surprising that Zevon chose to skip chemo. He wasn't a big fan of medicine, but he understood the math. A few more months of life — most of it sick, weak, and miserable — isn’t much of a trade. That’s the problem with some of our best weapons against cancer – they might work, but they work brutally. And with mesothelioma, they barely work at all.

Any hope on the horizon?

Some, but nothing soon.

After years of failure, a group led by Johns Hopkins and Georgetown researchers published a study in Nature Medicine (2025) testing a new approach: immunotherapy given before and after surgery.

Thirty people with operable pleural mesothelioma (a cancer on the lining of the lung) were treated. Half got nivolumab alone—an antibody that blocks PD-1 [2], a brake on immune cells. The other half got nivolumab plus ipilimumab, which also blocks CTLA-4 [3], another brake. The idea is simple: take the brakes off the immune system so it can see and attack the tumor.

Patients got three doses before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy), then surgery, then a year of nivolumab afterward (maintenance therapy).

About 80 percent made it to surgery safely. The side effects were mostly immune-related—fatigue, rash, temporary inflammation of the colon (colitis) or liver (hepatitis); they were controllable with steroids. Some tumors shrank or showed very little live cancer at surgery (pathologic response).

The researchers also measured ctDNA [4]—tiny fragments of tumor DNA circulating in the blood. When ctDNA disappeared after treatment, patients tended to do better; when it lingered, relapse was more likely.

What this study really shows isn’t a cure; it’s a shift. We’re finally starting to connect the biology to the outcome—to understand why some patients respond and others don’t. That’s not marketing language about “precision medicine”; it’s just logic we should have been using all along.

The drugs—big protein antibodies, not pills—aren’t simple. They’re expensive, hard to make, and come with their own problems. Bigger trials are already planned, and they’ll take years. But after so many dead ends, even a small, consistent signal is worth paying attention to.

What comes next?

Unfortunately, not much soon.

Early results like this have to be confirmed by larger studies, a more diverse patient population, and a longer follow-up time.

Even if the immune therapy holds up, it won’t appear in clinics overnight. These treatments require careful dosing and monitoring and are costly. Regulators will want evidence that they truly extend life, not just shrink tumors. Insurers will want to know which patients truly benefit. (And they will probably reject it anyhow.)

Still, the study gives researchers something to chase—an immune pathway, a genetic signal, a question that can be tested again. That’s how progress happens in medicine: slowly, with repetition and stubbornness.

Hope, such as it is

We’re nowhere close. But think about what happened with breast cancer once doctors learned to separate estrogen-receptor-positive tumors (those that grow in response to estrogen) from HER2-positive ones (driven by a growth-factor receptor called HER2). That single insight turned one large, untreatable disease into several smaller, more manageable ones.

This will be harder. But so were those, once. Cancer progress rarely arrives with a flourish; it creeps in through journal articles. That’s what progress looks like at the start. It’s not exciting, but it’s real, and that's no different here.

Let's close with another iconic Zevon line

“I probably should’ve gone to the doctor sooner”

Notes

[1] Mesothelioma is not lung cancer. It arises from the pleura—the thin membrane that lines the lungs and chest wall, not from lung tissue itself.

[2] PD-1 (programmed death-1): A receptor on T cells that acts like an off-switch. When PD-1 binds to its partner PD-L1 on tumor cells, the immune cell shuts down instead of attacking. Blocking PD-1 keeps the immune response switched on.

[3] CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4): Another checkpoint receptor, active earlier in the immune response. When CTLA-4 engages its partner, T cells stop multiplying. Ipilimumab blocks CTLA-4, allowing more T cells to expand and attack.

[4] ctDNA (circulating tumor DNA): Tiny fragments of tumor DNA that leak into the bloodstream when cancer cells die. Detecting ctDNA means tumor cells are still active; if it disappears, treatment is probably working.