“So the left hemisphere needs certainty and needs to be right. The right hemisphere makes it possible to hold several ambiguous possibilities in suspension together without premature closure on one outcome.”

― Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

Iain McGilchrist argues that the brain’s hemispheres approach the world differently: the left tends toward certainty and closure, while the right is more comfortable holding ambiguity.

The Brain’s Two Modes of Explanation

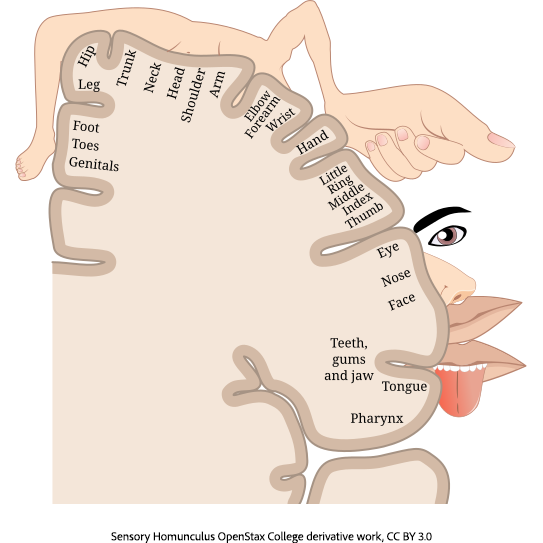

Our brains are not symmetric in form or function. Despite that knowledge, we often believe we can assign inalienable characteristics to areas. One need only remember the homunculus, a somewhat distorted neurologic mapping of form and function. There does appear to be some neurologic “truth” to the idea that the left and right hemispheres display some consistent processing biases. In addition to McGilchrist's description, we often describe the left brain as analytical and the right as more creative. Paul Kingsnorth, in his current bestseller, Against the Machine, points to the left brain as asking how questions – details, mechanisms, stepwise causality served by tools, models, and measures. The right brain is more interested in why questions – context, relationships, purpose, serviced by ethics, values, and systems or holistic thinking. Yet these descriptions are best understood as metaphors rather than rigid assignments. The corpus callosum, the brain’s largest white-matter tract, enables constant communication between hemispheres, meaning that most real-world thinking depends on their collaboration rather than separation.

This raises a broader question: how might these cognitive tendencies shape the way we communicate scientific ideas? Could some of our difficulty in communicating science come down to whether we are asking how or why questions without the balance necessary to influence what we study, what we conclude, and which problems we prioritize?

Where Communication Breaks Down

“How” questions are the cultural touchstones of science. They tend to be reductionistic and quantifiable, making them well-suited to controlled experiments and technical solutions. Much of modern medicine—including my own surgical training—relies on such questions: How effective is bypass surgery compared with angioplasty? How do pre-operative antibiotics reduce infection risk? Pursuing these questions has led to significant advances, from antibiotics to emerging forms of precision medicine.

Yet “how” questions have limits. They often address symptoms more readily than root causes and can obscure downstream consequences—such as the rise of antibiotic resistance that followed widespread antibiotic use. If “how” questions excel at producing tools, “why” questions guide our understanding of how those tools fit into a larger human story.

Why questions have always been more challenging to formulate and solve, they are the stories we tell ourselves based on the answers to our how questions. Why questions frame our experience within narratives, values, and meaning. Scientists are human, subject to the same lapses we all experience. Just as there is no rational economic “animal,” we would be hard-pressed to find a wholly rational scientist, especially when they seek to address why questions. When tackling "why" questions, we all may:

- Notice evidence that supports what we already believe (confirmation bias)

- Prefer conclusions that protect our identity or emotions (motivated reasoning)

- Resolve conflicts between facts and beliefs by adjusting the story (cognitive dissonance reduction)

- Simplify complex systems into linear narratives

- Feel social pressure to adopt group-reinforcing explanations

- Overestimate understanding simply because a narrative feels coherent

Scientific methods help mitigate these tendencies, but they never eliminate them. These vulnerabilities become especially visible when "why" questions intersect with public health and politics.

Secretary Kennedy has been asking a lot of 'why' questions about vaccines, food coloring, food additives, and fluoride, to mention just a few. And while why questions concern themselves with long-term impacts, feedback loops, and, dare I say, equity, they are more challenging to quantify, which creates greater uncertainty and, for some, on both sides of the aisle, distrust.

A Case Study: COVID-19

Early in the pandemic, when we faced a novel, unknown viral foe, public health measures relied heavily on the answer to how questions. Operation Warp Speed was initiated, and we sought and found technical answers, e.g., stand 6 feet apart, wear a mask, or stay home. These effective, actionable, measurable solutions produced short-term control, but by ignoring the underlying 'why' questions posed by psychology and culture, the same measures produced weak, and increasingly controversial, long-term transformations. It was the answer to a why question, the “search” for lifestyle and identity that remains at the heart of all our arguments about following the science. These dynamics become even clearer when we look at how policies are formed.

The how questions and their answers are great for policy-making, providing measurable outputs, creating standards, and offering one-size-fits-all guidance that lets a policy or project scale. Of course, the same metrics bring along technocratic, top-down management that is often disconnected from local public values around hard-to-measure social determinants. How policy questions ask how we can reduce autism and provide us with greater diagnostics and care resources. But it is the why of increasing cases of autism that how policy formulation fails to address.

Why questions seek root causes, that is, causes with an s. Simple, single-factor explanations may be comforting, but they are rarely sufficient. Instead, “why” inquiries weave together biological, environmental, social, and cultural factors, some of which are difficult to measure. Because of this uncertainty, policies built on provisional answers to “why” questions can attract skepticism and controversy. Their value-laden nature does not make them illegitimate, but it does require transparency about the assumptions they entail.

Science Works Best When the Hemispheres Collaborate

Despite the great advances provided by our left hemisphere’s reductive how questions, societal questions regarding science must be integrated into our too-human society. Science becomes distorted only when one hemisphere dominates. While how generates capabilities, why generates the wisdom in their application. Science is a cultural practice, and the best of science acts like our corpus callosum, binding together and integrating the how and why. The right hemisphere frames the world through stories that allow us to live, act, and care. The right hemisphere frames the world through stories that will enable us to live, act, and care. Those why questions about meaning, value, and purpose shape our attempts to understand the “how.” Science, policy, and personal decision-making all improve when we recognize this truth and work with it rather than against it.