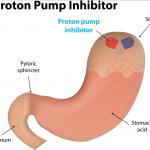

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a type of antacid first developed in the 1980s and considered the most potent medication for treating acid reflux and preventing bleeding from the stomach.

In a new study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, their use has been associated with the development of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and infection of the gut with the bacteria Clostridium difficile (CDI), two potentially fatal infections. For the majority of patients outside of intensive care units, use of PPIs has led to a net increase in hospital mortality.

It's relatively favorable safety profile and high efficacy allowed PPIs to become one of the most widely-prescribed medications. In 2014, it was the third most prescribed drug in the United States, with roughly 19.3 million prescriptions written, generating $11 billion in annual sales.

In hospitalized patients, there has been a tendency to initiate PPI therapy prophylactically. Despite implementation of standardized guidelines, routine use in the in-patient setting continues to occur with patients that may have no risk factor for upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

PPIs are frequently prescribed for prophylaxis of nosocomial [hospital-acquired] upper gastrointestinal bleeding, according to Patrick S. Yachimski, MD, MPH, formerly from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Some inpatients receiving PPIs may have no risk factors for nosocomial upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and PPIs may be continued unnecessarily at hospital discharge.

It is estimated that 50 percent of inpatients are prescribed a PPI and 15 25 percent receive this medication as prophylaxis. In an ICU setting, there's evidence to support the use of PPIs to reduce the risk of bleeding. However, evidence also suggests that initiating therapy increases the risk of developing HAP and CDI.

Based on computer simulation models, the authors of the study found that approximately 90 percent of cases where PPIs were initiated for prophylaxis, a net increase in expected mortality was observed. For 80 percent of patients who continued therapy after being discharged there was also a small increase in mortality.

Many patients who come into the hospital are on these medications, and we sometimes start them in the hospital to try to prevent gastrointestinal, or GI, bleeds, states lead author Matthew Pappas, MD, MPH, of the University of Michigan Medical School. But other researchers have shown that these drugs seem to increase the risk of pneumonia and C. diff, two serious and potentially life-threatening infections that hospitalized patients are also at risk for. Our new model allows us to compare that increased risk with the risk of upper GI bleeding. In general, it shows us that we re exposing many inpatients to higher risk of death than they would otherwise have and though it s not a big effect, it is a consistent effect.

In addition to the increased risk for HAP and CDI, prolonged use of PPIs have been linked to increased bone fracture, interference with the effectiveness of clopidogrel, a commonly prescribed blood thinner and it can cause nutritional deficiencies by interfering with absorption of nutrients.

Introducing a set of standardized guidelines, and incorporating that as part of medical training, can significantly reduce overuse and overprescribing of PPIs. Risk and benefit assessments can help determine who needs this medication and routine evaluations should be performed to determine whether PPIs should be discontinued or step-down treatment should be considered. This could potentially save lives and billions of dollars by avoiding unnecessary use.