For MAHA, the findings provide the kind of broad, cross-disciplinary evidence that Secretary Kennedy's advocacy efforts have yet to put forward. The article, from the researchers who developed the NOVA classification system, is more a polemical opinion than measured science. However, their three key findings are at the core of the MAHA mantra. This alignment sets the stage for examining how the science is being interpreted and mobilized.

UPFs Are Rapidly and Uniformly Displacing Traditional Diets Worldwide

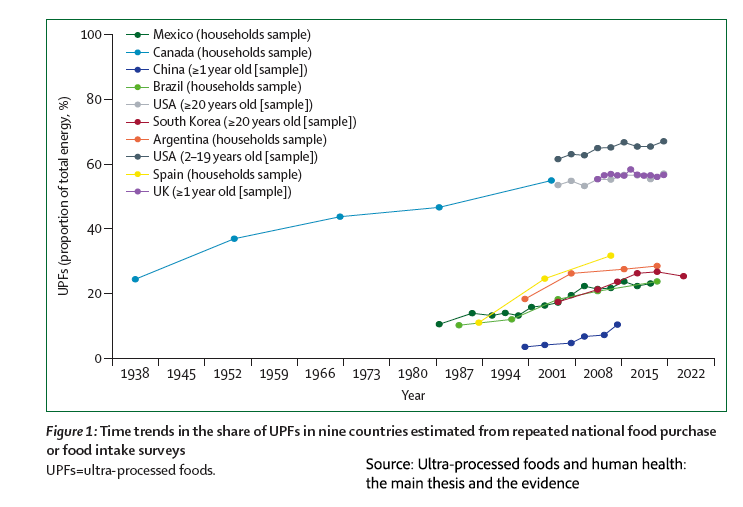

This is the first of three major claims from the Lancet series that structure both the scientific argument and MAHA’s policy lens. Across 36 countries, the share of UPFs in the diet is rising in near lockstep with the globalization of the corporate food system. The Lancet summarizes this trend bluntly:

“Together… the converging trends in consumption, purchase, and sales make evident the global displacement of long-established dietary patterns by UPFs and indicate further rapid spread in regions where UPFs are not yet dominant.”

The authors argue that this displacement is structural, not incidental, implying that policy must be early, targeted, and systemic—intervening before high-UPF patterns become entrenched. Taken together, these trends lead the authors to their second major claim about how UPFs reshape diets from the inside out.

UPFs Systematically Alter Diet Quality Through Multiple Mechanisms

“Exposure to the ultra-processed dietary pattern broadly degrades diet quality. Harmful consequences include major nutrient imbalances; multiple features that promote overeating; reduced intake of health-protective phytochemicals; and increased intake of toxic compounds, endocrine disruptors, and potentially harmful classes and mixtures of food additives.”

Of course, “degrades” is a word choice with a more pejorative meaning than simply using “alters.” For MAHA moms and others, this provides a mechanistic foundation for arguing that UPFs cannot be considered nutritionally equivalent to minimally processed foods, even when nutrient labels appear similar. This, of course, is a central thesis of the NOVA researchers that processing fundamentally alters (degrades) whole foods. It becomes the foundational gateway to target processing, additives, and formulation, not just nutrients. It also means that those doing the processing, the manufacturers, are the story’s primary villains. The third claim extends this mechanistic argument into epidemiological territory.

UPFs Increase Risk Across Multiple Chronic Diseases

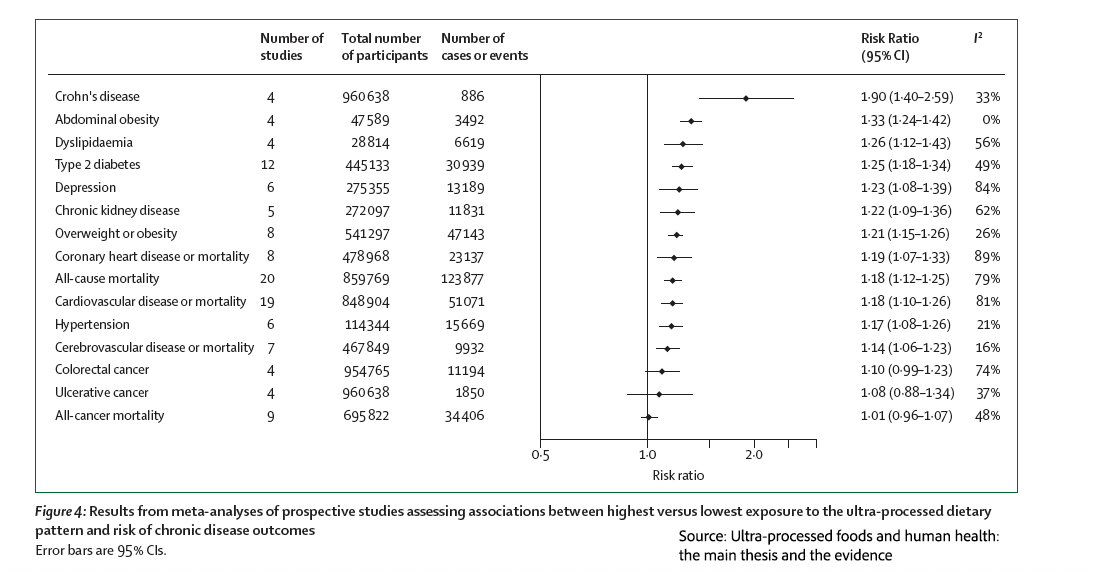

The epidemiological “signal” identified by the Lancet review raises important—but contested—questions about correlation versus causation. It is unusually broad, a fact that invites both attention and caution:

“Our systematic review of 104 prospective studies found 92 showing an association… Meta-analyses… found statistically significant associations for 12 [diseases], including: overweight or obesity; type 2 diabetes… cardiovascular, kidney, and gastrointestinal diseases; depression; and all-cause mortality.”

Indeed, the graphic accompanying this section of the study is dramatic, depicting rising UPF intake alongside elevated risk across an array of chronic conditions.

However, closer inspection and consideration are warranted. Kevin Hall’s landmark study demonstrated that calorie-dense UPFs contributed to weight gain – full stop. Because obesity is a significant risk factor for nearly all of the conditions in the chart, the observed associations may reflect calorie density rather than nutrient “degradation.” The current evidence cannot yet disentangle these pathways with confidence. Despite this uncertainty, the authors use the breadth of epidemiological evidence to frame UPFs as a population-level hazard.

The presumptive findings, primarily related to chronic illness with a strong dietary component, enable the Lancet and presumably MAHA to frame UPFs as a population-wide risk exposure similar in scale to the original environmental sins, tobacco and air pollution, justifying broad regulatory and educational strategies. [1]

Where the Evidence Meets Policy

If the first Lancet paper explained why ultra-processed foods are a threat to global health, the companion policy papers stray from nutritional science to nutritional policy. The answer, grounded in economic concerns about capitalism, is clear and unapologetic. The authors argue that UPFs have become entrenched not because individuals make poor choices, but because the system has been engineered to produce, distribute, market, and normalize these products at every turn.

“We identify four distinct dimensions of food systems that have roles in driving the production, marketing, and consumption of UPFs.”

- UPF Products: Changing What These Foods Are. Tweaking nutrients is not enough. Reformulating a soda by swapping sugar for non-nutritive sweeteners still leaves the underlying ultra-processed formulation, and the authors warn this approach can even reinforce UPF dependence. The overall aim is not to marginally improve UPFs, say by removing food coloring, but to reduce their dominance in the food supply. Regulation could and should restrict particular classes of additives, set limits on processing techniques, or establish clear criteria identifying what counts as an ultra-processed product.

- UPF Food Environments: Remaking the Spaces Where We Eat and Buy. The supermarkets, restaurants, schools, advertisements, and digital platforms where people encounter food overwhelmingly promote UPFs, shaping consumption long before a person reaches the point of “choice,” and must be structured so that minimally processed foods become the easiest and most accessible choice. Changing these environments means restricting how prominently UPFs appear, how cheaply they are sold, and how aggressively they are promoted. Front-of-package (FOP) warning labels, for instance, are highlighted as one of the most effective tools. However, the evidence for this efficacy is mixed, with a greater impact on manufacturer reformulation than consumer purchases. The results are further entangled in marketing restrictions that frequently accompany FOP regulation. The authors envision school meals dominated by minimally processed foods, taxation policies that make healthier foods more affordable, and retail rules that prevent UPFs from crowding out other options.

- UPF Manufacturers and Retailers: Constraining Corporate Power. The authors now turn to the global corporations that manufacture, market, and sell UPFs. Because in many instances transnational food, fast-food, and supermarket corporations shape consumer diets through their immense economic and political influence, policy should operate at the level of corporate behavior and market power—limiting mergers, restricting cross-brand marketing, and reducing political interference in nutrition policymaking. The authors point out that without checking corporate power, UPFs will continue expanding regardless of public health goals.

- Food Supply Chains: Transforming the Foundations That Make UPFs Inevitable. Finally, the authors remind us that UPFs became dominant through decades of agricultural, trade, and financial policies that supported monoculture crops, industrial processing, and globalized distribution networks. These transformations made ingredients like corn syrup, refined grains, and industrial oils artificially cheap, fueling an economic logic in which UPFs are the most profitable products a company can make. Reforming this system means rebalancing supply chains toward minimally processed foods by redirecting subsidies toward diversified agriculture, building local food economies, revising trade agreements, and addressing the environmental footprint of UPFs.

From these structural critiques, the authors turn to what they see as the industry’s organized resistance.

The return of the tobacco playbook

The policy papers argue that UPF manufacturers employ strategies reminiscent of the tobacco industry. According to the authors, corporate political activity—including lobbying, influencing government agencies, litigation, and shaping scientific agendas—represents the largest barrier to effective regulation. They contend that companies work to block restrictions, shape public narratives around “personal choice,” and manufacture doubt through sponsored research and scientific events. The authors conclude that “a unified global response to UPFs should directly confront corporate power… and disrupt the ultra-processed business model.”

The Lancet’s conclusion is unambiguous:

“A unified global response to UPFs should directly confront corporate power… and disrupt the ultra-processed business model.”

The message is unmistakable. Confront UPFs as was done for tobacco because they operate using the same machinery of influence, obstruction, and profit-driven harm. These arguments naturally intersect with MAHA’s own priorities and political positioning.

A MAHA Strategic Moment?

There is strong alignment between the Lancet’s authors and MAHA in the belief that UPFs dominate because of corporate engineering, not consumer failure, a systemic problem rather than one of “personal responsibility.” With this perspective, policy should target systems by

- restricting marketing and lobbying

- limiting corporate political and scientific activity

- targeting the industrial processes themselves (additives, emulsifiers, sweeteners, etc.)

The Lancet recommends front-of-package warning labels, UPF taxes, school-based restrictions, and bans on marketing to children—policies squarely aligned with MAHA’s agenda. Secretary Kennedy’s forthcoming report will likely reference this work. Yet an ironic tension remains: MAHA’s call for assertive regulation may clash with an Administration that favors voluntary corporate commitments and incentive-based approaches. This tension raises broader questions about how far the Administration is willing to go in confronting corporate influence.

MAHA wants definitive actions; the Administration desires voluntary corporate commitments; MAHA wants hard laws to replace loophole regulations; the Administration prefers partnerships and incentives. MAHA, if it is to achieve any of its goals, must remain a critique of corporate behavior within capitalism; the Lancet explicitly frames UPFs as a capitalism-driven system failure [2].

The current Administration may not be as willing to confront corporate power as MAHA hopes, particularly on issues involving labor, SNAP, or school nutrition programs. Whether forthcoming proposals will aim merely to contain UPFs or to eliminate them—as the Lancet suggests—remains uncertain. The answer will shape not only regulatory strategy but also how the public understands UPFs as a health and policy issue.

[1] Interestingly, population-wide risk exposure from infectious diseases, treatable with vaccination, does not seem to require the same broad regulatory strokes – a scientific and intellectual disconnect.

[2] Students of history will note that the two significant impacts of socialism on nutrition include forced collectivization, grain requisitioning, agricultural disruption, and state policies. In Russia, the extreme calorie deprivation and mass starvation led to 5 to 8 million deaths, especially in Ukraine, where almost 50% of children under age 10 died. China’s Great Leap Forward resulted in 15 to 30 million deaths due to severe chronic hunger, protein-energy malnutrition, and widespread micronutrient deficiencies.

Source: Ultra-processed foods and human health: the main thesis and the evidence Lancet DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01565-X