Bike riding, either for pleasure or as a way to commute to and from work, continues to reach new heights in popularity. Cities and municipalities all over America are reconfiguring streets and roadways to accommodate existing riders, and to encourage non-riders to climb aboard to improve their fitness with added physical activity.

But given that cycling-related trips to hospitals and emergency departments across the country have increased dramatically, is it a fair question to ask:

Are the steep rise in accidents, and the billions of dollars in annual medical expenses and costs associated with them, worth this push towards expanded two-wheeled transportation?

This observation comes to the fore in the wake of a recent study of a 17-year period published in the journal Injury Prevention which stated that, "Each year, the total costs associated with non-fatal adult bicycle trauma increased by an average of $789 million," and that "Medical costs increased by 137% from $885 million in 1997 to $2.1 billion in 2013."

Meanwhile, the "number of adult cycling injuries increased by approximately 6,500 annually," and the authors added, "Over the last 15 years in the USA, the incidence of hospital admissions due to bicycle crashes increased by 120%."

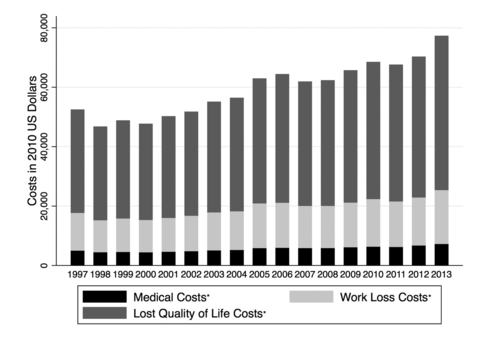

Since medical costs and emergency transportation expenses alone don't tell the whole story of the total price tag of these accidents, other expenses were factored in, like the cost of missed work, rehab and physical therapy, and quality-of-life costs. Those are calculated using data from jury verdicts stemming from injuries to bicycle victims. The adjacent chart shows the total average cost per case – excluding inflation – of non-fatal bike injuries in the U.S. (credit: study's authors Thomas W. Gaither, et al).

Since medical costs and emergency transportation expenses alone don't tell the whole story of the total price tag of these accidents, other expenses were factored in, like the cost of missed work, rehab and physical therapy, and quality-of-life costs. Those are calculated using data from jury verdicts stemming from injuries to bicycle victims. The adjacent chart shows the total average cost per case – excluding inflation – of non-fatal bike injuries in the U.S. (credit: study's authors Thomas W. Gaither, et al).

Researchers studied adult bicycle injuries from 1997 to 2013, utilizing non-fatal data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System and fatal incidence data from the National Vital Statistics System from 1999-2013.

One of their primary findings was that, "Costs associated with adult bicycle crashes exceeded $24 billion in 2013," the authors wrote, which is "approximately double the medical and indirect costs of occupational injuries in the USA."

In other words, as a nation we basically are spending twice as much money getting injured on the way to work then we are getting hurt while actually at work.

One main reason why the costs have risen so dramatically is because since so many more people are riding as a means of transportation, more and more bike accidents involve collisions with motor vehicles. That's compared to "non-street" incidents occurring in more forgiving environs, like parks and wooded areas.

In 2014, 67 percent of injuries took place on a street; in 1997, only 46 percent did. These street accidents are also usually more serious, since they're occurring at higher speeds.

"Street crashes represent an increasing proportion of total costs compared with non-street incidents. These crashes often involve motor vehicles, which increase velocity of crash impact and consequently injury severity," the study reports. "Streets might also predispose to more injuries due to the coexisting environment with urban areas, increased population density or the presence of more unyielding street furniture," like parking meters, anchored garbage cans, newspapers boxes and street lamps.

Another primary finding of the study was demographic in nature. The researchers learned that as injury-related costs soared, so have the number of bike riders aged 45 and up. "In 2013, 53.9% of total costs were due to riders 45 and older," they wrote, "up from 26.0% in 1997."

In addition, in the study's final year, male riders were involved in more than three out of four accidents (77%).

While we consider the rising costs and risks involved in pushing for more bike riding in America, it might be wise for urban planners to focus more intently on injury prevention methods that can be incorporated into overall safety awareness campaigns, and if possible, the streetscape itself.