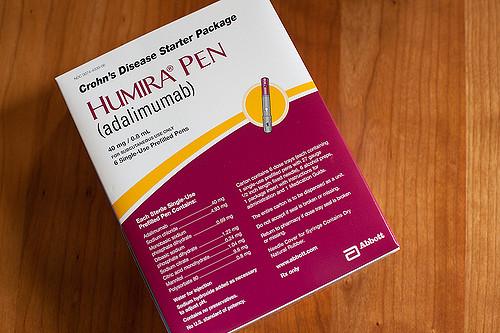

Humira is the world’s best-selling prescription drug, and today it loses its patent protection, at least in the EU. Humira is the trade name for adalimumab, (easy for you to say), that was initially approved for rheumatoid arthritis but has gone on to have indications in a variety of diseases. It was not the first biologic, a term used to describe complex medications rather than small molecule compounds like furosemide (Lasix) or atorvastatin (Lipitor); that honor goes to insulin. But it has been the most successful, with sales for its manufacturer, AbbVie, of around $20 billion worldwide annually. Today, the door opens for biosimilars, the generics of the biologic’s world, and they have been waiting in the wings.

To understand the differences between a biologic and its biosimilar take a look at what I wrote here. But here is the quick summary for those late to the party. A biosimilar

- Must have an identical basic structure as the biologic.

- Must have the same pharmacokinetics.

- A biosimilar’s immunogenicity can be no greater than its biologic equivalent.

- A biosimilar must be shown in a study to be clinically equivalent to the biologic for one of the diseases it will be treating. [1]

Many of their competitors are lined up to take advantage. Mylan, you remember them from their pricing of Epi-Pens, has been granted a license to “commercialize” Hulio, a biosimilar made by

Kyowa Kirin Biologics, a part of Fujifilm (and you thought they only made film). And the list includes four other firms, already with regulatory approval for their Humira “wannabes.” The EU is a $4 billion market and accounts for two-thirds of AbbVie’s revenue. This is a big deal and a real challenge for AbbVie and healthcare systems.

When Humira was introduced, it cost $19,000/annually. Its current cost is $38,000/annually in the US. The price in Britain is about half of that, and in Switzerland, the cost is a third of what we pay here in the States. So while the EU market is the latest battleground it is merely the foreshadowing of the fight yet to come when Humira’s US protection ends; its patents ended in 2016. But AbbVie protected their market using both a stick and carrot. The stick involves obtaining over 100 patents on different components of the manufacturing process making it very difficult to create a biosimilar without infringing and subsequently paying, AbbVie. They have patents on methods of treatment, drug formulation, and manufacturing. The end effect is almost doubling their period of exclusivity. A German company, Boehringer Ingelheim, has a biosimilar approved in the EU and set to go, but will not participate in Tuesday’s celebration because it has been accused of infringing upon 74 of Humira’s patents.

For those companies that are willing to give AbbVie a bit more exclusivity, say till 2023, they have proffered the carrot of out-of-court settlements, another way of describing payments to stay out of the market or face litigation. Those companies include Amgen, who was initially threatened with patent infringement until they saw the light and led the way on settlements; Biogen and a joint venture with Samsung (Yes, I thought they only made electronics too) Samsung Bioepis, both of whom will be marketing in the EU now, have also agreed to wait until 2023 in the US.

For healthcare systems, the expiration of Humira’s patent is welcome news. Biologics are budget breakers, so the introduction of lower-priced alternatives is key in controlling costs. The EU is ahead of the US in the adoption of biosimilars, the UK’s National Health Service, always in the red, has stated: “Our aim is that at least 90 percent of new patients will be prescribed the best value biological medicine within three months of launch of a biosimilar medicine, and at least 80 percent of existing patients within 12 months, or sooner if possible.” They have already moved 80% of their patients to They will offer more than one alternative biosimilar and move patients to the “best value” medications. Now, of course, how one determines value in another question entirely. Many patients have been through a number of medications and are reluctant to stop what is working for them to save money, frequently money coming from insurance, not out of pocket; you know, if it’s not broke, don’t fix it. So it should be no surprise that AbbVie’s rebuttal is that, “patients who are stable on their existing biologic therapy should not be switched to another product for non-medical reasons.”

Finally, in another attempt to enter the biosimilar market, Pfizer is suing J&J over their biologic, Remicade – used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Their claim that J&J used its market advantage to keep their less expensive biosimilar off insurance company’s drug formularies by offering discounts and incentives. An anti-trust problem that is awaiting trial

One last thought, the discount from biosimilars is not as great as those for generics from those previously mentioned small molecule drugs like Lasix and Lipitor. Generics usually take about three years to successfully copy and get approval; biosimilars have taken up to nine years to accomplish copying and authorization at costs that make generic development chump change, at least to Big Pharma. So while there will be savings in the EU, they will help but not solve healthcare’s financial difficulties.

[1] This has led to a discussion in the US over whether a biosimilar being approved for one indication should allow blanket approval for all the indications of the original biologic without further studies.