Food packaging comes with lots of labels; the government mandated nutritional contents, perhaps some form of “Healthy Choice” certification, and those front-of-the package (FOP) snippets designed by marketing. An intriguing study describes a new way to view how we make our food choices and was written by real experts, marketers.

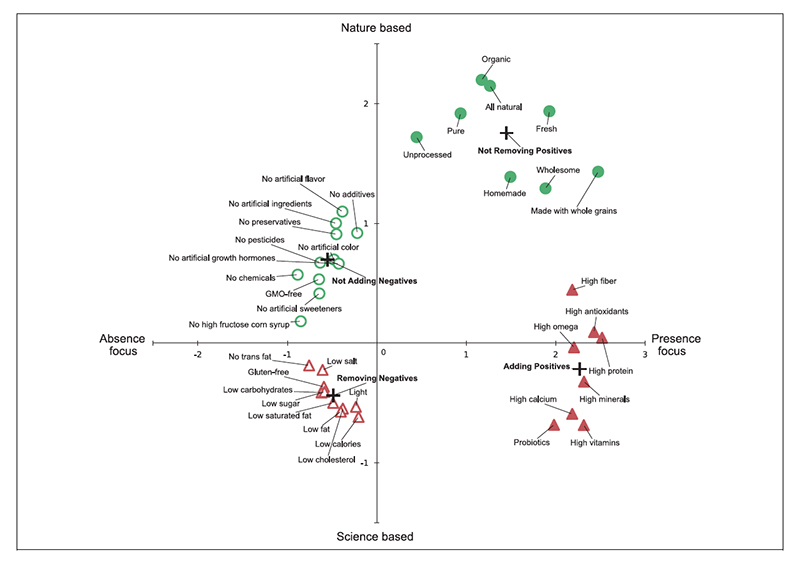

The researchers developed a framework describing variations in FOP claims. Their model considered two variables, whether a food claim focuses on positive or negative attributes, and whether these claims have a natural or scientific basis. For example,

- Science and presence focus – “high in vitamins” or “probiotics

- Science and absence focus – “low fat” or “light.”

- Nature and presence focus – “made with whole grains” or “unprocessed.”

- Nature and absence focus – “no artificial colors” or “no additives.”

The researchers validated their model winnowing 107 food claims on US products down to 37 that were both familiar to consumers, and classified into these four groupings irrespective of gender, age, ethnicity, income or education. The classification was unchanged by body mass index, and by a participant’s interest or knowledge of nutritional information. The chart shows the breakdown.

The researchers limited their study to breakfast cereals, 633 products in all, coupling the product claim to the nutritional value of the product. [1] 72% of cereals have some health or nutritional claim. While most cereals make only one claim, some cereals have multiple claims but rarely do invoke more than one of the groupings. Most importantly they found that the type of claim “is completely uncorrelated with the actual nutritional quality of the food…”

While the cynical amongst us, would find that last finding unsurprising, the authors wanted to see if consumers recognized this discrepancy and undertook a series of studies employing on-line surveys using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, where participants receive a small fee for completing a questionnaire. Prior studies have shown that most consumers when purchasing food are looking for taste, but others seek a health benefit or a dieting benefit.

Using four claims from each cluster, consumers were asked whether upon seeing these cereal claims they would believe the cereals were “healthy,” or “tasty,” or “would help them lose weight.” In a second study, they asked women, age 18 to 64, still the primary purchaser of foods, to make a choice of cereal and milk for “teenage guests.” They were also told whether the guests “care about healthy eating,” “trying to lose weight,” or to pick something their guests “would enjoy.” In addition to claims from the four clusters, they included cereal and milk without any claims.

It should be no surprise that the FOP claims acted as a means of framing benefits; after all, that is their intent. Inferences about health, taste, and dieting differed based on the claims and purchasers were more motivated when a claim was made; no one was rushing to buy cereal or milk without an expressed added value.

- The discrepancy between a cereal’s nutritional value and claims persisted.

- Healthiness was more often inferred from what was present, rather than what was absent and from a science-based rather than nature-based claim.

- Tastiness was also more often inferred from what was present than what was absent - removing elements is perceived as more “taste degrading.” But nature-based claims were associated with tastier foods, than science-based claims

- Dieting was the outlier, what was absent, not present was the key, and science knew better what to remove than Mother Nature.

The marketers demonstrate that their claims make a difference, increasing the likelihood that a particular cereal will be chosen and that a claim’s effectiveness varies with the intent of the purchaser. Those front-of-the-package snippets are far more effective in driving consumer choice than all those back-of-the-package nutritional labels. And if that is the case, then perhaps regulators should spend more time thinking about how we understand or misunderstand the snippets than the labeling.

In surveying consumers, most food purchasers are driven by taste. The two claims driving purchases for taste in this study were “made with whole grains,” and “all natural.” We agree with the Center for Science in the Public Interest in singling out those two claims as particularly misleading in the case of whole grains and without any meaning at all for the phrase “all natural.” So much for all those nutritional labels, ignored in favor of a phrase on the front of the package.

[1] Nutritional quality was scored using a measuring “instrument” designed for the British Food Standard Agency, allocating positive points for sugars, saturated fatty acids, and sodium; and negative points for fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, fiber, and proteins. -15 is the most nutritional, 40 the least.

Source: Healthy through Presence or Absence, Nature or Science? A Framework for Understanding Front-of-the-Package Food Claims Journal of Public Policy and Marketing DOI: 10.1177/0743915618824332