Genome-Wide Association Studies, GWAS, look at the genomic milieu, but the presence or absence of a gene rarely tells the whole story. Genes, need to be transcribed, and ultimately metabolic products are created. Each of these inter-related levels has additional influencers and feedback mechanisms. Genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analysis are all currently active areas of investigation in the field of “omics.”

Taking a page from Dracula, studies in which older and younger mice have their circulations surgically connected, termed parabiosis, demonstrate that younger mice age more quickly, while those older mice are “rejuvenated.” While that finding has prompted charlatans to offer the blood of young donors for sale, it has prompted serious research on how and which of the multitude of proteins within our blood influence aging. We are just at the beginning of these investigations, there are no causal factors identified, and there will be no pills or treatment coming in the short term. A new report from Nature Medicine reports from the frontier on how the protein composition of our blood, a fluid that “contains proteins from nearly every cell and tissue,” changes with age.

The researchers utilized blood samples from roughly 4300 individuals age 18 to 95 and identified approximately 1400 proteins whose concentrations changed over time. Phenotypically, we know that men age differently than women; a metabolic basis for that observation may come from the fact that of those 1400 “aging” proteins, almost two-thirds of them were significantly different in men versus women.

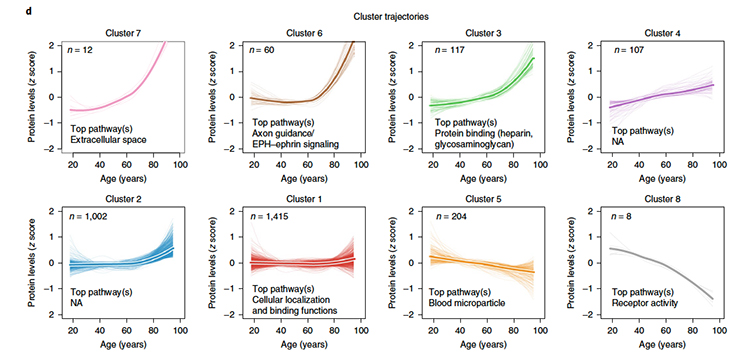

It is a combinatorial nightmare to consider how each of these 1400 proteins interacts, so the researchers grouped them to reduce the complexity of analysis. As you might expect, the pattern of change in the proteins, their trajectory varied over time, some linear, others exponential, but most in a non-linear manner. Those trajectories identified 8 clusters represented in this graphic.

The researchers poetically described the aggregate pattern created by these varying trajectories as “undulating;” and identified three “crests” at age 34, 60, and 78. And while there was some overlap, each of these crests was mostly unique compositions of proteins.

“Altogether, these results showed that aging is a dynamic, non-linear process characterized by waves of changes in plasma proteins that reflect complex shifts in biological processes.”

Many of the proteins identified were part of signaling pathways, proteins carrying information from tissue to tissue throughout the body. Other proteins represented additional key biologic pathways with little overlap, a finding consistent with the idea that aging reflects the loss of the resilience that redundancy provides.

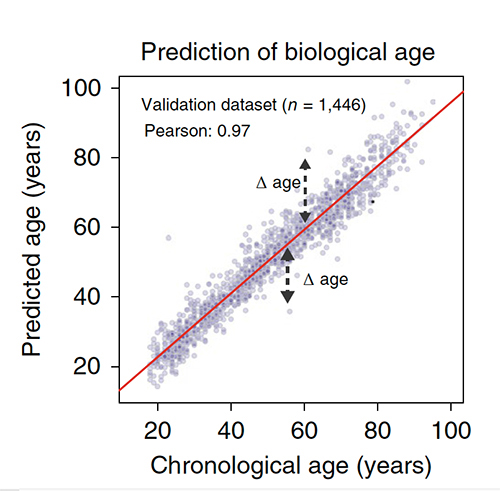

The researchers point out that the changing protein profile, the proteomics, are at this juncture best thought of as biomarkers, not causal agents. It is just too early in the investigation to be more confident in their roles. There were able to create a proteomic clock to predict one’s age with a great deal of accuracy. While they report that patients whose age was underestimated did better on cognitive and physical tests than their peers, they made no mention of the findings for those individuals whose age was overestimated.

The researchers point out that the changing protein profile, the proteomics, are at this juncture best thought of as biomarkers, not causal agents. It is just too early in the investigation to be more confident in their roles. There were able to create a proteomic clock to predict one’s age with a great deal of accuracy. While they report that patients whose age was underestimated did better on cognitive and physical tests than their peers, they made no mention of the findings for those individuals whose age was overestimated.

Source: Undulating changes in human plasma proteome profiles across the lifespan Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-019-0673-2