This article was originally published at Geopolitical Futures. The original is here.

All human institutions are political. This follows naturally from Aristotle’s observation that “man is by nature a political animal.” If one wishes to rise to the very top of one’s field, it is not sufficient to be competent. Instead, one must also be diplomatic, savvy and – when the time calls for it – brutal. Even the Pope had to step on a few miters on his way to the Vatican.

The trouble with politics, though, is that it requires credibility. It is difficult to balance competing demands, which inevitably engender disappointment and resentment and opens oneself to the vulnerability of making a wrong decision. To co-opt a quote dubiously attributed to Abraham Lincoln, “You can please all of the people some of the time, and you can please some of the people all of the time; but you can’t please all the people all the time.”

For many institutions – particularly those in government – the struggle between maintaining credibility and meeting public demands is a familiar one. Others, like the medical establishment, have less experience with this concept. The biomedical community has often enjoyed the luxury of working in relative isolation the exigencies of politics. This shield of semi-privacy enabled greater trust in expertise; a smaller spotlight means a greater mystique and less criticism. But today, that is not the case. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the practice of medicine and public health to the fundamental political dilemma of balancing competing demands.

To observe this struggle playing out in biomedical institutions, one need not look further than two different leaders who find themselves at the forefront of medical and now political debates: Dr. Tedros Adhanom, director-general of the World Health Organization, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the de facto spokesperson for America’s COVID-19 response.

Tedros is already in hot water. His political instincts, which allowed him to climb atop the world’s most prestigious health organization, did not adequately prepare him to face the coronavirus as a global pandemic. The WHO was complicit in China’s early cover-up of the virus, including by suppressing vital information from Taiwan on human-to-human transmission. Once the outbreak was public, Tedros was China’s most prominent supporter, effusively praising the nation, particularly for how quickly it sequenced the genome and offered it up to the global community. He also highlighted China’s effectiveness in bringing the outbreak under control. That China was able to implement broad and powerful measures to slow the outbreak is indeed true. But China also silenced whistleblowers, waged a massive disinformation campaign, forcibly dragged sick, crying citizens out of their homes and welded the doors shut on apartment buildings.

As it often turns out, politics – not an unbiased public health assessment – was the likely motivation for Tedros’ behavior. Though the general public may not be used to thinking about public health agencies as political entities, countries often seek influence in international institutions to gain political leverage. In 2017, Tedros became the head of WHO after China gave him its support. Thus, he owed his benefactor a favor and had to return it when called upon. In the process, he has harmed the WHO’s reputation, earning it the label of “China’s coronavirus accomplice,” which could threaten the organization’s political clout and funding sources, ultimately hurting its ability to carry out important work. Worse, several U.S. senators are now calling for Tedros’ head. They might get it, too, since the United States is the largest funder of the WHO. Money talks, and this global medical institution now finds itself in the middle of a geopolitical spat between the United States and China.

While Fauci isn’t likely to face that level of political scrutiny, he won’t come out of this unscathed. (President Donald Trump has already retweeted a post with a #FireFauci hashtag.) He is widely respected for many reasons, one of which is that he has headed the NIAID since 1984. He is accomplished and successful, but he is now facing perhaps the hardest job of his career: He has the precarious task of simultaneously serving as a public-facing proxy for the U.S. president, representing the biomedical community, and telling the scientific truth to the best of his ability. These can be conflicting roles.

A politician approaches the situation fundamentally differently from a physician. The president needs to protect both public health and the economy, and pursuing one could put the other at greater risk. Accompanying all of this is a political agenda with an eye to securing re-election and a desired presidential legacy.

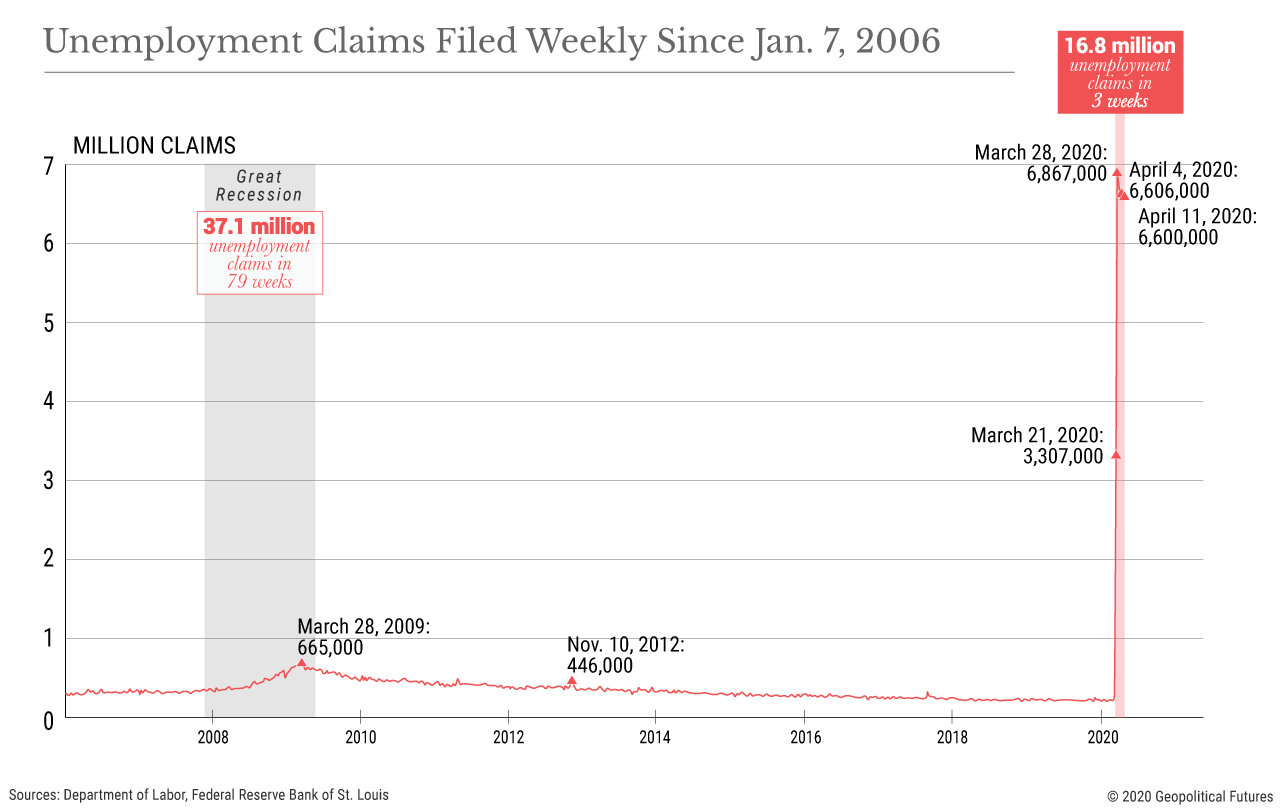

However, the biomedical community, led largely by academia, has decided that public health is worth prioritizing over the economy. This is unsurprising given that medical institutions are data-driven and feel little need to be responsive to public opinion. Applied to all of society, the Hippocratic Oath, which demands, “First, do no harm,” means pushing for health-centric measures (like more conservative lockdowns) in an effort to minimize casualties and deaths as much as possible. At the present time, American public sentiment aligns with the biomedical community on moral grounds and supports the extensive social and physical restrictions that aid its fatality prevention strategy. The prevailing belief can be summarized as, “Economies can be revived; dead bodies cannot be.” Yet, while the United States has been in lockdown, more than 16 million people have filed for unemployment in just the past three weeks. The question about a coming recession is not “if” but “how bad.”

These are the opposing forces squeezing Fauci. Still, he has a third consideration: scientific truth. And the truth is muddled, to put it mildly. For instance, a recent review published in “The Lancet” concluded that school closings are not very effective in slowing the spread of the coronavirus. But it would be political suicide for Fauci to announce that schools should reopen – the biomedical community would revolt against him – and Homo politicus is not suicidal. Fauci has therefore thrown his support behind the biomedical community’s demand for a national lockdown of indefinite length. And, for good measure, he says people should never shake hands again.

What Fauci and the biomedical community likely will soon discover, however, is a growing divide in public opinion over the enacted measures because they are not affecting people in the same way. Some have lost their jobs while others are working overtime. Similarly, people are experiencing physical isolation to varying degrees across the country. Humans are social animals, and we cannot stand living in isolation and boredom. Small signs of civil disobedience in the rejection of lockdown measures have already begun to appear, such as hikers trespassing in Oregon’s recreational areas and throwing signs off the road. As people’s bank accounts run dry, Fauci and the biomedical community will find themselves between a rock and a hard place. The policy of “do anything to stop the virus” is going to meet the cold, hard reality of an angry citizenry.

With about three-fourths of Americans under lockdown, the unintended consequences will be vast. There has been a notable decrease in the number of heart attack and stroke patients arriving at hospitals, presumably because they are afraid of catching the coronavirus or of not finding a hospital bed. As the economy spirals downward, we can also expect an increase in mental health crises, domestic violence and suicides. While lockdown supporters say that to have a functioning economy, we must have good public health, the reverse is also true: To have good public health, we must have a functioning economy.

The doctors, nurses and medical staff on the frontlines of the pandemic are true heroes. The public largely believes the same about the biomedical community’s leadership, as well. But, the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic have forced Tedros, Fauci and the biomedical community into the political challenge of maintaining credibility while responding to competing demands. They have little experience to rely on and are gambling that people’s affection for and trust in doctors will give them the authority to prescribe policies that will upend society for the foreseeable future. However, when the economy collapses – and especially if the virus keeps spreading anyway – public sentiment will change quickly and drastically. Americans’ trust in the medical establishment may be shaken. Like ventilators, the national supply of goodwill isn’t unlimited.

© 2020 Geopolitical Futures. Republished with permission.