“Blindness separates us from things but deafness separates us from people.”

Helen Keller

The study used data collected as part of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study, with almost 16,000 participants in four US areas. Four thousand were available for in-person visits in 2016-2017; after exclusions for missing data, the study group numbered 3,000.

Audiometry testing categorized individuals as having normal, mildly, moderately, or severely impaired hearing. Outcomes included balance, gait speed, and chair stands – a measure of strength and balance.

Mean age 79, 58% women, nearly 80% White. As expected from the introduction, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% moderate, and 4% severe, and the remaining 33% had normal hearing.

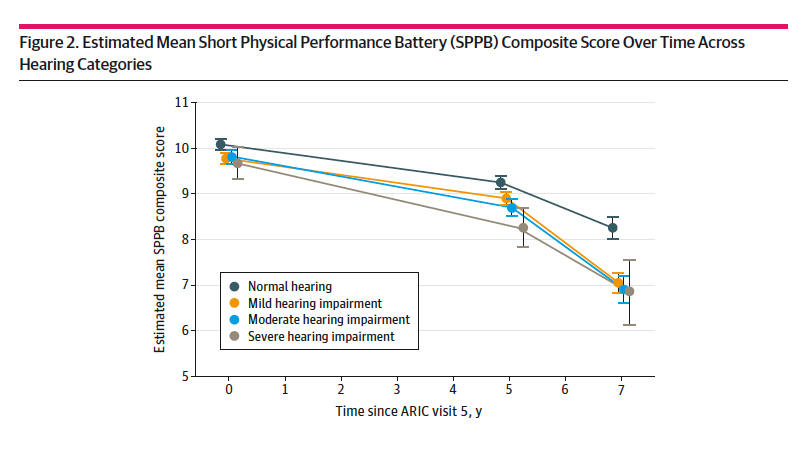

- Increasing hearing impairment was primarily associated with decreasing gait speed.

- When broken into categories of hearing loss, balance was impaired in a step-wise fashion.

- The decreasing gait speed also diminished the distances these participants could walk during the “timed” portion of their evaluation.

- The rate at which these physical abilities declined increased with the degree of hearing impairment.

Overall, the losses of physical function for those with severe hearing loss were clinically significant – they were increasingly dependent despite being community-dwelling. (Science’s way of describing free-range humans). Why would our hearing impact our walking?

The most bioplausible, intuitive reason is an associated impairment of balance, which is a vital role of our ears, and only indirectly measured by these tests. You cannot move quickly, let alone safely, through your environment without balance and acoustic feedback, however subconscious that might be. That is a good explanation of why chair standing, which evaluates strength more than balance, remains more intact. The researchers note in their sensitivity analysis that there was no correlation between grip-strength, a pure measure of strength, and hearing loss; impaired balance may well be the “unknown known.” (RIP Donald Rumsfeld)

Another intriguing finding was the reduction in walking endurance, a cardiovascular function. It remains unclear whether hearing is, therefore, a “biomarker” of cardiovascular disease or that hearing impairment reduces your social world – you simply get out and about less and therefore exert yourself less, reducing your “conditioning.” This is a significant concern because a diminishing life-space, a term for the usual places we inhabit over the day, becomes an increasing self-fulfilling prophecy. Contraction of our life-space moves us from walking the neighborhood to remaining in the house to staying in the living room and bedroom, to remaining in bed.

As our population ages, as the boomers turn grey, more money will be diverted into assisted living. Perhaps hearing aids will alter the effects of hearing loss on physical function.

Currently, the national average monthly cost for assisted living is about $4,100, roughly half the monthly nursing home care cost. A good pair of hearing aids costs less than one month of assisted living. It would be nice to see whether hearing aids make a financial difference; we already know they make a difference in the quality of one’s life.

The study did not look specifically at that issue, but hearing aids did not seem to alter the decline. That “conclusion” is entangled; hearing aids were more frequent among those with higher income, which was in itself associated with less physical impairment. Studying the effect of hearing aids on slowing the decline in our functional abilities would be a boon to increasing numbers of our citizens. It would also help influence how our tax dollars are spent. Medicare does not currently cover hearing aids; Medicare Advantage programs do. A directed study could provide evidence-based science for regulatory policy.

Source: Association of Age-Related Hearing Impairment With Physical Functioning Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in the US JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13742