Bacteria cause most foodborne illnesses, particularly E. coli, Salmonella, or Listeria. The CDC estimates that about 48 million Americans get sick each year, 128,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die from foodborne diseases. The government has tried to respond to these outbreaks by attacking the problem at its source – the farms producing the food.

Background

Almost a quarter of foodborne disease outbreaks in the US (2006-2014) were caused by fresh produce.

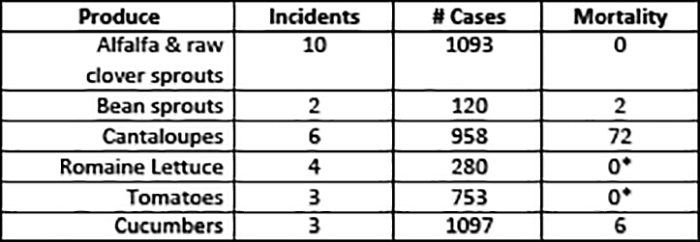

These outbreaks have occurred from consuming all types of fruits and vegetables. The following table lists some of the most significant disease outbreaks investigated by the CDC and found to be caused by fresh produce (2005 – 2019). Note - This is not a complete list because many episodes were never investigated by the CDC or were investigated and the cause was never determined.

*Some information was not reported

What’s the Story with Sprouts?

If you wonder why you rarely see sprouts anymore in stores or restaurants, sprouts are at the top of the list of produce causing disease outbreaks. The two worst E. coli outbreaks in the world were caused by raw sprouts: an outbreak in Germany in 2011 killed 53 and sickened 3,950 people, and an outbreak in Japan in 1996 killed 12 and sickened 9,441 people. There have been at least 12 outbreaks in the US since 2005, sickening over a thousand people and killing two people.

The reason why there have been so many disease outbreaks associated with raw sprouts is that sprouts are simply seeds that have just begun to grow. They are easily contaminated in the field, and once the bacteria are on the seed, they can survive in a dormant state for weeks. When harvested, they are put together in hoppers, and bacteria on one seed can be spread to millions of clean seeds.

Government Response

In 2015, to deal with illnesses caused by fruits and vegetables, the FDA finalized the Produce Safety Regulation, establishing requirements for “covered produce,” i.e., fruits or vegetables in an unprocessed state and are usually consumed raw.

The FDA includes a long list of covered produce, including most nuts, mushrooms, sprouts, herbs, spinach, apples, peaches, pears, and watermelons. Produce that is not included because they are rarely consumed raw include beans, eggplants, dates, sweet potatoes, beets, and pumpkins. However, some of these are real head-scratchers; for example, peanuts and pecans are not included as covered produce (doesn’t everyone eat these raw?), while summer squash is included (does anyone eat raw squash?).

The most likely way for pre-harvest produce contamination to occur is through contaminated soil or water. Agricultural water is defined as any water used to grow fresh produce and sustain livestock. It is used for irrigation, pesticide and fertilizer application, crop cooling, and frost control. Water becomes contaminated when human or animal feces find their way into water sources used for irrigation or other farm uses, usually from surface water, such as ponds, streams, rivers, or dams near the farm. Farms also use groundwater (wells) for irrigation, but since the underground soil naturally filters the water, it is much less likely to be contaminated than surface water.

The most likely way for pre-harvest produce contamination to occur is through contaminated soil or water. Agricultural water is defined as any water used to grow fresh produce and sustain livestock. It is used for irrigation, pesticide and fertilizer application, crop cooling, and frost control. Water becomes contaminated when human or animal feces find their way into water sources used for irrigation or other farm uses, usually from surface water, such as ponds, streams, rivers, or dams near the farm. Farms also use groundwater (wells) for irrigation, but since the underground soil naturally filters the water, it is much less likely to be contaminated than surface water.

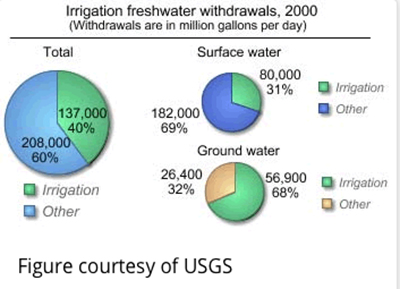

Most people don’t recognize how much of our water goes to farming. As shown in the chart below, agricultural water used for irrigation represented about 40% of total water use in the US (2000). [1]

Most people don’t recognize how much of our water goes to farming. As shown in the chart below, agricultural water used for irrigation represented about 40% of total water use in the US (2000). [1]

“Agricultural water must be safe and adequate for its intended use.”

In 2015, the FDA set an extremely complicated and technically complex rule for farmers, requiring that they meet a required level of bacteria (E. coli) in 20 samples of untreated surface water or four samples of untreated groundwater with mean and statistical threshold values set at a different, specified level of bacteria.

Most of today’s farms are large and are big business. But some smaller farms are exempt [2]. Farms may also be exempt if they only harvest produce used for personal or on-site consumption or use commercial processing that adequately reduces the presence of microorganisms.

Farmers Fighting the Government

If you found the above rules challenging to understand, imagine how the farmers reacted! After two years of “outreach and education,” the FDA’s feedback from farmers was that the rules were:

- Inflexible by proposing a “one-size-fits-all approach.”

- Too complicated to understand.

- Difficult to implement because farms with multiple agricultural water sources must establish individual microbial water quality profiles for each water source.

On December 6, 2021, the FDA did something not often seen with government regulations; they scrapped their initial approach and proposed a brand-new alternative.

They proposed replacing the previous requirements with a new condition - that farms prepare written agricultural water assessments at least once a year. This applies to all covered produce, except sprouts that still have to meet the 2015 rules.

The agricultural water assessments must contain:

- The location, nature, and type of water source and distribution system

- The degree to which the agricultural water systems are protected from possible sources of contamination by other users of the same water systems and by adjacent and nearby land uses

- Agricultural water practices, including the type of irrigation method and the time interval between the last application of agricultural water and harvest of the produce

- Crop characteristics

- Environmental conditions, including the frequency of heavy rain, air temperature, and sun exposure

Are Agricultural Water Assessments the Answer?

Agricultural water assessments appear to be an academic approach and a gold mine for environmental consultants. Yes, a lengthy assessment of all the possible sources of contamination may result in finding and preventing problems on the farm. But this solution may also result in the following unintended consequences:

- Raising prices on produce: These assessments are lengthy analyses that will probably require hiring environmental consultants, adding to the cost of the produce.

- Reduction in produce consumption: Increasing the price of produce will result in reduced consumption, particularly in lower-income Americans. This runs counter to the USDA’s goal of increasing fruit and vegetable consumption for all Americans.

- Put small and medium-sized farms out of business: Although the rule exempts very small farms, the sales cut-off is extremely low ($25,000 over three years). The added cost of doing these assessments could be significant for small and medium-sized farms that do not have the margins for added costs.

- Switching from untreated water to treated water: Since farms only have to conduct water assessments if they use untreated water, this may cause some farms to switch to treated water. In this age of water scarcity, more farms' use of treated water could lead to further shortages of water for drinking water purposes.

It needs to be remembered that no farm, no matter the size, wants to be the source of a foodborne illness; it not only could hurt their reputation but put them permanently out of business. I applaud the FDA’s willingness to propose an alternative to their initial approach. If the FDA does go forward with finalizing this rule, they should actively monitor the results and see if this approach does lead to a reduction in foodborne disease outbreaks. This should not be a report that ends up sitting on a shelf someplace in a government office.

I believe that a better solution would be for the FDA to work with the USDA Agricultural Extension Service to try and solve this problem. There are approximately 2,900 Extension Service local offices across the US with a long history of working with farmers to help solve their problems.

The FDA could create a simple checklist where farmers check off any potential source of water contamination that may be present on their property. The results could be forwarded to the Extension Service office nearest the farms so that they could work collaboratively with the farmers to try and prevent the contamination. Such a collaborative approach seems to me to be much more productive than requiring agricultural water assessments, which will more than likely sit on shelves gathering dust (and potential pathogens?) and not solve the problem.

[1] The amount of water withdrawn for irrigation in the US has remained relatively steady, reported at 42% in 2015. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-practices-management/irrigation-wat...

[2] They are exempt if they have an average annual value of produce sold during the previous 3-year period of $25,000 or less or have total food (not just produce) sales averaging less than $500,000 per year during the past three years.