Gun violence restraining orders (GVRO), the legal term for red flag laws, allow the courts to “temporarily prohibit individuals from possessing and purchasing firearms and ammunition during periods of heightened risk of self- or other-directed harm.” Along with 18 other states and the District of Columbia, California has instituted a version of these laws – the study reports on the first three years of California’s experience.

GVRO’s come in three forms,

- an emergency order, used by police, lasting 21 days

- a temporary order, used by all, again lasting 21 days, which leads to

- a hearing, when the court can issue an order lasting one year

The subject must surrender their guns and ammunition to the police or a licensed firearms dealer within 24 hours. The overall dataset of the study were cases filed between 2016 and 2018; 413 cases. Of those, 218 were court-ordered and contained information on the circumstances of the GVRO. 95% of the remaining cases were emergency orders issued by police. The single-page documentation of these cases often failed to contain the information that the study wanted to gather. Can we all agree for the moment that it is doubtful that police capriciously took a weapon away from an individual?

GVRO respondents differed from California’s firearms owners and general population in several ways:

- They were younger (39 vs. 57) and more often male than firearms owners or the general population

- Blacks “constituted a larger proportion of respondents (10.0%) than firearm owners overall (4.4%).”

- Veteran respondents were two-fold greater than the general population, but only one-third of the gun-owning group.

The Details

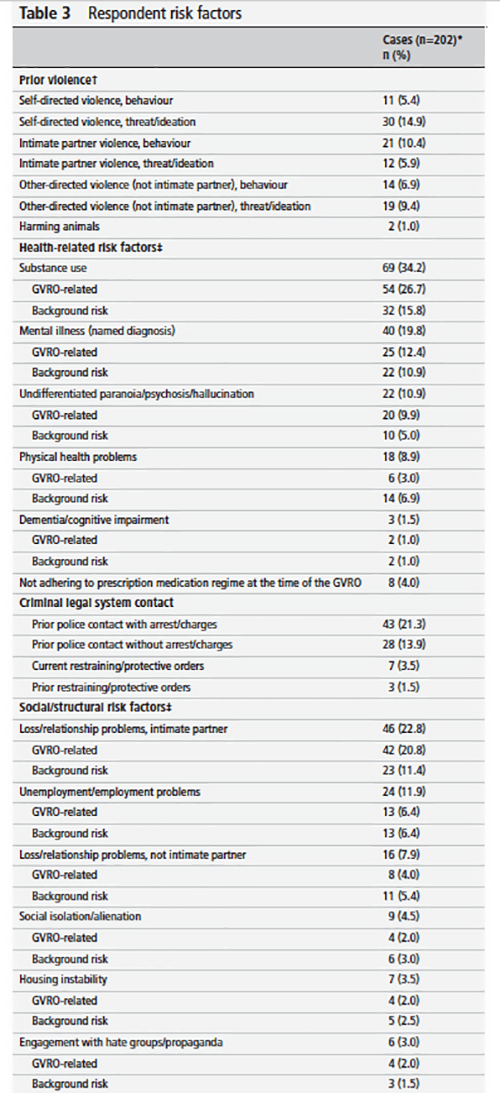

- Risk factors are detailed to the right

- 54% involved a threat to others, 15% danger of self-harm, and the remainder a threat to both self and others

- Of the “others,” 29% threatened intimate partners, 21% family members

- Slightly more threats were behavioral than verbal, with 33% involving “brandishing or using a firearm.”

- 25% involved a threatened “mass shooting.” Interestingly, all six cases involving minors were mass shooting threats, all directed at schools.

- 60% of the threats occurred in private residences, 25% in public venues.

- 85% of respondents owned the guns, in 4%, they were not the owners, and in 6%, ownership was unclear.

- Respondents owned a median of two guns.

- Handguns were removed In 85% of cases, rifles in 46%, and assault weapons in 30% of cases.

- In 12% of cases, no firearm was recovered.

- 33% were arrested on criminal charges, with 23% transported to the hospital and another 23% placed on an involuntary psychiatric hold.

- Police use of force [2] in these cases was roughly 5%

- 96.5 % of the petitioners were law enforcement officers, family petitioners for GVRO only 3.5%

- The courts issued prolonged GVRO was not sought in about 33% of cases; in those pursued, GVRO were issued in 85% of cases, the rest denied.

- 3 (2%) of respondents subsequently died, one by suicide, the proximate cause of his GVRO.

A summation

The California data shows more GVROs issued for harm to others than in other states where self-harm is more frequent. If you look at the risk factors, substance abuse and mental health issues are predominant. As the researchers suggest, perhaps greater coordination between mental health services and law enforcement would be helpful. The researchers raised concerns that the 33% arrest incidence on criminal charges was more significant than in other states. GVRO, a civil mechanism, might be used to target criminal behavior – shades of broken window theory. I would disagree, but I am open to other views.

They also pointed out that no weapon was recovered in 12% of cases, again somewhat higher than in other states. Whether this was due to police enforcement laxity or hidden or sold weapons is unknown. But without confiscation, GVRO seems to have no purpose. Finally, as the researchers and we note, the dataset is limited, and the percentages might change with more information regarding the emergency GVROs. My take is that red flag laws can work, they have gaps that need to be addressed, and they may reduce the most frequent forms of gun violence. What do you think?

[1] Bipartisan Senate Coalition Floats Expanded Background Checks, Red Flag Laws for Guns National Review.

[2] This included pointing a firearm at the respondent or using less than lethal force, e.g., a taser.

Source: Gun violence restraining orders in California, 2016– 2018: case details and respondent mortality Injury Prevention DOI: 10.1136/injuryprev-2022-044544