A quality-adjusted life year (QALY) is used as a generic measure of how disease impacts the quality and quantity of your life. A QALY ranges from 1 (perfect health) to 0 (death). This represents a range of what economists call “utility,” but we might call it our joie de vivre, the enjoyment of life. To calculate its value, you simply multiply that utility by the years you live in that condition.

While the 1-0 poles of QALY can be more or less objectively defined, those values in between are subjective. Being able to walk only a block is disabling for the mail carrier but may not be an issue at all for the couch potato. It is this subjective component that's problematic for many in disabled communities. For example, to those with no hearing loss, deafness may reduce the quality of one’s life by 25% or more. For members of the deaf community, it may not represent a quality issue at all. They would object that a QALY, determined by someone outside their community, may restrict their access to care or reduce the amount of payments made as legal redress for an injury.

Like any measure that seeks to adjust for two conditions simultaneously (length and quality of life, in this instance), it simplifies. That simplification is helpful in quantifying tradeoffs from a societal perspective but can fall short when considering the individual.

Health economics

From a societal perspective, the decision to purchase medications is often subject to a cost-utility analysis: is the benefit of the drug or procedure worth the price? Even with the lack of transparency regarding our healthcare costs, it is a relatively simple process of determining the cost of care. What is far harder to ascertain is the medication’s or procedure’s benefit. This is where QALY plays a role.

Consider hemophilia, a rare disease impacting about 20,000 individuals in the U.S. It's a treatable disease involving the replacement of blood products. According to the National Hemophilia Foundation:

“The average annual cost of clotting factor therapies for a person with severe hemophilia is roughly $300,000. Medical expenses for a person with severe hemophilia, the most common form of hemophilia, can be twice that. A person with an inhibitor (an immune response to replacement clotting factor) usually has expenses over a million dollars a year.”

The FDA has approved a gene therapy for one form of hemophilia involving a one-off infusion that costs $3,500,000 – making it the most expensive drug globally, at least for the moment. A rough calculation would say that if the gene infusion adds 12 years to your life, it pays for itself by reducing those annual costs for clotting factors. The same analysis using QALY might account for costs other than money, e.g. the time lost from work is often a favorite in these calculations. Additional external costs, such as transportation or the need to be hospitalized, may reduce your subjective quality of life and make that gene therapy an even better bargain.

Using QALY

Consider the following example. Let's begin with the benefits.

A patient has some disease that causes the person to rate their quality of life at 0.6. Medication can improve their situation, but not wholly, causing them to rate their quality of life at 0.8. Surgery will resolve the problem completely, producing a QALY of 1.

- Without treatment, their QALY over the next five years is 0.6 X 5 = 3.0 QALY

- With medication, over the same five-year period, it is 0.8 X 5 = 4.0 QALY, a gain of one QALY.

- Surgery would make the gain 2 QALY.

Now we can put some theoretical costs to those benefits. Medication costs $3,000 annually. Surgery is a one-time payment of $10,000. For treatment with medication, the cost for that one QALY gain is $3,000 x 5 = $15,000 for 1 QALY gained. For surgical management, the cost of that two QALY gain is $10,000 x 1 = $10,000/2 QALY = $5,000 for one QALY gained.

Surgery is the more economical option over five years, but if the patient was only to live an additional 18 months, that economic advantage would switch to medical management. The different valuations of cost and benefit from differing therapies are termed the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, or ICER. These are how QALYs are used in cost management.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence provides the UK with QALY estimates used by the National Health Service in allotting their resources. In general, NICE approves therapy when the incremental cost is £30,000/QALY; in the U.S., that figure is generally $50,000/QALY.

Medicare Negotiations

Deciding how to pay for the new generations of medical therapy is not limited to just this instance. Other gene therapies for the other form of hemophilia and sickle cell disease are coming to market. And while the use of gene therapies may be restricted to small populations, the same is not true for biologics – human-made proteins that impact our immune system. Those medications play a role in caring for patients with cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease. They can range in cost from $10,000 to $30,000 annually.

Medicare covers biologics as part of Part B (physician-administered infusions) or Part D (patient-administered injections). Four of the top 10 Part D drugs are biologics (the others include four medications for diabetes and 2 for anticoagulation); all of the top 10 Part B drugs, representing nearly two-thirds of the spending, are biologics.

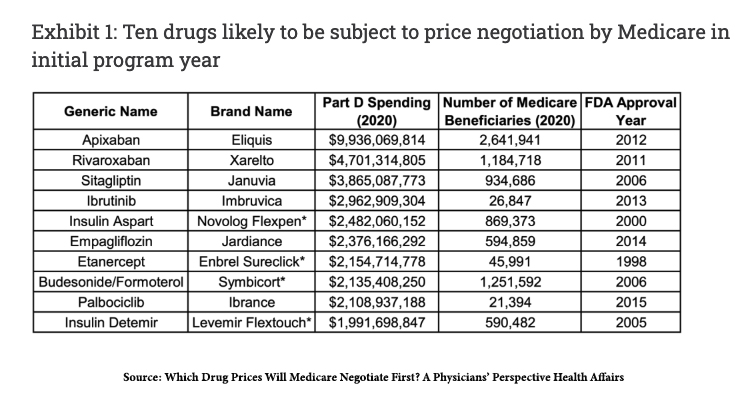

The upcoming Medicare negotiations already have fiscal handcuffs. The only drugs to be negotiated are Part D, patient-administered medications. They must be single-source drugs without generic or biosimilar drugs availability, in the case of biologics. Small molecule drugs must have been approved more than seven years ago; for biologics, that period is 11 years. Here is a chart of those medications likely to be negotiated according to Health Affairs. These drugs reflect 17.5%of Part D spending, $34.7 billion.

How exactly is Medicare expected to negotiate those prices?

“The legislation directs the secretary of HHS to consider evidence on the comparative effectiveness of treatments when proposing negotiated prices.”

QALYs are flawed, but they probably represent the measure we have used more than any other. To eliminate its use in these negotiations is to make the process wholly subjective, making it susceptible to influence and following the money answers who has the most to gain from influencing those decisions. The biggest lobby group spent over $323 million in 2022. These expenses can be found here.