Searching for Who

There is no consensus over the diagnostic criteria for Long COVID; with over 200 symptoms and no clear biomarkers, how can you identify those with Long COVID? The NIH’s Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) Initiative is designed to answer that question, among others, and this week released its first data on the constellation of symptoms that might define Long COVID.

At this point in recruitment, RECOVER involves 9764 participants, stratified as having or not having COVID and enrolling within or after 30 days of a COVID diagnosis. A diagnosis of COVID was based on a positive PCR test, a rapid test that could be performed at home, or antibody evidence of exposure to COVID. Symptoms were elicited from these individuals six months after the acute onset of their illness.

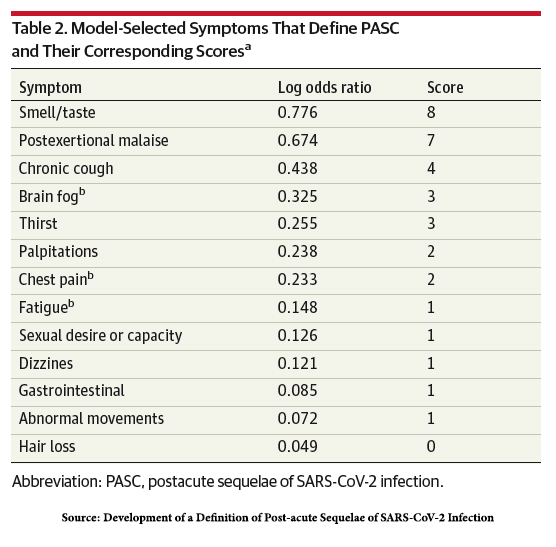

The study identified which of the 44 proffered symptoms might define post-acute sequelae of

SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) Long COVID’s new name. Moderate or severe symptoms reported by more than 2.5% of participants were considered; statistical manipulation, i.e., regression analysis, identified the most likely  symptoms. Several symptoms showed a greater than 15% difference in prevalence between the infected and uninfected:

symptoms. Several symptoms showed a greater than 15% difference in prevalence between the infected and uninfected:

- Post-exertional malaise (PEM) – 28% vs. 7% in the uninfected

- Fatigue – 38% vs. 17% in the uninfected

- Dizziness – 23% vs. 7% in the uninfected

- Brain fog – 20% vs. 4% in the uninfected

- Gastrointestinal symptoms – 25% vs. 10% in the uninfected

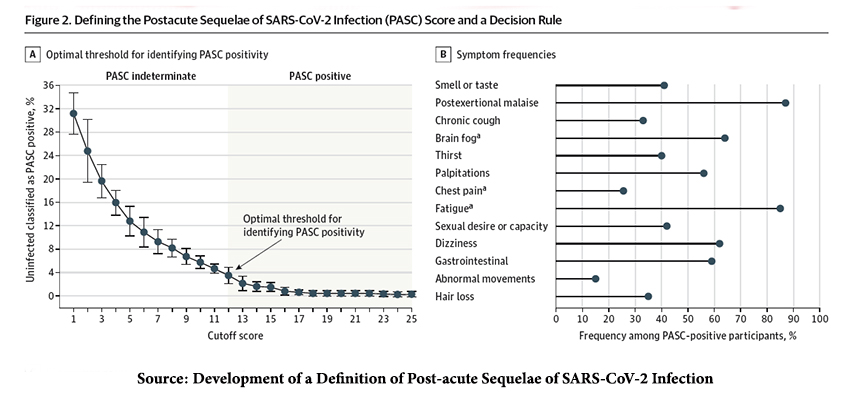

A scoring system weighing the symptoms to account for disparities in age, gender, race, and ethnicity was developed; a score of 12 or more was consistent with a “diagnosis” of PASC. The proportion of infected patients with a score “diagnostic” of PASC was 23%, but 3.7% of uninfected patients also “diagnostic” of PASC (false positives) – the scoring system is not perfect, but it is a start.

For a moment, let us accept the scoring and the cutoff.

- The incidence of PASC varied, being higher in those infected with the pre-Omicron “ancestor” strain than those infected by Omicron.

- 10% of those reporting an Omicron infection within 30 days of study enrollment had PASC. This rose to 17% in those enrolled 30 days after testing positive for Omicron. The incidence of PASC was 35% for those delaying enrollment in the pre-Omicron era.

- PASC was greater in the unvaccinated; 37% for those infected by the “ancestor” strain and 17% to 22% for those infected by Omicron. PASC was “diagnosed” in 20% of the reinfected.

- 39% of those hospitalized experienced PASC, 22% among those managed at home

- PASC was seen in 19% of males, 25% of females, 20% among those 18 to 45, and 28% among those 46 to 65.

There are several limitations to this study. The scoring algorithm must be “iteratively refined” as more data becomes available. There may be selection bias in those enrolling in the RECOVER study, and of course, all symptoms and their severity are self-reported. There are no known objective measures or markers that define a diagnosis of PASC. As the researchers conclude,

“Given the heterogeneity of PASC symptoms, determining whether PASC represents one unified condition or reflects a group of unique phenotypes is important. Recent evidence supports the presence of PASC phenotypes, although characterization of these phenotypes is inconsistent and largely dependent on available data. Accurate phenotypic stratification has important implications for investigations into the pathophysiological processes underlying PASC and clinical trial design. … This symptom-based PASC definition represents a first step for identifying PASC cases and serves as a launching point for further investigations.”

Two particular findings PEM, post-exertional malaise, and fatigue, have been reported by nearly all of those RECOVER characterized as having PASC. Might they be a phenotype?

Searching for Why

As with many academic centers, the University of California, San Francisco, opted to study the long-term effects of COVID. Their study, entitled Long-Term Impact of Infection with Novel Coronavirus (LIINC), looked at, among other things, cardiac function. Two tests of cardiac function, cardiac ultrasound and MRI looked at the anatomy, function, wall motion, and structural changes; there was little in the way of significant findings six months after the diagnosis of COVID by PCR testing.

To take another bite of the diagnostic apple, all patients, irrespective of their previous tests, were asked to return and undergo cardiac exercise testing, “the gold standard for measuring exercise capacity.”

Their study involved 60 participants median age of 53, 42% female, and 95% have had at least one COVID vaccine; most had the “ancestral” COVID strain, not Omicron. Two-thirds had symptoms that we would characterize as PEM at six months and persisted at 18 months.

“Those with symptoms completed less work despite higher perceived effort….”

The ability to complete an exercise protocol was diminished in 49% of those with symptoms vs. 16% in those without. In some instances, the ability to complete the exercise protocol was due to “deconditioning,” but 57% of those who we might characterize as having PEM had chronotropic incompetence (CI) – an inability of the heart to increase its rate of contractions (heartbeat) in response to the increasing demand of exercise. Those with CI generated 28% fewer beats per minute than those without the condition. Additionally, the researchers found elevated inflammatory markers and antibody levels early in PASC were associated with this reduced exercise capacity more than a year later. Epstein-Barr viral reactivation was seen in all of these PEM-inflicted individuals.

“Our findings suggest that chronotropic incompetence contributes to exercise limitations in LC [Long COVID]. … We did not find evidence of myocarditis, cardiac dysfunction, or clinically significant arrhythmias.”

Could some form of chronic inflammation or infection underlie PASC? And what to make of the finding of Epstein-Barr viral reactivation in all these individuals? Among the considered etiologies of CI is an abnormality of the humoral and autonomic nervous systems that control and coordinate our heartbeats—one last word from the researchers.

“Our study highlights the clinical challenge that many with symptoms have no objective findings on multimodality cardiopulmonary testing, emphasizing gaps between patient presentations and current evidence.”

We should note in passing that treatment to improve chronotropic incompetence, outside of the presumptive cases of PASC, involves exercise training that could improve heart function and quality of life or the use of pacemakers to increase heart rates.

Searching for Treatment

As reported by the Washington Post, the NIH RECOVER study seeks to use exercise training as one of five trial arms in treating PASC. Given the findings of fatigue and PEM in such a high number of these cases, as RECOVER has documented, and the measurable, objective physical finding, chronotropic incompetence, in the second study, you would think this is a very good idea.

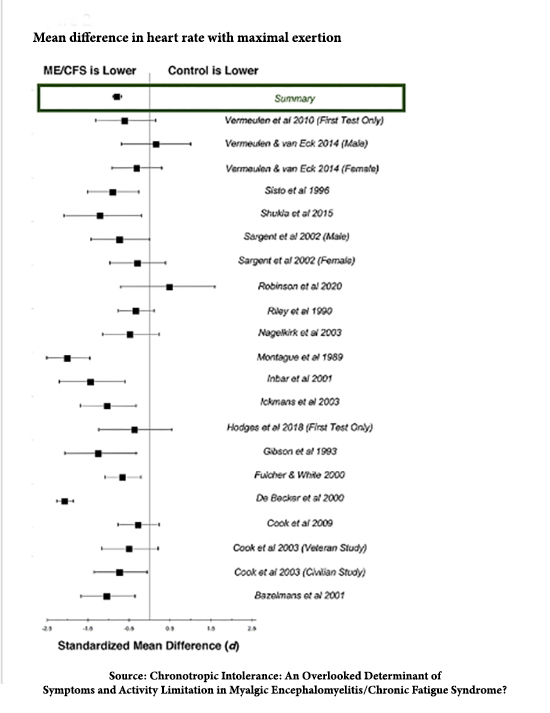

A meta-analysis of chronotropic incompetence and chronic fatigue (formally called Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) states:

A meta-analysis of chronotropic incompetence and chronic fatigue (formally called Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) states:

“This literature synthesis supports the presence of abnormally blunted HR responses to activity in people with ME/CFS, at both maximal exertion and submaximal VAT.”

The Forest plot to the right looks pretty convincing.

But patients, especially those with chronic fatigue, evidently feel otherwise. Two patient advocacy groups, Long COVID Justice and #MEAction, have called for the NIH trial to be stopped.

“Worst-case scenario, this would harm a lot of people.”

- #MEAction’s US advocacy director, Ben HsuBorger

In an echo of Tuskeegee, patients with chronic fatigue feel ignored and their condition trivialized. The value of exercise therapy, even at submaximal levels, is unclear, and patients are often told not to push their exertional limits. Many of these patients also have POTS, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, where standing results in dizziness and fainting. (Dizziness is the third most common symptom reported in the RECOVER study, even though it only scores 1 point in their PASC scoring system.)

How to manage these conditions is unclear.

“Researchers should prioritize studying potential cures or promising pharmaceutical interventions.”

- Charlie McCone, RECOVER participant and RECOVER patient advocate

“We don’t know what the role of exercise is.” That’s why, scientifically, it’s really important that we study it in a rigorous fashion, especially when there are competing viewpoints in the community, where some people think exercise is extremely harmful and other people think exercise is the key to recovery.”

– Dr. Matt Durstenfeld, one of the authors of the UCSF paper

Of course, without patient participation, it will be hard to do this arm of the study. And without these treatment trials, patients with PASC will be left with no clear therapeutic choices.

Source: Development of a Definition of Post-acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection JAMA DOI: 10.1001/jama.2023.8823

Reduced exercise capacity, chronotropic incompetence, and early systemic inflammation in cardiopulmonary phenotype Long COVID Journal of Infectious Diseases DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jiad131

An exercise trial for long covid is being criticized by some patients Washington Post