What It Is and Who It Helps

Established in 1965, Medicaid is designed to assist those who might otherwise struggle to afford healthcare. Unlike Medicare, which is primarily for seniors and certain disabled individuals, Medicaid serves a broader range of populations with different eligibility criteria set by each state within federal guidelines. Medicaid is the largest source of health coverage in the United States, covering over 80 million Americans in recent years.

Medicaid operates as a federal-state partnership, meaning that while the federal government sets broad guidelines, states have flexibility in structuring their programs. The program is jointly funded by the federal government and the states, with the federal share, the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) without a set limit and varying based on state income levels - from 50% to over 75% for the poorest states. States contribute the remaining funds. Most states took advantage when Medicaid was expanded under the Affordable Care Act because the federal government initially covered 100% and now 90% of those costs. [1]

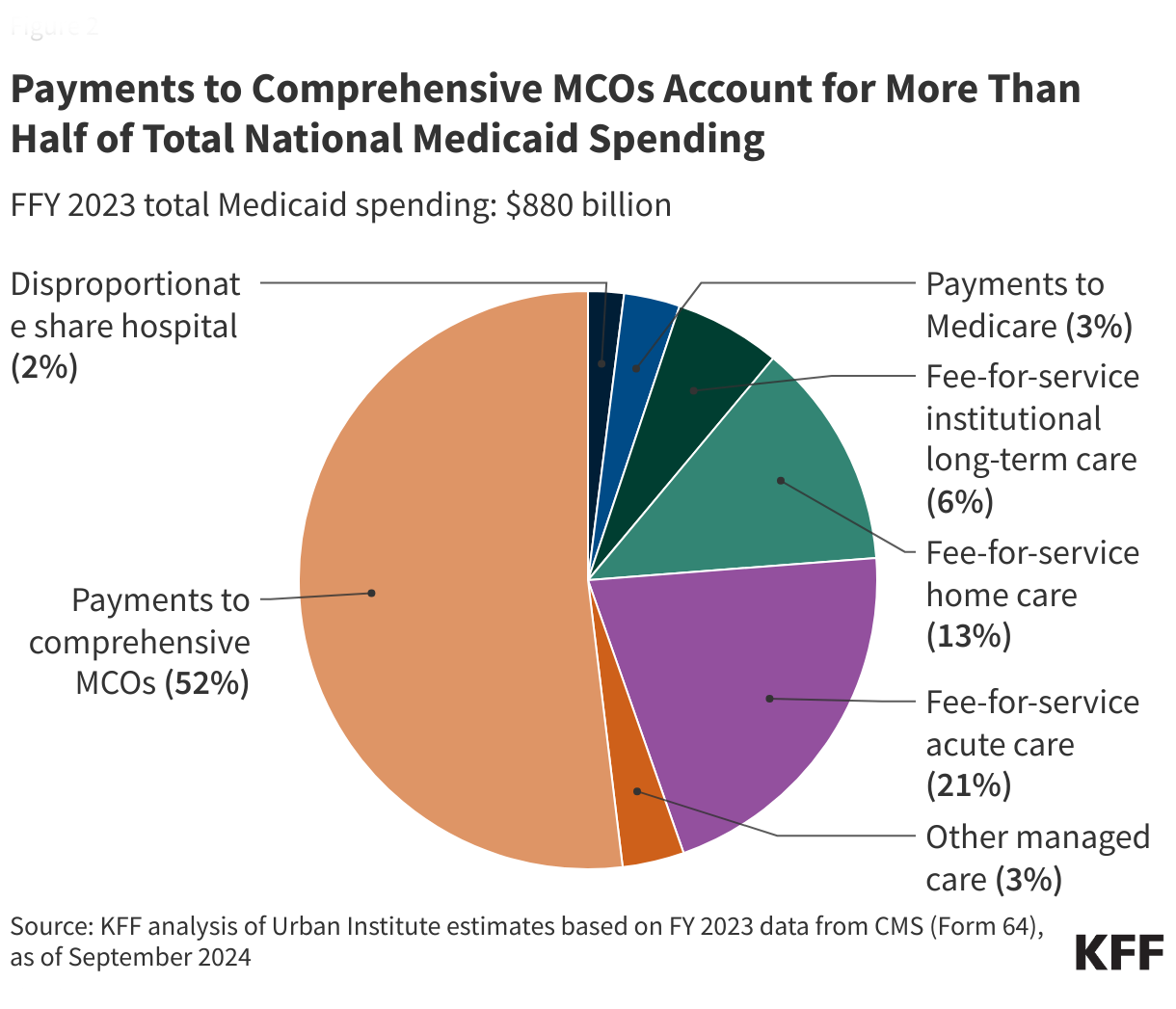

Medicaid provides essential services for vulnerable populations, including mandatory benefits, including hospital services, physician services, laboratory and X-ray services, and long-term care services. Each state administers its Medicaid program, leading to variations in eligibility requirements, benefits, and reimbursement rates. Medicaid also provides payments to hospitals serving many Medicaid and low-income uninsured patients to offset uncompensated care costs - “disproportionate share hospital” (DSH).

States can apply for waivers to test new approaches in Medicaid delivery; this is the source of the discussion around work requirements, although other waivers can impact optional benefits. Like Medicare Advantage plans, states can also provide optional benefits, such as dental care, vision care, prescription drugs, and home- and community-based services (HCBS) for individuals requiring long-term care.

Medicaid eligibility is determined based on income, household size, disability status, and other factors. Many states use the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) system to determine income eligibility. Medicaid enrollees generally pay little to no out-of-pocket costs for services. Children and pregnant women are exempt from most cost-sharing. However, states may impose nominal copayments, particularly for non-emergency services. Medicaid eligibility is often identical to the requirements for other assistance programs, such as SNAP and housing assistance. Again, those Medicare Advantage ads featuring dental and vision care and prescription plans are meant for the “dual-eligible” individuals receiving coordinated Medicare and Medicaid benefits.

Medicaid serves a diverse group of beneficiaries. Federal law mandates coverage for specific groups, including:

- Low-Income Families and Children – providing coverage to children in families with incomes too high for traditional Medicaid but too low for private insurance.

- Pregnant women with low incomes to ensure prenatal care and delivery services.

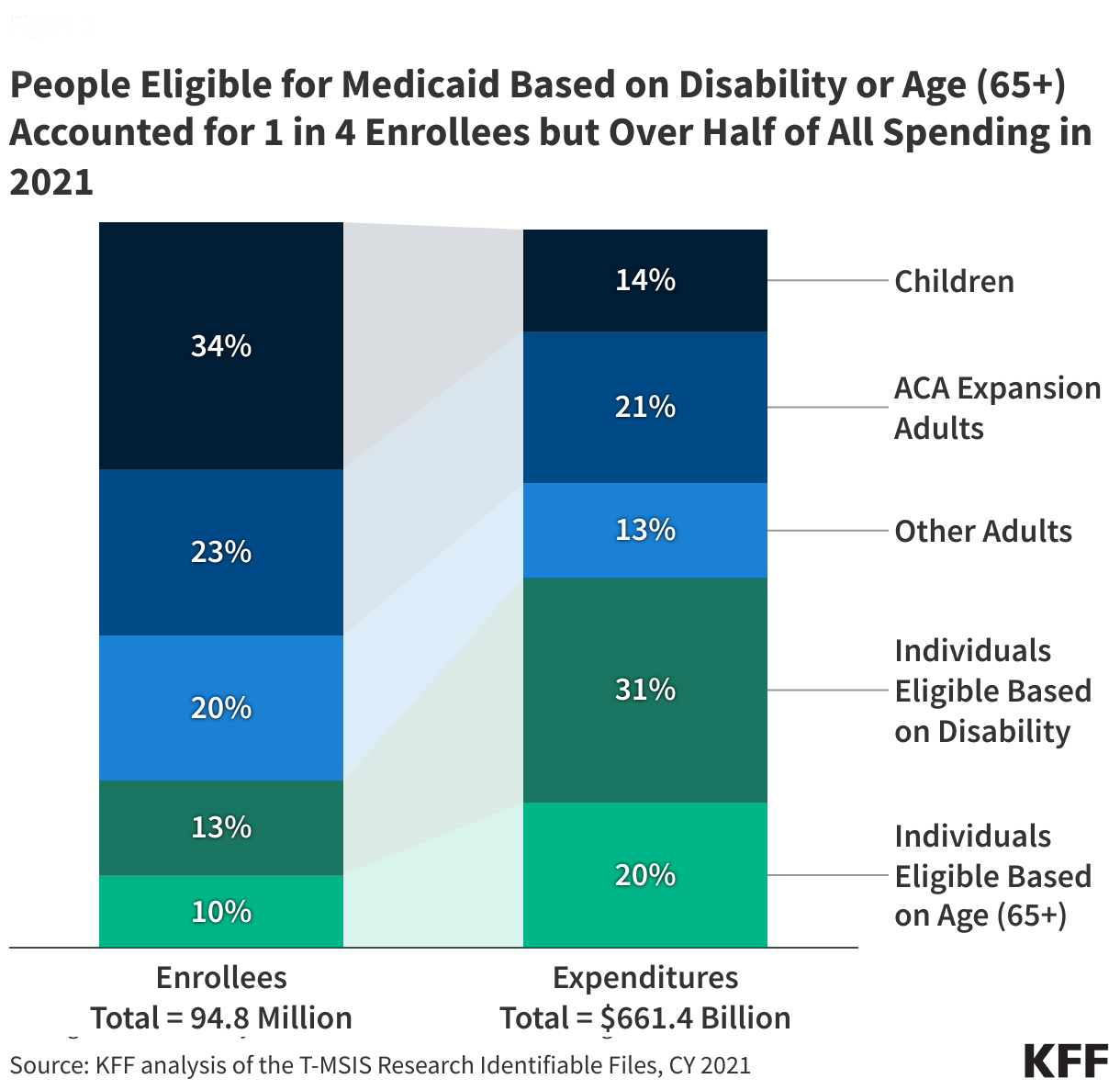

- Individuals with Disabilities – those receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or individuals with significant disabilities who require home or community-based long-term care services.

- Low-income adults earning up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Currently, for most states $21,597 for a single adult.

- Because beneficiaries eligible by age or disability have a higher rate of complex, chronic illness and utilize more long-term care, their costs are sixfold greater than for eligible children.

A Federal-State Balancing Act

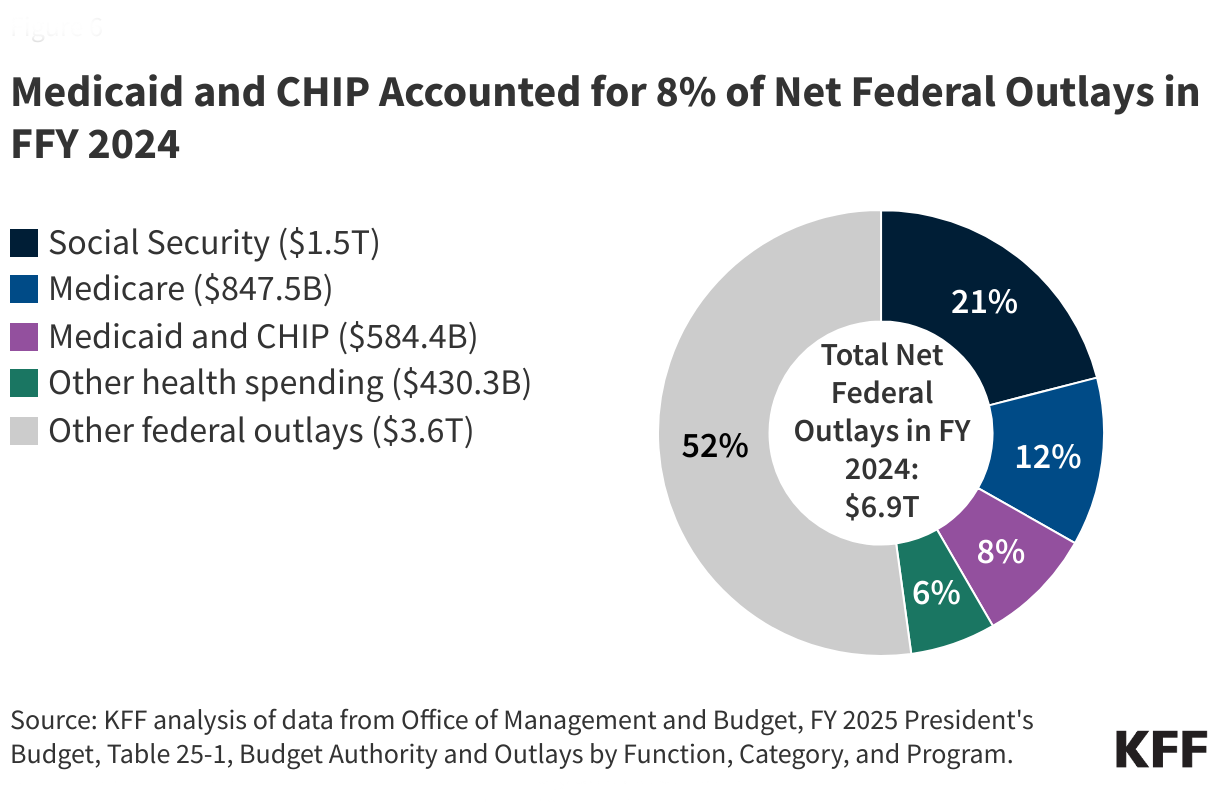

Because of the variation in state coverage and need, Medicaid covers a range of payments from as low as “$3,563 in Tennessee to $12,008 in the District of Columbia.” The currently battered about Medicaid spending of $880 billion represents federal payments of $606 billion or 69%, with states covering the remaining $274 billion. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid account for 41% of all spending. If the President is firmly committed to not touching Social Security or Medicare, any significant cost savings must come from Medicaid’s federal outlays. Of course, States may increase their  stakes, but that would mean taxpayers would be seeing little relief and, in some instances, tax increases. Many states already utilize Provider taxes, where health plans are taxed on a per-member basis to fund Medicaid. [3]

stakes, but that would mean taxpayers would be seeing little relief and, in some instances, tax increases. Many states already utilize Provider taxes, where health plans are taxed on a per-member basis to fund Medicaid. [3]

When Coverage Doesn’t Mean Access

Medicaid is a critical healthcare safety net. As with all human endeavors, it is imperfect. The “pain points” include uneven distribution of services as each state determines what is covered explicitly outside the federal mandates and eligibilities. The availability of care is often limited by access. Medicaid pays a far smaller percentage to healthcare providers; by that, I mean health systems and individuals. [2] This results in many physicians not accepting Medicaid patients, reducing the pool of services actually available, increasing wait times, and rationing by “hassle.” DSH provides “supplemental” payments that states make to supplement Medicaid “base” payment rates that often do not fully cover provider costs. Finally, Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term care in the US – as the cost of long-term care drains an individual’s assets, they reach a point when their income makes them eligible for Medicaid’s long-term care coverage. [4]

According to the Guardian reporting on information provided to Congress by the Congressional Budget Office,

“it would be impossible to reduce spending by $880bn without cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (Chip). That’s because after excluding Medicare, Medicaid, and Chip, the committee oversees only $381bn in spending – much less than the $880bn target ...”

The Fraud Factor: Real Problem or Political Scapegoat?

Again, Medicaid being a human endeavor, some individuals seek to game the system and are responsible for fraud and abuse. “Program integrity” is the job of both the federal and state governments. These “improper payments” or payment errors, described by the Government Accountability Office, “are either made in an incorrect amount or should not have been made at all.” According to their report of the $849 billion spent on Medicaid, they identified $50.3 billion in improper payments, roughly 6% - I hasten to add that fraud and abuse is an indeterminate subset of those improper payments; in fact the majority of improper payments “(79%) were due to insufficient information (or missing administrative steps), not necessarily due to payments for ineligible enrollees, providers, or services (i.e., since they may have been payable if the missing information had been on the claim and/or the state had complied with requirements).”

What Voters Think

In January, KFF conducted five virtual focus groups with 34 Medicaid enrollees from Medicaid expansion states that voted for Trump in 2024. Two groups voted for Harris, and three for Trump. Participants aged 18-65 had used Medicaid in the past year and were demographically diverse.

- Many Trump and Harris voters identified the economy as their top voting issue in the 2024 election.

- Both Trump and Harris voters valued their Medicaid coverage and its access to healthcare services. They valued Medicaid's role in protecting them from financial hardship, alleviating stress, improving health outcomes, and supporting their ability to work. Participants believed that losing Medicaid would be "devastating" and would lead to serious consequences for their physical and mental health while also exacerbating pre-existing financial challenges. They wanted policymakers to focus on improving Medicaid instead of cutting it.

- Participants opposed cutting Medicaid funding to pay for tax cuts that they did not believe would benefit them, expecting significant changes to the Medicaid program if federal funding were reduced.

- Most participants agreed that the government has a role in making health care more affordable and accessible. However, some Trump voters believed the private sector could.

- Many participants who were working part-time or not working said they wanted to work or work more hours but were unable to because of disability or because they were caring for young children or sick parents. More Trump voters supported a work requirement, and those not working were often convinced they would qualify for an exemption. Participants who were working generally felt confident in their ability to meet them. However, they worried about the burden of monthly reporting requirements and the critical value of Medicaid access in supporting their ability to work.

- Few participants recall hearing about changes to healthcare programs, including Medicaid, during the campaign or the focus groups. Some Trump voters suggested the cuts were aimed at removing undocumented immigrants from the program [5]. Some Harris voters felt the proposals reflected a pattern by Republican lawmakers to reduce benefits for poor Americans

- Many participants believed fraud exists, but views differed on whether it is a significant issue and the primary cause. Several Trump voters thought the problem was due to people enrolled who were not eligible. However, other participants, including Trump and Harris voters, felt that providers and insurance companies were more likely the primary source of problems.

The future of Medicaid hangs in the balance, with proposed funding changes and policy shifts that could profoundly affect millions of Americans. As discussions unfold, we must stay informed and hold our representatives accountable. Whether the goal is to preserve, reform, or cut Medicaid, the voices of those who rely on the program—and the taxpayers who fund it—should not be ignored. Watch closely because today's decisions will shape our nation’s health for years. Let’s see how Congress interprets Make America Healthy Again.

[1] Ten states opted not to participate. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Wisconsin, Wyoming. Of those, all but Kansas and Wisconsin voted for President Trump.

[2] A mid-level office visit, requiring 30 minutes, is currently paid at 80% of Medicare for New York’s Medicaid program or roughly $70. That is before the overhead costs of the practice are deducted.

[3] In New York, per-member taxation for Medicaid programs ranges from $25 to $126 per member.

[4] It is nearly impossible to hide assets in this situation. While an individual may continue to own their home, Medicaid will “look back” over the past 5-years before eligibility to identify assets transferred to family members, which they will “claw back.”

[5] Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for federally funded Medicaid.

Sources: Medicaid Financing: The Basics KFF

Medicare and Medicaid: Additional Actions Needed to Enhance Program Integrity and Save Billions GAO