Emotional expression is pivotal in the social dissemination

Emotionally charged online content can propagate rapidly, forming large-scale information cascades. As I have written, much of the literature has noted that content that arouses expressive negative emotions spreads widely and quickly. While content is important, less attention has been paid to the affective, emotional “content.” A new study of WeChat, China’s largest social media platform, examines emotions and offers some new insights.

The research sampled 100,000 random accounts, focusing on a random 10% of their postings, resulting in nearly 7 million individuals sharing roughly 400,000 online postings with their “first degree friends (i.e., strong tie contacts) or their acquaintances (i.e., non–first degree friends, weak contacts).” The postings covered a range of topics and varied in length. [1]

Discrete Emotions

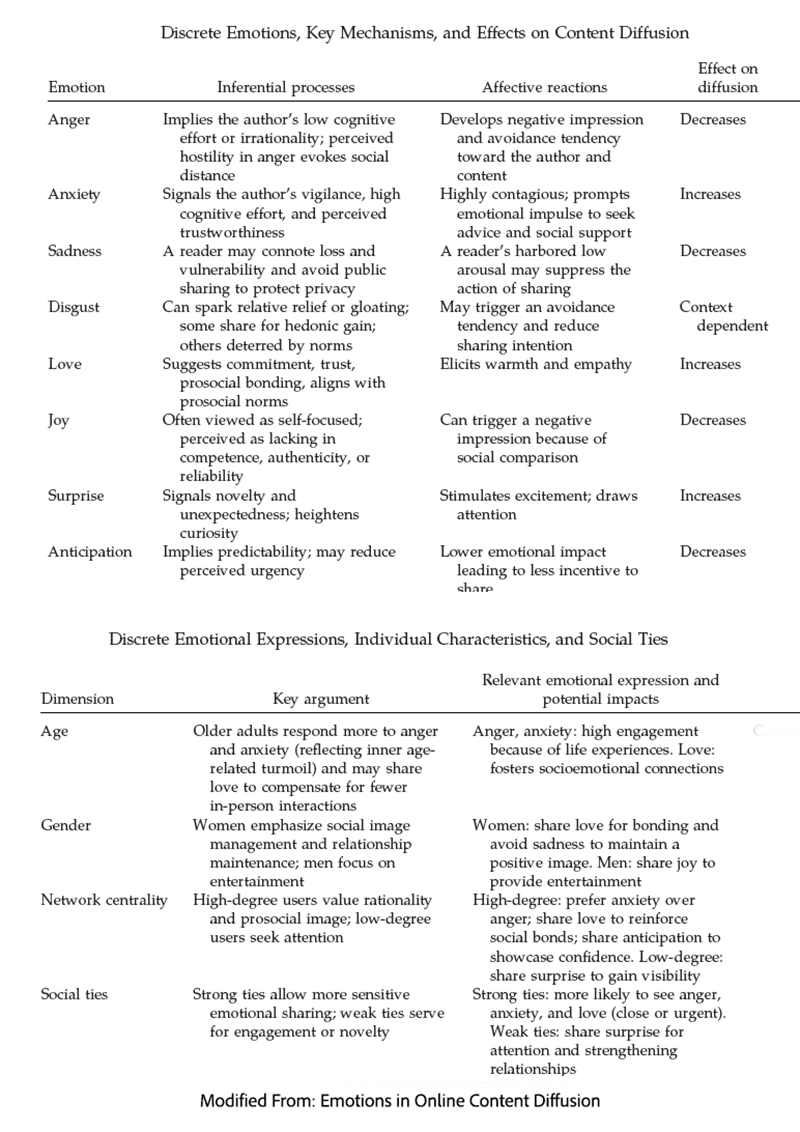

There are numerous ways to describe and therefore categorize emotions. Most prior research has focused on the valence, the positive or negative nature of an emotion, and the arousal, the activating or calming effect of an emotion. However, emotions with similar valences and arousals may result in different outcomes, e.g., anger and anxiety. Discrete emotion theory suggests that there is a limited core of basic, independent emotions that can be mixed to form the foundation for our more complex feelings. These discrete emotions are felt to be evolutionary in origin and therefore “manifest consistently in expression and recognition across individuals regardless of ethnic or cultural differences.” The authors suggest that awe is a combination of the two core emotions of anxiety and love. Research suggests that understanding discrete emotional connections is more predictive of behavior such as the helpfulness of online reviews, consumer purchasing decisions, and even reading online articles.

The researchers focused on the presence of specific words,” surprise, joy, anticipation, love, anxiety, sadness, anger, and disgust,” and their emotional meaning. They felt that “word-level emotional expression” was more objective and easily standardized, with actionable implications.

Cascades

Informational cascades describe how information spreads, influencing perspectives and behaviors across networks, like WeChat, X, and Facebook. The researcher characterized four properties of cascades in describing their “shape and dynamics.”

- Size: The total number of unique individuals who share the article, indicating its general popularity.

- Depth: The sharing by unique users, how well the information spreads to different social communities. Greater depth is more effective sharing.

- Maximum Breadth: The number of users at each degree of separation from the original posting. A broad but not deep cascade suggests the content spreads widely within the same large social community.

- Structural Virality: the shortest distance between sharing, describes whether the network is fueled from a central source, as we experience in a broadcast, or is it driven more by decentralized, peer-to-peer viral spread.

Beholder’s Share

Despite the asynchronous nature of writing to and reading on the Internet, there is an interaction between writer and reader, often termed the “beholder’s share.” Each reader brings their unique background, in the study characterized by reader demographics, along with their knowledge and emotions to the read, resulting in diverse interpretations. In addition to the content itself, the emotional tone of the author, intermingled with the reader's emotional expectations and similarity to the author, can drive and shape these informational cascades.

Findings

Few articles exhibit high values in each component of information cascades. Cascade size and breadth correlated with one another, as did cascade depth with virality. Anger and sadness were the least expressed emotions, and love, anticipation, and anxiety were the most common.

Positive Spreaders – Content rich in anxiety, love, or surprise traveled farther, faster, and deeper through networks. These emotions fueled broad reach, deeper penetration into communities, and extensive peer-to-peer sharing, making them highly viral.

Negative Dampeners – In contrast, anger, sadness, and—surprisingly—joy produced shallower, smaller, and less viral cascades. Even joy, despite its positive tone, often stalled rather than propelled sharing.

Mixed Effects – Anticipation reduced both cascade depth and structural virality, hinting that it may discourage peer-to-peer spread. Disgust, on the other hand, proved unpredictable—sometimes boosting virality when placed early in an article.

The study also found that all eight discrete emotions shaped who shared content and how it spread. Anger, anxiety, and surprise drew in older, more life-experienced audiences, along with love, perhaps to offset limited face-to-face contact. Women tend to prioritize maintaining relationships and a positive image, sharing love and avoiding sadness, while men tend to skew towards experiencing both sadness and joy. Emotional tone also determined whether content traveled via close-knit “strong ties” or looser “weak ties.” Highly connected users choose anxiety over anger, share love to strengthen bonds, and use anticipation to project confidence; less-connected users share surprise to gain visibility. Strong social ties encourage the sharing of sensitive emotions, such as anger, anxiety, and love, whereas weak ties utilize surprise to spark attention and novelty.

We are complicated creatures

Unlike prior studies that examine how emotions can affect one's feelings (valence) or behavior (arousal), this research found that negative emotional words reduced the spread of articles, while positive emotional words increased sharing. Interestingly, those individuals with strong social ties were more likely to convey disgust, which seems counterintuitive for sharing. The researchers suggest that this might be attributed to a “gloating effect” on their part. Moreover, specific words that we believe to be emotionally similar, such as "anxiety" and "anger," or "love" and "joy," had opposite impacts on sharing. We remain, despite all our efforts, complicated creatures, difficult to understand.

The most significant limitation to generalizing the researcher’s work is that there is no consensus on our discrete emotional words. Other word choices, like fear or shame, may drive other informational cascades; we do not know. But they have shown that in understanding our social communication, the meaning of words is both greater than we have anticipated and that all of communication can be lost in translation, as the beholder’s share interacts with the writer’s intent and ability to express their meaning.

[1] WeChat is primarily text-based, but allows for the inclusion of images and videos. The average article length is approximately 500 words; however, the sample included text lengths compatible with tweets and those found in newspaper or magazine articles. Topics included “politics, economics, business, society, sports, and technology, among others.”

[2] “Word-level emotional expression is defined as the linguistic expression of discrete emotions, including emotional keywords or phrases, degree words, and negation words.”

Source: Emotions in Online Content Diffusion Information Systems Research DOI: 10.1287/isre.2022.0611