From Apprenticeship to Algorithms

For decades, surgery has been taught as a craft, its technical and cognitive components shared from master to apprentice, surgical attending to resident. It is this “bottleneck” in education that has contributed to a growing shortage of surgeons and surgical care. Today, surgical education is transitioning from a time-focused apprenticeship to a competency-based assessment of the technical skills that are critical determinants of patient outcomes.

However, surgeon teachers rely on qualitative assessments, which lack objectivity and standardization. AI tutoring seeks to address the shortcomings of quantification and the inefficiency of apprenticeship by providing objective feedback and error correction during training. Its long-term vision is an “intelligent” operating environment capable of assessing and minimizing errors in human surgical performance. A new study in JAMA Surgery reports on the state of the art.

Intelligent Continuous Expertise Monitoring System (ICEMS) – A Digital Coach

ICEMS is an AI application designed by the authors to augment neurosurgical training by providing continuous assessment and real-time feedback on psychomotor skills. The system’s underlying algorithm quantifies expertise on a continuous scale from -1.00 (novices/medical students) to 1.00 (experts/neurosurgeons), capturing essential aspects of operative performance at 0.2-second intervals.

To overcome the “black box” problem in understanding AI “thought,” the ICEMS was built on understandable and relevant features of neurosurgery, the bimanual manipulation of a suction device that separates and removes tissue, the aspirator, and a device that stops bleeding, the bipolar forceps.

The ICEMS extracts five essential aspects [1] from simulation data: safety, quality, efficiency, bimanual cognition, and movement. An "error" is defined explicitly as a difference of more than 1 standard deviation from the expert benchmark for more than 1 second.

Trial by Simulation: Testing AI Against Human Instructors

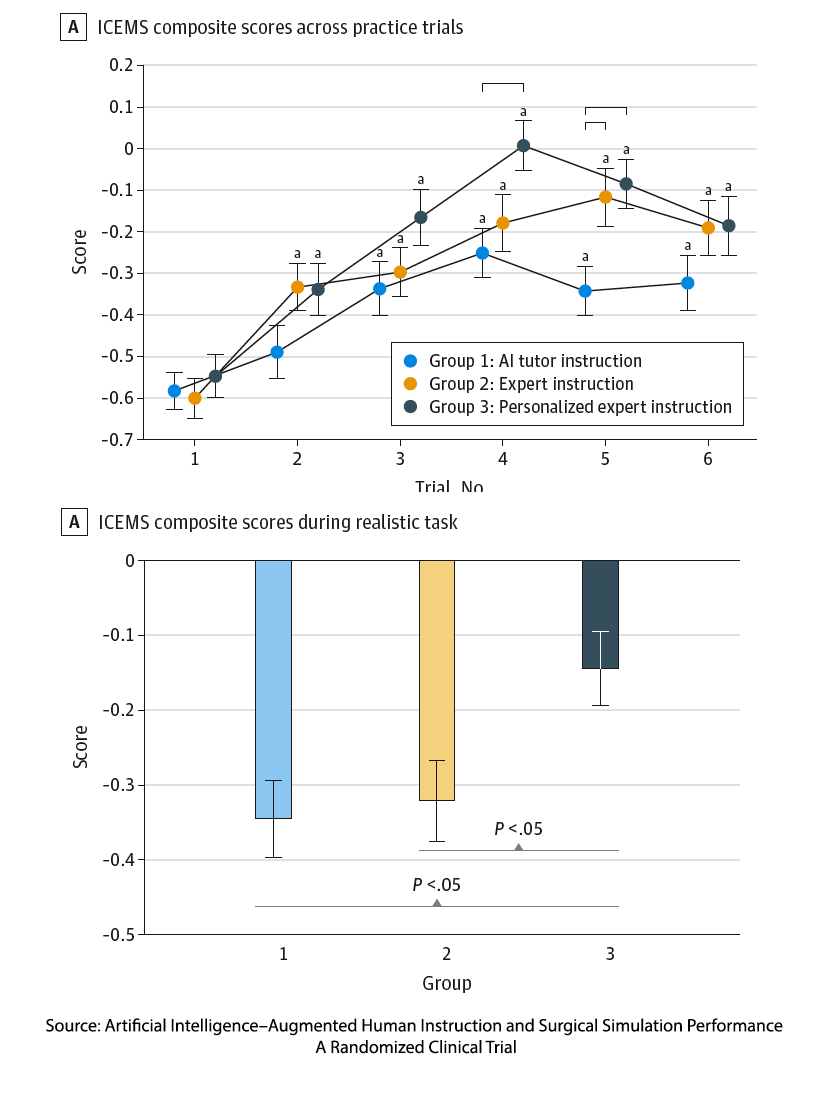

A randomized controlled trial enrolled 87 volunteer medical students from four Quebec medical schools to investigate the optimal approach for optimizing ICEMS in surgical training. Participants performed six 5-minute practice tasks, followed by a simulated, realistic “subpial resection” that minimized damage to the brain’s surface and underlying structures. Outcomes focused on improvement in surgical performance across repeated practice sessions and the transfer of skills in the resection scenario, along with secondary assessments of the participant’s emotional and cognitive “load.”

The students were randomized into three groups, and during the second through fifth practices, they received intraoperative instruction based on their randomly assigned groups:

- AI Tutor Instruction, where real-time verbal feedback was delivered from the ICEMS program when an error was detected.

- Expert Instruction, where the verbal feedback was provided by a neurosurgical resident who simply repeated verbatim the feedback from ICEMS.

- AI-Augmented Personalized Expert Instruction, where ICEMS alerted the instructor, again a neurosurgical resident, of the error; however, the instructor delivered tailored, personalized feedback without restriction to ICEMS wording, a form of human-AI augmentation.

The Study Found: Gains, Struggles, and Surprises

Patterns emerged that revealed the strengths and weaknesses of each instructional style.

Practice makes better, but not perfect. While all groups improved, given that the participants were medical students, unsurprisingly, none reached a level of surgical “expertise.” That said, there were improvements in both the risk of bleeding and tissue injury.

Practice makes better, but not perfect. While all groups improved, given that the participants were medical students, unsurprisingly, none reached a level of surgical “expertise.” That said, there were improvements in both the risk of bleeding and tissue injury.

Expert Instruction Delivered by a Human, in just repeating the advice of the algorithm, resulted in greater improvement than robotic, algorithmic words.

AI-Augmented Personalized Expert Instruction achieved the highest performance scores and significantly better transfer of skills in the complex, realistic scenario used to measure learning.

More Frustration. All groups experienced increases in negative emotions such as frustration and disappointment after practice. Importantly, the greatest emotional intensity and cognitive load came with personalized feedback, and appears to support, rather than hinder, learning in this setting.

A Conundrum for the Future of Surgical Training

The findings from this study make a compelling case that effective teaching requires more than data and instruction—it requires the human ability to translate knowledge into a form that matches the learner’s current skills and understanding. As the editorial accompanying the study points out, “real-time analytics cannot be delivered at scale by humans.”

While the AI system provided precise, real-time performance feedback, it was the human instructors who gave that data meaning, shaping numbers into lessons that students could absorb and learn from. When feedback was tailored to individual learners, performance improved not only in practice but also in complex, real-world scenarios. Even the simple act of hearing a human voice, rather than a synthetic one, improved engagement, underscoring the irreplaceable role of human presence in learning. As the authors write,

“…cultivating human expertise still demands a human-centered interface—one that preserves friction, nuance, and the motivation to improve.”

At the same time, the study reminds us that learning is not meant to be comfortable. Personalized expert instruction produced more frustration and mental effort than AI alone, yet it also achieved the highest performance. This tension reflects the principle of “desirable difficulty”: the right level of struggle fosters deeper learning and more lasting skills. Discomfort is not a flaw in the process—it is a feature.

Ultimately, AI can measure performance with extraordinary precision, but it cannot replace the human capacity to empathize, contextualize, and challenge learners at the right moment. Teaching, especially in high-stakes fields like surgery, depends on that uniquely human ability to bridge the gap between what the learner knows and what they must achieve.

[1] Safety: Healthy Tissue Removed, Bleeding characterized by total loss, rate of bleeding, pooling, and its rate of change. Quality: Tumor Volume Removed. Efficiency: Force Utilized by Aspirator and Bipolar For ceps, Blood Pooling, and its rate of change. Bimanual Cognitive: Bipolar Tip Separation Distance and change. Movement: Force, Velocity, and Acceleration of Aspirator and Bipolar Forceps.

Source: Artificial Intelligence–Augmented Human Instruction and Surgical Simulation Performance A Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Surgery DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2025.2564