“Eat until you are eight-tenths full, drink until you are ten-tenths full.”

- Confucius

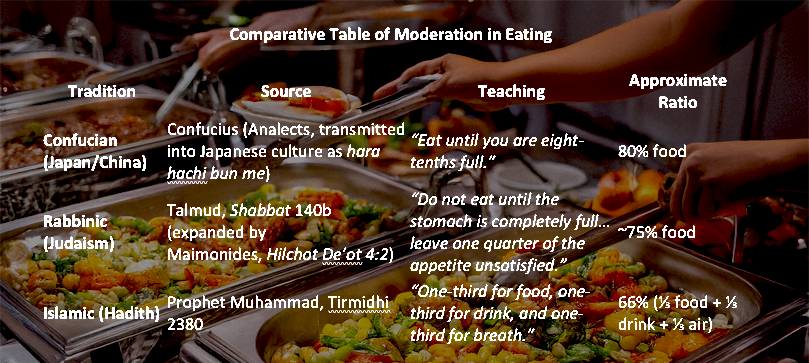

There is a Japanese phrase, hara hachi bu, 腹八分目, that means that you should eat until you are 80% full. It is a piece of advice that we might apply to both our diet of food and information. This philosophy of moderation, particularly with respect to eating seems to have originated in a Sanskrit word combination, Mitahara , from Mita (मित, moderate) and Ahara (आहार, taking food) adopted in Japan roughly 400 years ago.

Today, the underlying pharmacologic effects of the GLP-1s lend scientific credence to hara hachi bu. GLP-1 receptor agonists work by signaling the pancreas to release insulin, slow the emptying of food from the stomach, and, perhaps most importantly, communicates with the brain to enhance feelings of fullness. People taking these medications will sense of satiety that arrives sooner and lasts longer, along with a quieting of “food noise.” The GLP-1s strengthen the body’s “braking system” against overeating. Stopping short of satiety, at 80%, is a form of calorie restriction and is part of the weight loss accomplished by these drugs.

While GLP-1 therapies and hara hachi bu aim at aligning consumption with our body’s needs, hara hachi bu relies on conscious choice and cultural guidance, GLP-1 drugs reshape physiology.

There is increasing evidence that these drugs reduce cardiovascular risk and outcomes, although we have not been able to fully separate the effect based on weight loss from effects related to the drug alone. It is not a leap of faith to believe that hara hachi bu might have a similar impact on our health underscoring health emerges at the crossroads of biology and behavior, tradition and technology.

Physical Health, Spiritual Discipline

Culturally hara hachi bu is part of the Eastern tradition in medicine of moderation, in resisting excess; mindfulness, in being aware of our body’s signals of satiety; and balance, nourishment without overindulgence. As famed nutritionist Mary Poppins states, “Enough is as good as a feast.”

The almost viral popularity of GLP-1 drugs illustrate how the US easily accepts a biologic solution, literally allowing us to have our cake and eat it too. Hara Hachi bu works through cultural means that are far more difficult to overcome than issues of “access” or injections. However, both are reminders that moderation is just as relevant beyond the dinner table. In the modern world, our most overstuffed meal isn’t food at all—it’s information, served up as a constant buffet, consumed until we are bloated with facts, opinions, and distractions.

The Internet – The “Golden Corral” of Information

The information economy is designed like an all-you-can-eat buffet, urging us to keep piling our plates. Every scroll, click, and notification is another serving, and much like overeating, the result is a kind of bloat—not in the stomach, but in the mind. We grow anxious, distracted, and strangely unsatisfied, despite having consumed so much.

To combat this mental overconsumption, consider embarking on a seven-day "scroll-hara hachi bu" challenge. Set a daily limit for your digital intake, such as reducing screen time or limiting social media check-ins. You might also choose to curate a list of essential apps and silence notifications. Reflect on how these adjustments affect your ability to focus and your overall sense of well-being. This minimalist experiment could serve as a practical first step toward achieving digital balance.

The parallel with nutrition is striking. Just as eating beyond satiety leaves the body sluggish, consuming information without restraint dulls attention and erodes well-being. The problem isn’t that information itself is harmful—like food, it is vital—but that its constant, frictionless availability tempts us past the point of benefit.

Much of this is little more than mental snacking—filling time with calories of thought that fail to nourish. Far more of us consume ultra-processed information than the 50% of us consuming ultra-processed foods. As with nutrition, quality matters; a single serving of deeply engaged reading, offers more sustenance than ten half-skimmed gists abandoned in mid-scroll.

The lesson is familiar: fullness is not the same as nourishment.

Hara Hachi Bu for the Mind

We can learn to stop consuming information before we are mentally stuffed. It is a discipline of enoughness.

Unlike food, however, the buffet of information never closes. There is no biological signal that forces us to stop. The body eventually rebels against overeating, but the mind has no comparable mechanism; it will keep swallowing news, updates, and feeds long after value has disappeared.

Cognitive satiety is real: the brain has a limit, and beyond a certain point, new information doesn’t add clarity—it only muddies the waters. Practicing hara hachi bu for the mind means recognizing when you’ve reached that threshold and asking a simple question: Am I informed enough to act, reflect, or move on? If the answer is yes, that’s your 80 percent. Put the phone down, and let the mind digest.

Just as importantly, leave room for tomorrow. Mental hunger, like physical hunger, always returns—and that is not a failure but a feature. By stepping away before overindulgence, you create space for curiosity, attention, and fresh insight the next day.

The Art of Enough

The challenge of our modern life is not scarcity but abundance. GLP-1 medications show us how biology can be tuned to reinforce the natural brakes on overeating, while hara hachi bu reminds us that culture can shape restraint through mindful practice. Both point to the same truth: health emerges not from endless consumption, but from knowing when to stop.

Our information diet is no different. The constant buffet leaves us bloated with distraction rather than nourished by insight. Practicing hara hachi bu, discernment, allows us to reclaim our focus and attention. The art of enough is not about deprivation, but about creating space for balance, clarity, and growth.

So here is the question worth carrying forward: What would your days look like if you stopped not at exhaustion, but at enough?