A new Barron's article reports on multiple cases of alcohol poisoning in Brazil, mostly in and around São Paolo. According to the Brazilian Health Ministry, more than 100 cases of poisoning have been investigated, including one confirmed death, and 11 others are being investigated. Some bar patrons are in a panic. The culprit? Methanol – exactly what you'd expect.

"From chic Sao Paulo bars to Rio de Janeiro's beaches, Brazilians are on edge after a wave of suspected poisonings from tainted liquor has left people dead, blind, or in a coma." [1]

Methanol closely resembles ethanol in its chemical and physical properties, which makes it notoriously difficult to detect. That similarity also explains why it is the most common adulterant in liquor. It has been intentionally used to poison liquor and can also be present due to improper distillation techniques, usually from moonshine stills (See "Throw Away the First Cut: Popcorn Sutton & the Chemistry of Moonshine").

How can drinkers protect themselves?

There are a number of methods that can be used to distinguish methanol from ethanol. Most are not suitable for a bar.

- Odor - Absolutely not. While the two have a slightly different odor – methanol has a slightly sweet odor [2] – there is no way that the odor of methanol-tainted ethanol would be distinguishable from that of ethanol alone.

- Taste - Not a chance. Although the Chef's Resource website describes some subtle differences between the two, this is not an experiment you want to run. And, as is the case with odor, the only evidence that distinguishes drinking alcohol and a mixture of the two would be the presence of a corpse in the latter case.

- Solubility - Again, not a chance. Both ethanol and methanol are infinitely soluble in each other and in water. The same holds true for a mixture of the two.

-

The iodoform test [3] is a bit of chemistry nostalgia, harkening back to the days before sophisticated analytical instrumentation was available. It is an instant colorimetric analysis that is quite reliable in detecting molecules with certain chemical features.

Unfortunately, it works "backwards" in this case. Here's why (Figure 1).

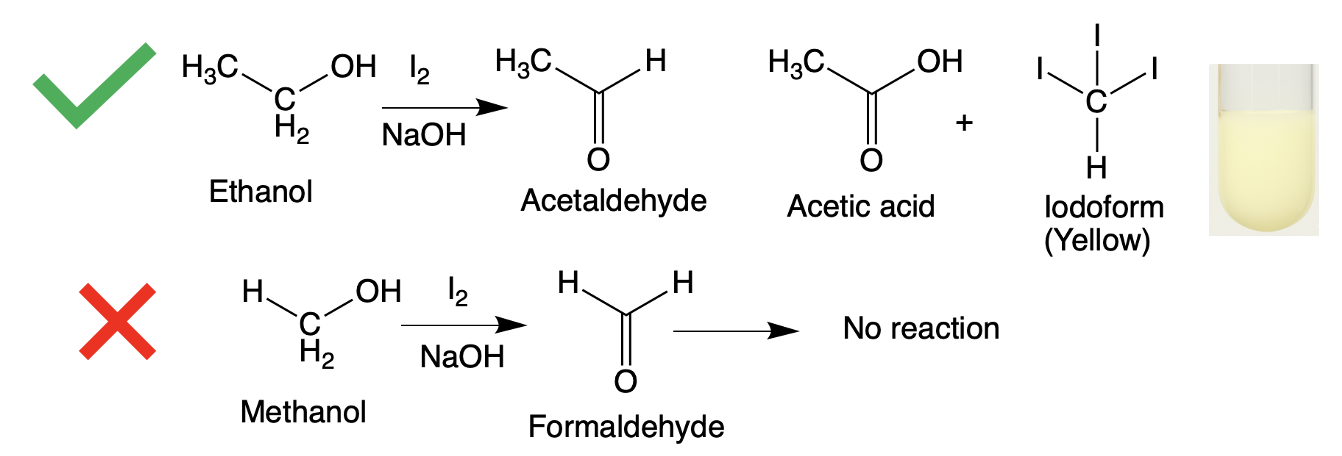

Figure 1. (Top) Ethanol is oxidized by iodine to form acetaldehyde, which then reacts again to form acetic acid and iodoform, a yellow precipitate (shown in test tube). (Bottom) Methanol is also oxidized by iodine to form formaldehyde, which cannot form iodoform (CI3).

Another strike against methanol

Metabolism plays a big role in the toxicity of methanol. While ethanol is rapidly converted to acetaldehyde (which does plenty of damage in its own right) and then harmless acetic acid, methanol turns into formaldehyde, which is even more toxic. And metabolism makes things even worse.

Formaldehyde is then metabolized to formic acid, the chemical weapon used by a number of species of stinging ants. Nasty stuff. Perhaps worse, there is no quick pathway to clear formic acid; it can accumulate in the eyes and cause a number of problems, including blindness. This is why drinking methanol can cause blindness.

So, while the iodoform test might be useful in detecting ethanol in a glass of methanol – something that will never be on a cocktail menu – it does not work the other way around.

What does work?

Chances are you’re not carrying around an infrared detector (~10 pounds), a compact mass spectrometer (~25 pounds), or an NMR spectrometer (~20 tons — you know this as an MRI) to your favorite bar in São Paulo. These are the gold-standard laboratory tools that can separate and identify methanol and ethanol with absolute confidence, but they’re obviously impractical for anyone outside of a lab.

Unfortunately, although there are a number of enzymatic assay kits under development, consumer-level methanol test kits for bar use are not yet broadly available [4]. Public health experts have noted that while prototype dip-strips and smartphone-linked devices are in development, no validated consumer strip has hit the market.

Perhaps the closest to "success" is a handheld electronic detector, called the Alivion Spark M-20, which can give a methanol readout in minutes. Downside? It costs thousands of dollars and looks like this.

The Alivion Spark M-20. Not ideal for downing Jello shots. Image: Alivion website

Bottom line

I'm afraid that you're still pretty much on your own if you choose to drink in São Paulo. Until a simple dip-strip hits the shelves, your best defense remains factory-sealed bottles, trusted venues, and maybe a Diet Coke.

NOTE:

[1] Facundo Fernandez Barrio and Fran Blandy, Barron's Magazine. 10/3/2025

[2] NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

[3] Vogel’s Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry, 5th ed. (Iodoform reaction).

[4] The Guardian, “How can I tell if there’s methanol in my drink?”, Nov. 23, 2024