"With the wrong metaphor we are deluded; with no metaphor we are blind."

- Jonathan Haidt, The Happiness Hypothesis

This essay is a thought experiment—a physician’s attempt to trace, through metaphor and evidence, why certain chronic diseases are rising today and what that says about our relationship with the microbes that share our bodies. We first need to understand what kind of beings we truly are.

We are holobionts

While our bodies are composed of millions of cells, all of which are recognized as self, we also contain others. From the mitochondria that power our cells to the bacteria in our gut, we live in constant collaboration, co-developing, exchanging metabolites, and co-evolving so tightly that we are considered a single ecological and evolutionary unit – the holobiont. Our shared genetic repertoire, the hologenome, shapes our health, disease, and adaptation. To that end, as Raghuveer Parthasarathy writes in So Simple a Beginning, the

"[The] gut microbiome is, in a sense, an organ, serving a physiological role in its host despite not being composed of the host’s own cells."

If the gut microbiome functions as an organ, disruptions to its ecology may help explain the rise of modern illnesses. The wealth of studies associating a “Western diet” with an increase in specific non-communicable diseases has a recognized biologic underpinning. As does the MAHA stress on what we eat, minus the baggage of Big Whoever’s intent.

The rise of widespread sanitation, Norman Borlaug’s Green Revolution, modern medical care, including antibiotics, vaccines, and biologics, has arguably saved millions of lives and reshaped our environment. These changes, occurring in a blink of evolutionary time, may have unintended consequences for holobionts, such as ourselves, whose niche was formed over longer timescales.

As science writer Moises Velasquez-Manoff warns, perhaps with some hyperbole, we may be experiencing “an extinction crisis within” our own bodies. Antibiotics, while lifesaving, can act like napalm, flattening microbial ecosystems. Urban living and hyper-clean habits reduce contact with soil, plant, and animal microbes that once refreshed our internal diversity. The result is a loss of microbial “novelty”—a narrowing of the ecosystem that keeps inflammation and disease in check.

To understand how we arrived at this point, it helps to trace one of the strongest cultural forces behind this internal disruption: our war on germs.

Driving Forces

One of the most significant of the driving forces is our complicated relationship with “germs.” The term, from the Latin germinis, once meant a “seed” or “offshoot,” but centuries of medical discoveries transformed it into a symbol of disease. Our faith in the germ theory of illness brought immense progress—but also a tendency to view all microbes as enemies. As Ed Yong reminds us, “First we learned to fear germs, then we learned to love our microbiome. The problem is that the latter view is just as wrong as the former. … There’s really no such thing as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ microbe… their relationships are contextual and ever-shifting.”

Long before Yong expressed our more nuanced understanding, armed with this fear, we sterilized our surroundings and ourselves with a variety of antibiotics, antiseptics, disinfectants, filters, and UV light.. The “hygiene hypothesis” suggests that limited exposure to everyday microbes leaves our immune systems undertrained, more likely to overreact later in life with allergies or autoimmune disorders. Microbiologist René Dubos, whose study of soil bacteria paved the way for the antibiotic era, foresaw this dilemma, arguing that changing ecological circumstances can weaken the host and trigger disease in what were once resistant individuals.

Our diets, too, have reshaped this internal landscape, influencing which microbes thrive—and which vanish. What we eat becomes the harvest our microbes feed upon. To them, we are Demeter, the giver of sustenance. In experiments cited by Velasquez-Manoff, mice on fiber-rich diets supported thriving gut ecosystems. In contrast, those on “Western-like” diets lost diversity and developed inflammation as microbes turned to digesting the gut’s protective mucus, separating us from our microbes. Over time, key species disappeared entirely, “starving the microbial self,” as mice mothers on such diets pass ever-smaller microbial legacies to their pups. Extinction is proceeding faster than regeneration, passed down through generations. These dietary patterns are products of our personal choices and an industrial food system shaped by economics as much as biology.

The Role of Industrial Food Systems

In some sense, these are the climate engineers of our microbiome. The risks of non-communicable disease pandemic, “flare up, triggered by stresses and a composite of many factors that are quite different to those assumed by the contagion model.” Sound epidemiology must therefore integrate host vulnerabilities. In high-income countries, mortality tracks with the prevalence of diet-driven ills, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, all linked to social and nutritional inequality. Our food production has reduced nutrient starvation, a remarkable achievement, but intensive production systems “tend to be troubled by the production of surplus and the resulting variations in farm-gate prices.” The economic choice is to “vent” the surplus through the proliferation of standardized products, which reduces industrial waste, but results in “at-scale production methods” (think the NOVA classification) that can have downstream dietary and public health impacts. Our food chains may have created new forms of malnutrition, in the form of obesity and foods lacking in micronutrients. Ground zero for those effects lies within our microbiome.

Rewilding

Rewilding refers to the process of restoring missing species and ecological processes, enabling an ecosystem to sustain itself once again. Within us, it begins with restoring lost microbes and the conditions they need to thrive.

In the experiments in mice described earlier by Manoff, the restoration of fiber to the diet resulted, over time, in the restoration of the gut microbiome and its habitat. But that restoration may require reintroduction of germs, for example, Helicobacter pylori, which is better known for its causative role in peptic ulcer disease. Many studies have found that individuals carrying the stomach bacterium H. pylori are less likely to develop allergies, such as asthma. The germ appears to train the immune system toward tolerance, altering gut microbes, and nudging and rebalancing regulatory T-cells away from the overreaction that drives asthma.

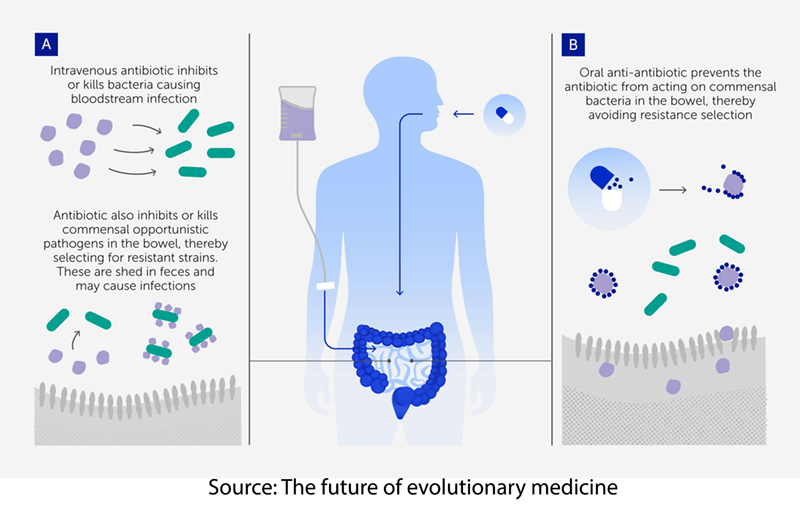

We can also alter evolutionary driving forces within, beginning with continuing to make inroads in reducing the use of unnecessary antibiotics, both in our food supply and our healthcare system. Antibiotic stewardship by physicians and our animal farmers is a growing necessity. The Cochrane review found some efficacy in the use of probiotic “beneficial” bacteria and yeast in reducing diarrhea associated with antibiotic use. Fecal transplants are effective in C. difficile infections that account for 30,000 annual deaths and carry a 6 to 11% mortality (For comparison, the mortality from open heart surgery is roughly 2%). We can even consider anti-antibiotics, which are binding agents that capture or chemically inactivate residual antibiotic molecules in the gut, thereby blocking the evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacteria while leaving the drug’s infection-fighting action elsewhere intact.

We can also alter evolutionary driving forces within, beginning with continuing to make inroads in reducing the use of unnecessary antibiotics, both in our food supply and our healthcare system. Antibiotic stewardship by physicians and our animal farmers is a growing necessity. The Cochrane review found some efficacy in the use of probiotic “beneficial” bacteria and yeast in reducing diarrhea associated with antibiotic use. Fecal transplants are effective in C. difficile infections that account for 30,000 annual deaths and carry a 6 to 11% mortality (For comparison, the mortality from open heart surgery is roughly 2%). We can even consider anti-antibiotics, which are binding agents that capture or chemically inactivate residual antibiotic molecules in the gut, thereby blocking the evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacteria while leaving the drug’s infection-fighting action elsewhere intact.

Restoring what was lost is only part of the challenge; resilience demands living systems that can adapt and recover from adversity.

Resilience

Our holobiont nature cuts both ways; there is no free lunch. The microbes that sustain us also depend on us for food, shelter, and transmission—and their interests sometimes diverge from ours. As Neil Theise observes, resilience in complex systems lies in “not too much randomness, not too little,” allowing adaptation and recovery after disruption.

True resilience extends beyond biology. As Lars Hartenstein of the McKinsey Health Institute notes, our daily choices shape health far more than clinic visits can. Building health literacy empowers individuals to steward their own metabolic ecosystems—choosing foods, medicines, and lifestyles that sustain balance rather than erode it. Sy Syms was correct, well-informed individuals make more intelligent trade-offs, demand better products and policies, and ultimately drive the systemic changes that healthier societies require.

Modern life has provided us with tools to extend longevity, yet it has also introduced vulnerabilities that are rooted in evolution itself.

Evolution Outpaced

Our shifting environment—especially in terms of diet, sanitation, and medicine—has brought enormous benefits, but it has also exposed new forms of vulnerability. As The Future of Evolutionary Medicine notes, lifestyle changes can modify disease risk, yet they also expose the limits of evolution’s slow pace. Our physiology, shaped over millennia, now faces pressures measured in decades.

“We contain multitudes.” – Walt Whitman

Blaming single villains—be they corporations, additives, or the microbe du jour—misses the deeper truth that our own choices, policies, and metaphors shape the microbial worlds within us. MAHA moms are, in a sense, the first responders; however, they are not the last word. The kabuki of Secretary Kennedy and his wellness advisors shows that they are not serious people, preening about, self-congratulating one another on ending the use of food coloring. If we are the “gods” of our inner ecosystems, stewardship is our responsibility. Government incentives and public education must align behind this biological rewilding, supporting fiber-rich, nutritional foods, curbing the use of antibiotics in medicine and agriculture, and redesigning food systems that currently reward calorie surplus over nutrient diversity. Progress can begin today as every meal and prescription pad becomes an act of ecological care. By tending to the health of our holobiont selves, we not only quell the inflammatory weather inside but also chart a model for healing the larger planet we share.