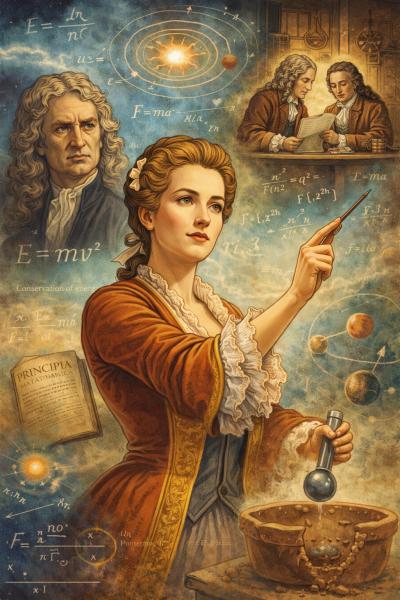

The year was 1706. The King of France was the Sun King, Louis XIV, and French Science was entering its heyday, at least for men. Forty years earlier, King Louis had established the royal French Academy of Sciences (Académie des sciences) to promote and protect French scientific research and formalize scientific inquiry. It was also the year that Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet, the publicist and translator of Newton’s works, was born.

Luckily for her, she came from an intellectual and aristocratic family, which provided her with an unusual education and early exposure to eminent intellects at her father’s salon. Ultimately, she became one of about twenty individuals of her day able to comprehend the advanced concepts of math and physics necessary to understand, translate, and correct Newton’s work.

If you have heard of the Marquise du Châtelet, most likely it was as Voltaire’s mistress, handmaiden, or muse. But she contributed so much more. After all, it was du Châtelet who translated, corrected, made accessible, and augmented Isaac Newton’s work, and proposed new theories of her own that get lost in titillation. Her affiliation with Voltaire spurred her scientific investigations; the two had friendly competitions, even building a laboratory on her estate to test competing theories. However, this obscured her status as a significant physicist and mathematician. To be sure, both Voltaire and encyclopedist Diderot held her work in such high esteem that they publicized her writings (some in direct format) in their respective encyclopedias, with Voltaire poetically acknowledging that du Châtelet's mathematical expertise was a crucial aid in understanding the technical parts of Newton's Principia. But like many an intelligent and accomplished woman of science of that day, and ours, she was derided.

“A woman ... who conducts disputations about mechanics, like the Marquise du Châtelet, might as well also wear a beard; for that might perhaps better express the mien of depth for which they strive." - Immanuel Kant

Voltaire and du Châtelet’s collaborations or contretemps, as the case may be, allowed her to be the first woman to have a scientific paper published in the French Academy when she took on Voltaire’s views of fire in 1738.

Most famous for her translations of Newton’s Principia into French, its second edition contained her extensive commentary, which comprised almost two-thirds of the second volume. The text, published posthumously in 1756, is the standard French translation to this day.

Newton's work in Principia was not perfect. Du Châtelet not only translated his work from Latin to French, but corrected and added to it, including her derivation of the notion of conservation of energy from principles of mechanics. Her commentary also contained her description of the System of the World and analytical solutions to disputed aspects of Newton's theory of universal gravitation.

- Du Châtelet’s corrections helped support Newton's theories about the universe, which suggested that gravitational attraction would cause the Earth's poles to flatten, bulging the Earth outwards at the equator.

- She proposed that different planets had different densities to correct Newton's belief that the Earth and other planets were made of homogeneous substances.

- She clarified and confirmed Newton's theory on the effects of the Sun and Moon on the tides.

To undertake this formidable project, du Châtelet continued studies in analytic or Cartesian geometry, mastered calculus, and read important works in experimental physics. Her rigorous preparation afforded her commentary a wealth of substantive, accurate information, drawn from her research and from the work of other scientists she studied or worked alongside.

This helped du Châtelet greatly, not only with her work on the Principia but also in her other important works, such as the Institutions de Physique, the first of two editions published in 1740, when she was 34. The Institutions covers a wide range of topics, generally the stuff of natural philosophers, which blended a religious and scientific view of the universe, including the principles of knowledge, the existence of God, hypotheses, space, time, matter and the forces of nature, and the nature of reasoning largely on Descartes’s principle of contradiction and Leibniz’s principle of sufficient reason. Several chapters addressed Newton's theory of universal gravity and associated phenomena. It circulated widely, translated into German and Italian, republished in Paris, London, and Amsterdam, generated influential and heated debates, contributing to her becoming a member of the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna in 1746.

Du Châtelet Critiques Major Thinkers of the Day

Echoing more modern beliefs, du Châtelet criticized John Locke's philosophy, emphasizing the necessity of the verification of knowledge through experience and rejecting the prevalent “thought experiments” of the day and the mathematical laws favored by other prevailing “greats”. She resolutely championed the existence of innate free will and favored universal principles that precondition influenced human knowledge and action

A “Force” of Nature

Du Châtelet's contribution to the concepts of force and momentum was the hypothesis of the conservation of total energy, distinct from that of momentum. In doing so, she became the first to quantify its relationship to mass and velocity based on her own empirical studies. Inspired by the theories of Leibniz, she repeated and publicized an experiment originally devised by Willem's Gravesande in which heavy balls were dropped from different heights into a sheet of soft clay. Each ball's kinetic energy, as indicated by the quantity of material displaced, was shown to be proportional to the square of the velocity. She showed that if two balls were identical except for their mass, they would make the same size indentation in the clay.

Not one to go out with a whimper, the Marquise took a lover ten years her junior, mothered a daughter, and died shortly thereafter at age 42. Who knows what she could have achieved had she lived as long as Newton, who died at 84.