The study doesn’t accuse anyone of fraud. Instead, it shows how bias can creep in through ordinary, defensible choices that help determine whether a finding ends up as a modest null result or a headline-worthy “effect.” That is why policy needs a research red team: an institutionalized group whose role is to challenge favored analyses, test alternative assumptions, and ask whether a conclusion survives sustained skepticism.

Bias Requires No Bad Actors

Nearly every viral headline from the social sciences has detractors concerned about bias, a cluster, rather than a solitary force, that can push results and impact in systematic directions. Well-known examples include the overpublication of statistically “significant” but practically trivial findings, the quiet disappearance of null results, p-hacking and cherry-picking, and large datasets that allow researchers to shop for outcomes. Looming behind these technical issues is another concern: conflicts of interest, which in academia are often ideological rather than financial.

To understand how ideology might shape results even when researchers act in good faith, a new study in Science Advances attempts to tease out the role of ideology in research using a “unique crowdsourced experiment” in which different research teams, given the same data, were asked to test and model a specific hypothesis. This is not an easy problem. There is no experimental setting to isolate a potential role for ideological bias, and those biases can enter the research framework at many points, from formulating the hypothesis to designing the research methodology. The original research, the dataset for this new study, noted that

“No two teams arrived at the same set of numerical results or took the same major decisions during data analysis.”

The current study seeks to determine whether this “dispersion” depends upon the researchers' views.

Same data, same question—very different answers

Same data, same question—very different answers

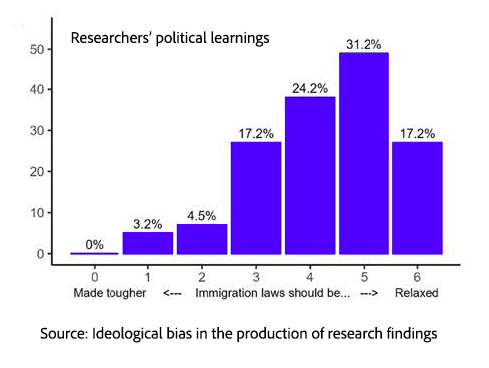

The original experiment gave 71 independent research teams the same dataset and the same question does “immigration reduce support for social policies among the public?” They also collected data on the researchers’ personal views of the issue. Specifically, whether immigration laws “should be made tougher” or “should be relaxed.” Given the concerns voiced in academia and the media, mainstream and extreme alike, it is unsurprising that the teams produced 1253 distinct statistical estimates, ranging from strongly negative to strongly positive. And yes, the teams’ political learnings on immigration align with the direction of their results.

Modeling Choices Shape the Results

Modeling Choices Shape the Results

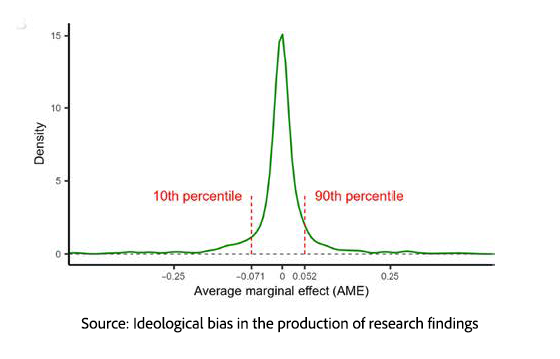

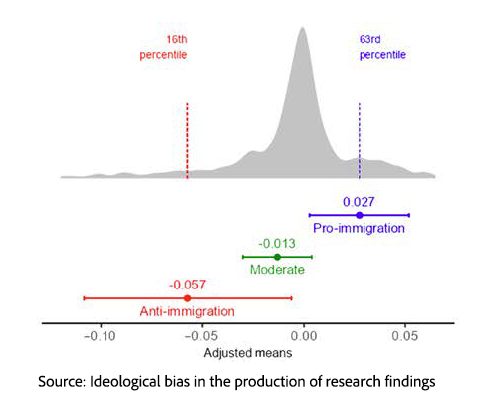

To compare the many models, the authors focused on a common metric: the average marginal effect (AME), which captures how changes in immigration levels are estimated to affect support for social programs. Most models clustered near zero, suggesting little to no effect. But the distribution had long tails on both ends, meaning some defensible models produced strong positive or strong negative effects. Put simply, depending on the analytic choices, a 1% increase in immigrant share could be estimated to reduce support for social programs by about 7%, or increase it by about 5%. The data themselves did not dictate a single answer; the modeling choices did.

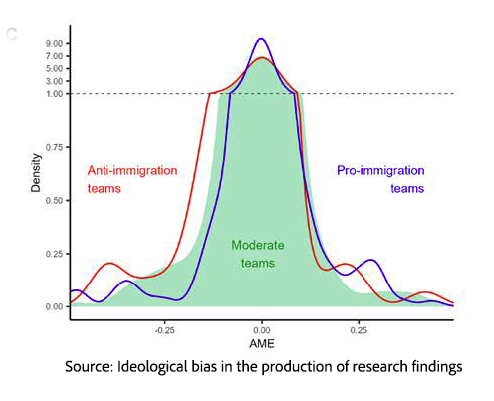

When we overlay political leanings on the middle portion of the findings, anti-immigration teams are more strongly represented in the negative estimates, and pro-immigration teams are more strongly represented in the positive estimates.

When we overlay political leanings on the middle portion of the findings, anti-immigration teams are more strongly represented in the negative estimates, and pro-immigration teams are more strongly represented in the positive estimates.

To be fair, these moderate-range differences in political leanings are not great. Pro-immigration teams were slightly positive overall, while anti-immigration teams were somewhat opposed. However, when it comes to a number that can make a headline, one of those tail values shows a much greater bias. The anti-immigration group has a thicker negative tail (more strongly negative estimates). The pro-immigration group has a thicker positive tail (more strongly positive estimates).

To go beyond descriptive patterns, the researchers ran a simple regression that linked each AME estimate to the team’s ideological position, controlling for factors such as team size, experience, and academic discipline. These controls matter because training and collaboration styles can influence both beliefs and analytic habits. Even after adjustment, ideology remained predictive: anti-immigration teams produced more negative estimates, pro-immigration teams more positive ones, and moderates clustered closer to zero.

The graph shows that even after statistical adjustment, ideological grouping predicts the direction of the estimated result. Anti-immigration teams were most negative, pro-immigration teams were most positive, and moderate teams fell closer to zero.

The graph shows that even after statistical adjustment, ideological grouping predicts the direction of the estimated result. Anti-immigration teams were most negative, pro-immigration teams were most positive, and moderate teams fell closer to zero.

Bias Enters Without Intent

Now, before we go off to gather our pitchforks and light our torches in a march on the castle walls of academia, the researchers considered whether there were underlying factors, other than evil intent to misdirect, at play. It is not the case that ideology directly changes estimates; the source of bias is more nuanced.

Even with identical data and questions, researchers must navigate a maze of reasonable analytic decisions. The authors argue that ideological priors subtly guide researchers along different paths through that maze, producing systematically different results. Among more than 100 design choices, decisions about variable definitions, modeling strategies, geographic scope, and time frames accounted for much of the variation. From these, the authors assembled a menu of 58 distinct “research recipes” and asked a simple question: for each recipe, would the expected conclusion be positive or negative?

Teams at the ideological extremes tended to choose combinations of modeling decisions that generally lead to estimates consistent with their point of view. Anti-immigration teams were the only teams using specifications that produced the lowest expected AMEs. In contrast, Pro-immigration teams were the only teams using specifications that produced the highest expected AMEs. As it turns out, two-thirds of the differences in outcomes can be accounted for by those design choices. Bias need not be intentional, and it certainly is not magic; it lies in the choices we make in our analysis. There is no smoking gun, no single specification decision matters as much as a tendency to select particular clusters of choices.

Ideological Extremes Produce More Fragile Findings

In short, ideology appears to shape findings by nudging researchers toward different clusters of defensible design choices, producing much of the observed pro- versus anti-immigration gap. The authors also note that ideologically extreme teams tended to select specifications that received lower referee ratings than those favored by moderates. Because this experiment occurred in a low-stakes setting, the implications for policy-relevant research may be even more consequential. When careers, funding, or public decisions are on the line, limited time and attention can make it easier to stop once a belief-consistent result appears.

A Problem Far Bigger Than Immigration Research

The broader lesson is that any field dealing with complex data, multiple analytic pathways, and high interpretive flexibility faces the same vulnerability. Whether the topic is immigration, nutrition, environmental risk, or medical outcomes, different yet defensible choices about measurement, modeling, and scope can yield different conclusions. Bias does not usually arrive as a lie. More often, it emerges as a preference-guided route through a maze of choices, with the greatest distortion appearing at the extremes—where findings are most publishable and politically advantageous.

The most promising response is a mix of institutional counterweights and public literacy. A structured red-team approach—where an independent group stress-tests assumptions, reruns analyses with alternative specifications, and actively searches for fragility—can make policy decisions more robust by forcing conclusions to survive credible disagreement. For science-curious citizens, the toolkit is simpler: ask whether findings hold across multiple models or datasets, whether uncertainty and limitations are acknowledged, whether effect sizes are meaningful rather than merely “significant,” and whether independent teams have reproduced the result. Above all, treat any single study—especially one that neatly fits a political narrative—as a starting point, not a verdict.

Source: Ideological bias in the production of research findings Science Advances DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adz7173