The question of the day:

Which is trendier? Microplastics or microbiomes?

Hard to say. According to current research, microplastics are found everywhere in your body — your blood, your lungs, your placenta, eyebrows… Meanwhile, your microbiome — the bacterial community in your gut — is credited with governing pretty much every function of every lifeform on Earth, including your health and mood, your credit score, and your choice of car interiors.

Which wins? Let’s call it a grant-grabbing tie.

Today, we’ll look at a study featuring some genuinely clever science — genetic engineering plus a dose of chemistry — that could literally put a dent in microplastics, regardless of whether they’re a major health threat or just the latest environmental boogeyman.

Teaching Algae to Ooze Limonene (and smell good)

Professor Susie Dai of Texas A&M University and colleagues recently published a study in Nature Communications demonstrating that common algae can be “taught” through genetic manipulation to produce a very pleasant chemical (more on this later) called limonene — and that this limonene-enriched algae has just the right properties to soak up microplastics without using harsh chemicals or elaborate filtration systems.

And it smells nice.

How did they do this?

Researchers inserted the limonene synthase gene into a precise spot in the cyanobacterium’s DNA, enabling the cell to produce limonene at very high levels.

The molecular details are a nightmare for chemists. They involve transcriptional regulation, ribosomes, DNA polymerase, and other topics that send us reaching for the Rolaids.

So let’s keep it simple:

- They inserted a limonene-making gene into the algae’s DNA.

- This makes the algae crank out tons of limonene, which is probably against union rules.

- Where do such genes come from? Beats me. The Gap?

Why Limonene?

There are plenty of reasons why it's a good choice. Let's look at some of its properties (Figure 1).

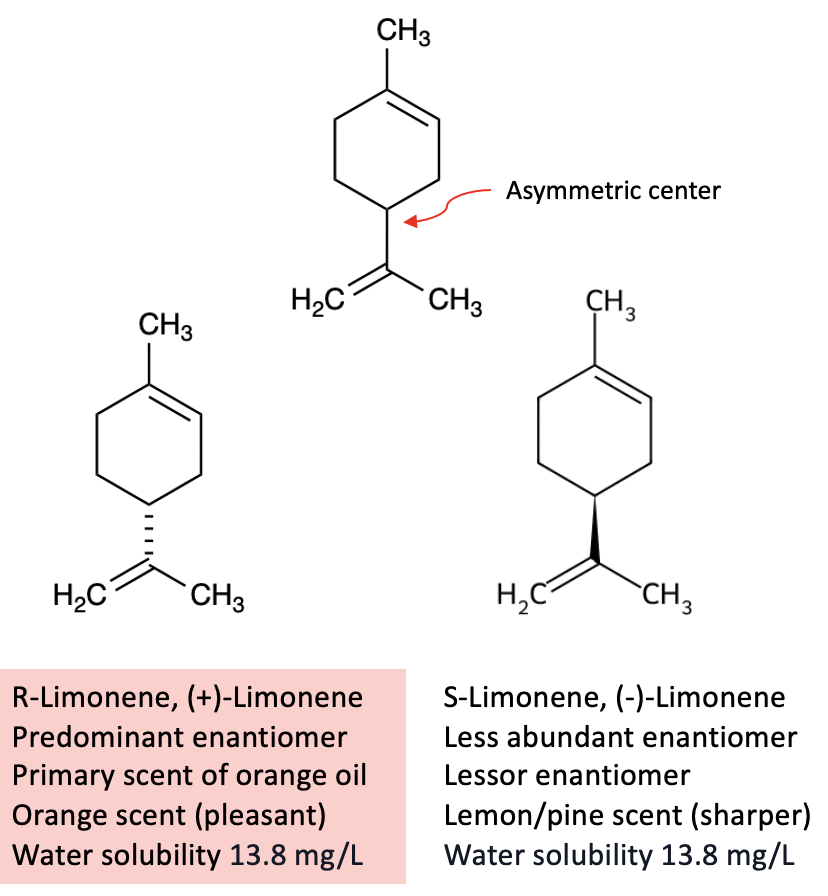

Figure 1. Selected properties of limonene. Although the two enantiomers differ in scent (orange vs. lemon), they have identical physical properties, including low water solubility. That’s no coincidence: enantiomers always have identical boiling points, melting points, and solubilities.

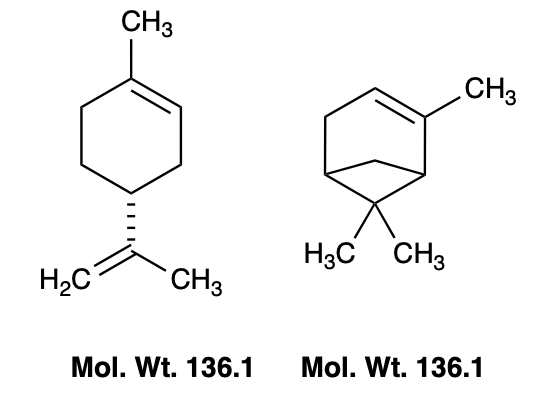

As a hydrocarbon, limonene behaves a lot like a pleasant paint thinner: it barely dissolves in water but readily dissolves oils, resins, and other nonpolar gunk — including some plastics. Another well-known nonpolar solvent is turpentine, a terpene mixture primarily composed of alpha-pinene. The similarity between the two molecules should be obvious (Figure 2).

Figure 2. R-limonene (left) and alpha-pinene (right) are naturally occurring terpene hydrocarbons. Both are nonpolar oily liquids that dissolve grease, paints, and resins.

How this works

Limonene is the key to how the system functions. The engineered cyanobacteria are grown in closed photobioreactors or managed ponds, where they use light and CO₂ to grow. Because they’ve been modified to produce large amounts of limonene, their cell surfaces become more hydrophobic.

When microplastic-contaminated water is introduced, chemistry takes over. Plastics are hydrophobic too, so the limonene-coated cells and plastic particles naturally stick together. As they bind, aggregates form, and once those clumps become large enough, gravity does the rest. Within about an hour, much of the microplastic settles to the bottom as sediment.

That sediment — a mixture of algal biomass and captured plastic — is harvested. The clarified water can then be discharged or further treated, depending on regulatory requirements. Since the algae are grown in reactors or managed ponds, they aren’t released into natural waterways; they’re cultivated, used, and removed.

Instead of filtering microscopic particles out of water — an expensive, clog-prone process — this approach makes the plastic stick to something larger and let it sink.

It’s surface chemistry plus synthetic biology, applied with unusual practicality.

Very clever, indeed.

Source: Remediation and upcycling of microplastics by algae with wastewater nutrient removal and bioproduction potential. Nature Communications DOI:10.1038/s41467-025-67543-5