The Body’s Internal Clock

There is recognition that long before the invention of clocks, time ruled our internal selves through circadian rhythms, the metronome of our daily behavior and metabolism. Emerging from cellular chemical clocks within our hypothalamus and peripheral tissue, circadian rhythms, like the moon’s effect on the tides, control the ebb and flow of our physiological responses. The scientific findings that metabolic processes exhibit diurnal variation lend credence to the panoply of diets centered on a specific “eating window,” or the heuristic, "Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper."

Our circadian rhythms are entrained or “reset” in the hypothalamus by our experience of sunrise and sunset and in the peripheral clocks of the liver, gut, and pancreas by our food intake. Much as we have desynchronized from the external light-dark cycle with artificial lighting, our internal metabolic clocks have become desynchronized by a food environment that allows us to eat and graze whenever we wish. A new study in eBiomedicine investigates

“the link between the eating timing pattern relative to individual clock and glucose homeostasis [exploring] the contribution of genetic and environmental factors to eating timing parameters.”

From a more personal perspective, how does this affect me; the goal was to uncover which of our eating behaviors might be changeable and which are hardwired.

The Study: Eating Patterns and Internal Time

Ninety-two adult DNA-identified twins were recruited from the German NUtriGenomic Analysis in Twins (NUGAT) cohort. Mean age was 31.9 years, a “healthy” BMI of 22.8, compared to a US average “overweight” of 29, all without diabetes. There were 32 pairs of “identical,” monozygotic (MZ) twins, and 12 pairs of fraternal or dizygotic (DZ) twins. [1] Participants underwent metabolic phenotyping that included the usual anthropometric and physiological measurements, including a standard glucose tolerance test and completed food records, “noting the start and end of each eating event, the amount and kind of consumed food, for five consecutive days.”

Eating “events” involve at least 50 calories, with a gap of at least 15 minutes between events. The eating window was defined as the difference between the first and last eating events, and a caloric midpoint was calculated for the time when 50% of calories had been consumed. Participants consumed 4.75 meals or snacks daily, with the first at 9:15 AM and the last at 8:12 PM, creating a nearly 12-hour eating window. Energy intake for the first meal was roughly 25% of the daily total, the last meal was about 33%, and the caloric midpoint occurred at 3:51 PM. Longer eating windows were associated with more caloric intake, although first and last meals tended to be smaller.

Chronotype and Caloric Timing

Individual circadian rhythms were based on questionnaire data on sleep cycles, capturing when participants felt ready to sleep, when they awoke, both on workdays and free days. The midpoint in sleep, the MSFsc, was calculated, correcting for any “sleep-debt” to define individual chronotypes. Early types slept the least, with an MSFsc of less than 4 hours, while late types slept more than 5 hours. Thirty-eight participants were early types, 27 late, and 24 were intermediate chronotypes. The mean onset of sleep was 11:15 PM, with awakening at 7:28 AM, resulting in a sleep duration of nearly 8 hours.

The researchers defined the interval between an individual’s midpoint of sleep, the MSFsc, and the “clock time” when 50% of the daily calories had been consumed, the caloric midpoint, as the circadian time of caloric midpoint, CCM. A high CCM signifies an earlier caloric midpoint relative to one’s circadian rhythm.

What the Data Revealed

The CCM was the most significant factor linked to health outcomes, providing more meaningful and stronger associations with glycemic and anthropometric traits compared to examining standard clock times alone. Eating later in relation to your body clock was significantly linked to poorer insulin sensitivity, greater insulin resistance, and higher fasting insulin levels. Adjusting for gender, age, energy intake, and sleep duration had no impact, suggesting that the timing of meals was an independent factor. It seems that individuals consuming more calories earlier in their CCM had better “glucose tolerance.” [2]

Eating later was consistently associated with higher BMI and waist circumference. Those results were not affected by adjustments for gender, age, energy intake, and sleep duration. Eating later has previously been shown to be associated with less effective weight loss. Studies have indicated that melatonin, which rises as the evening progresses, may enhance insulin resistance, a finding that supports this observation.

Genetics Plays a Role

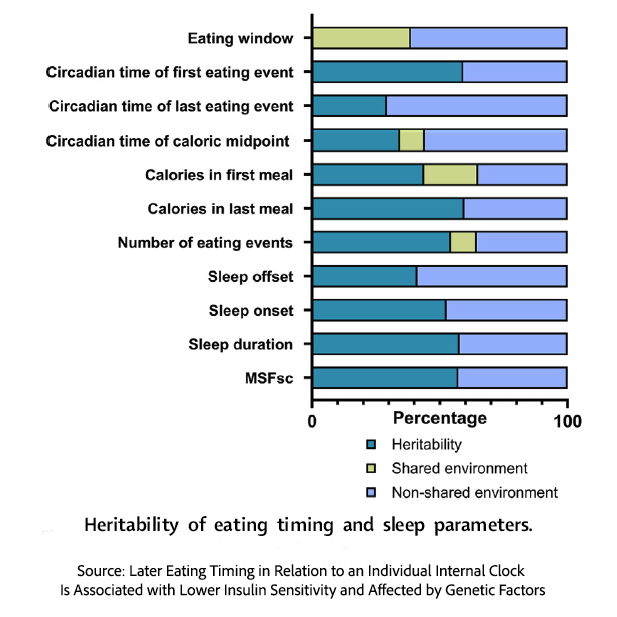

"All eating timing components showed high or moderate heritability."

High heritability, defined as greater than 50%, was found for the circadian timing of the first “eating event,” the number of those events, and the percentage of energy consumed in the last daily meal. There was a similar genetic influence on the sleep parameters used to define individual circadian rhythms. In noting that this genetic influence may make shifting meal times more challenging, it is essential to remember that, despite this being a twin study, environmental and cultural factors, such as when and how we eat, can be transmitted across generations.

It appears that adjusting your central caloric intake to earlier circadian times may improve glucose metabolism and offer a potentially modifiable component to healthier eating habits. Interventions might be more effective targeting the caloric midpoint or last meal timing due to their lower heritability compared to the first meal. Personalizing the timing, based on your chronotype, may make dieting easier by aligning with your circadian biorhythm. As it turns out, "Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper” has scientific underpinnings.

As with all studies, there are limitations. The eating and sleeping data are self-reported, the cohort young and lean, and the sample size small. While all reduce the generalizability of the findings, they do not mitigate that:

"[The] study revealed that the eating timing is associated with glucose homeostasis and shows significant genetic influences. … Shifting the main calorie intake to earlier circadian times may improve glucose metabolism, but the high heritability of meal timing components suggests that genetic predispositions could influence the feasibility and effectiveness of such interventions."

This study adds compelling evidence to the idea that when we eat matters just as much as what we eat, and that our circadian clock control should be the ultimate timekeeper of our meals. Some of the irreducibility of prior studies may be due to a lack of adjustment for individual chronotropic metabolic shifts. It is also suggests that those advocating and pursuing diets based on six or eight-hour “eating windows” might place their window in relationship to their sleep cycle. The study opens the door to personalized meal-timing strategies that account for biological rhythms, providing a practical and scientifically grounded approach to promoting metabolic health. In other words, Boomers’ “early bird” dinner may have been metabolically wiser than you, or they, thought.

[1] There was one individual in the MZ group who did not have a pair.

[2] The researchers also found that earlier meals were positively associated with the pancreas’s beta-cells, the cells responsible for insulin production, to compensate for insulin resistance, suggesting a protective effect against diabetes for those who eat early.

Source: Later Eating Timing in Relation to an Individual Internal Clock Is Associated with Lower Insulin Sensitivity and Affected by Genetic Factors eBiomedicine DOI: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105737