You say tomato, I say potato

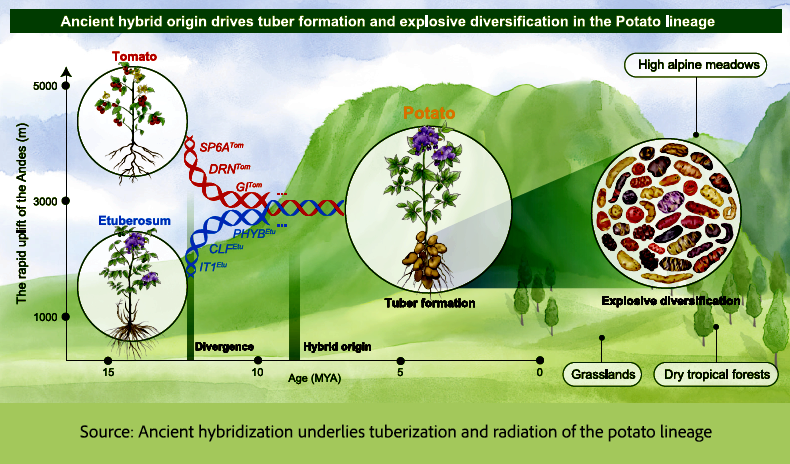

The potato, along with wheat, rice, and maize, provides 80% of our global caloric intake. The humble potato, long seen as the starchy staple of famines and fries, originates in the Andes, and its parental heritage has, till now, been unclear. In a 23andMe-like moment, researchers have discovered that the potato is the result of a mixed marriage. This was no scientifically arranged union, but a serendipitous coming together of the right genes in the right geological moment — a natural shotgun wedding against the backdrop of a rapidly rising Andes. The result was a genetic mosaic that gave us not just a new plant, but a new organ, the tuber, that would go on to feed civilizations.

Like a blended family of royal houses with contrasting virtues, the potato is the child of a union between two wildly different but genetically compatible lineages: the tomato clan, bearing no tubers but rich in sunlight-sensing genes, and the etuberosum line, with rhizomes and reproductive adaptability but none of the spud glory. Let’s consider the parents.

Meet the In-laws: Parental lineages

The tomato lineage (family) comprises 17 cultivated and wild species, all of which are descendants of a common ancestor, referred to as a monophyletic lineage. Like us, they are genetically diploids, possessing two sets of chromosomes. Roughly a third are “self-compatible,” able to self-pollinate. While tomatoes have underground stems (roots) that capture nutrients and water, they do not have specialized subterranean horizontal offshoots, in the form of tubers or rhizomes.

The Etuberosum family is far smaller, with three distinct species. Like tomatoes, they share a common ancestor and are diploids; however, they are more self-compatible (self-pollinating). But unlike tomatoes, they have rhizomes, which serve as a site for nutrient storage and, more importantly to our story, self-reproduction.

The hybrid child resulting from the chance encounter of these two families possesses a stable mix of genetic material from both lineages, still observed in all modern potato species.

Of course, before this marriage of chance or convenience, both plants had found genetic ways to survive and thrive in their environment, through "Positively Selected Genes" (PSGs), variants produced by natural selection. The early potato had possibly 229 PSGs from Euberosum and 269 PSGs from Tomato to inherit. And because this was a mixed marriage, the potato did not inherit one version of these genes, but a mosaic of “highly divergent parental genes” not present in either parent.

Tubers: A parental gift

That mosaic of genes allowed a pathway for the potatoes’ “key innovation,” the tuber. It was as if the best "parts" from each parent were combined to build this new, essential organ. The tomato family contributed three unique genes. A gene called Gigantea, which helps the plant sense light, and is key to knowing when to start forming tubers. Self-pruning 6a, which acts like a switch to turn on tuber growth, and Dornronschen, which manages where and how the specialized stem creating the tuber appears. The Etuberosum side of the family contributed another light-sensing gene, Phytochrome B, which accelerates the onset of tuber growth, and It1, which plays a significant role in guiding tuber growth.

Horses, Donkeys, and Mules

Mixed marriages, in nature, come with difficulties in reproducing after the formation of a zygote (fertilized egg). Postzygotic reproductive isolation leads to lower overall fertility and breakdown in the hybrid – it’s nature’s form of a marital separation. It is why when crossing a horse with a donkey, the offspring, the mule, is sterile.

However, potatoes’ inheritance, their superpower, was the trait of tuberization. Tubers store water and carbohydrates, providing a backup source of nutrition when times are tough. More crucially, tubers allow for asexual reproduction, bypassing the vagaries of reproductive isolation, providing a stable mechanism for "stabilization of beneficial hybrid gene combinations and recombinations," allowing the early hybrid lineages to persist and establish themselves, even if sexual reproduction was initially challenging.

Etuberosum had one more genetic gift for its potato child, which would serve it well in its new home. To understand that gift, we must consider the changing nature of the potato-child’s home. That shotgun wedding occurred eight to nine million years ago, just as the potato’s Andean home was severely altered by the Andean uplift, an ongoing orogeny, mountain-building, which provided the potato with an entirely new environment to explore. The uplift was a pivotal environmental factor that significantly influenced the evolutionary trajectory and diversification of our story’s hero. It provided the ecological opportunities and selective forces that made the potato’s genetic mosaic highly advantageous

The shifting of tectonic plates resulted in the formation of new habitats at higher elevations and in colder climates. The Eteberosum’s genetic gift was a more robust response to cold and cold-drought stresses, a greater ability for cold adaptation, which the tuber, as an underground storage organ, is inherently suited to support. As a result, potatoes' “niche breadth,” the range of environmental conditions or ecological habitats that a species or lineage is capable of occupying, is twice that of parent tomato and threefold that of parent Etuberosum.

The marriage between tomato and etuberosum may have been improbable, but it was undeniably fruitful. Their hybrid child inherited the best of both worlds: light-sensing acuity, reproductive flexibility, and the innovation of the tuber, nature’s underground pantry. This fusion of divergent genes set the stage for the potato’s global success, expanding its ecological range and evolutionary potential. In the end, it wasn’t an arranged marriage, but a natural one — a union of chance that changed human history.

Source: Ancient hybridization underlies tuberization and radiation of the potato lineage Cell DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.06.034