By any measure, developing new analgesics has been slow, difficult, and largely disappointing. [1] Despite repeated attempts to improve or replace opioids, there is still no reliable drug for moderate-to-severe pain without major drawbacks. Now, groundbreaking work from Dr. Richmond Sarpong at UC Berkeley and colleagues may change that.

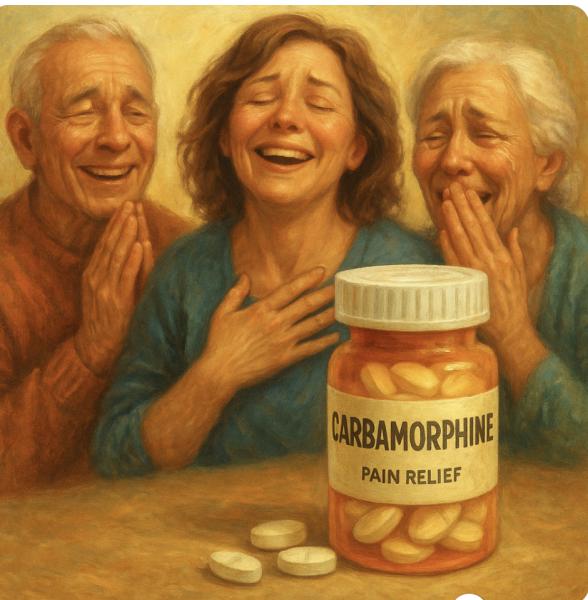

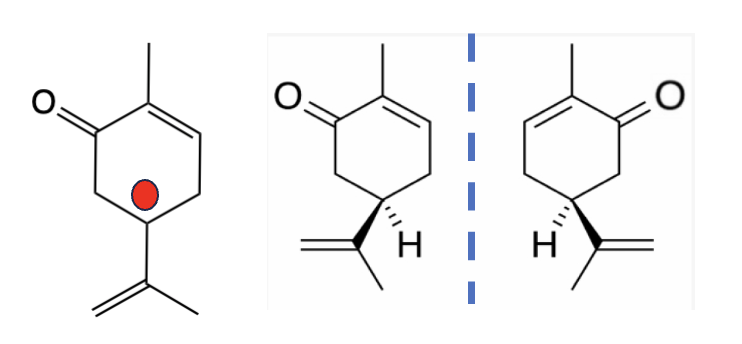

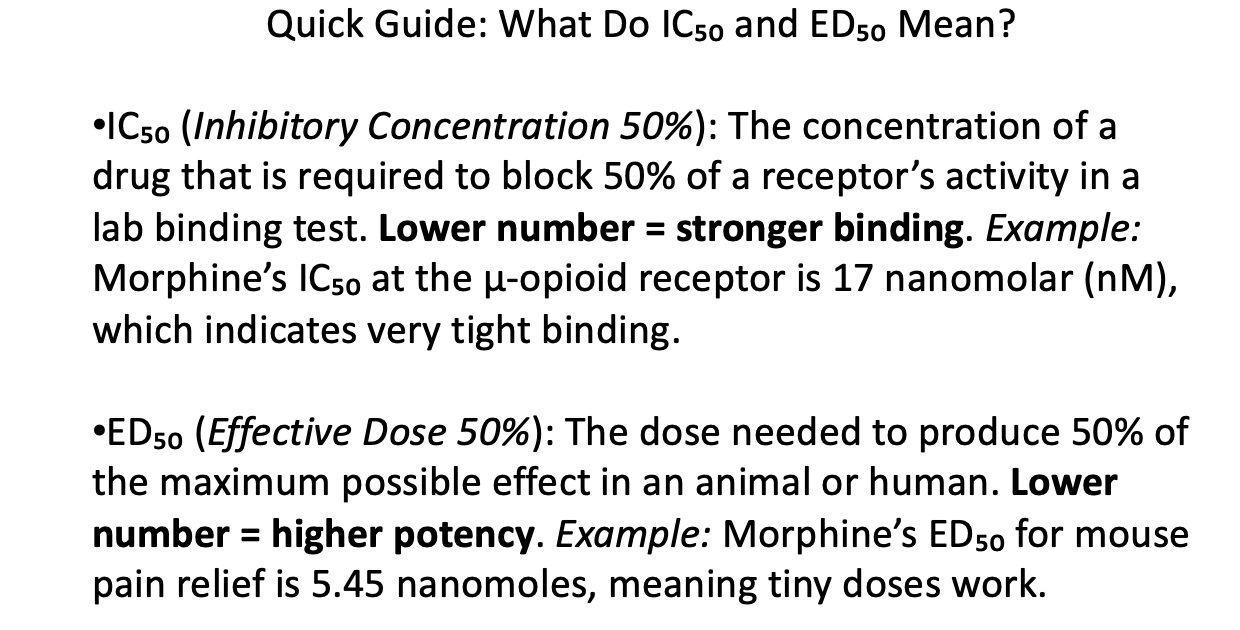

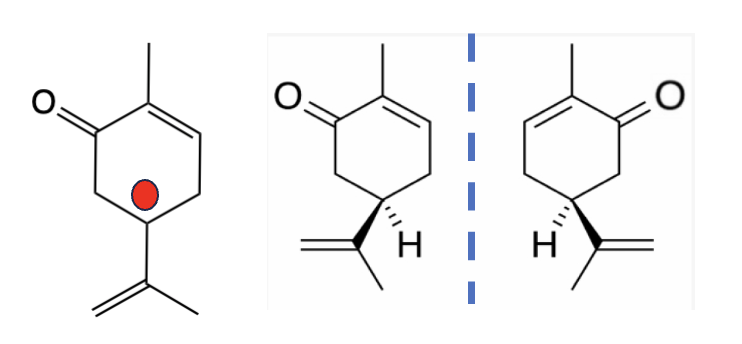

Sarpong took advantage of a tried and true medicinal chemistry strategy called bioisosterism [2] (a fine Scrabble word) to design and synthesize the first-ever morphine analog in which a carbon atom replaces oxygen in one of the rings in the morphine scaffold (Figure 1).

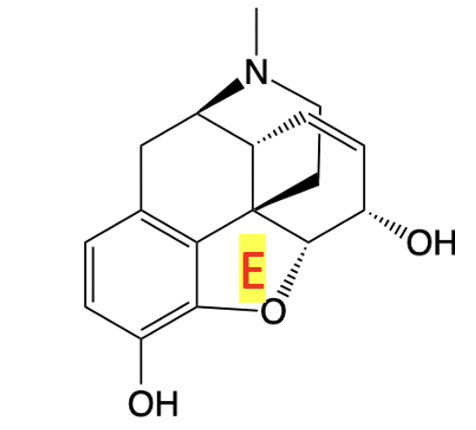

Figure 1. Replacement of the ring oxygen in morphine by carbon (yellow arrows) gives carbamorphine. The remainder of both molecules is identical.

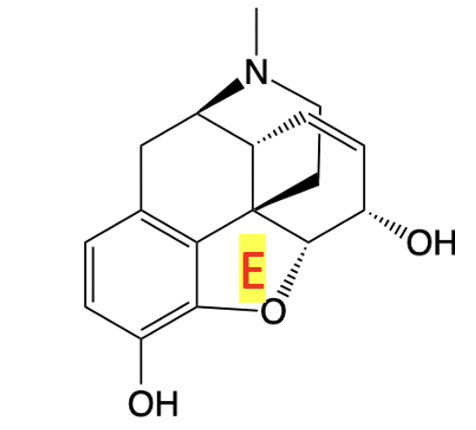

"Here, we show that a single heavy atom replacement in the morphine core structure (O to CH2 exchange in the E-ring) prepared through a 15-step total synthesis displays a different pharmacological profile."

Why is this a big deal?

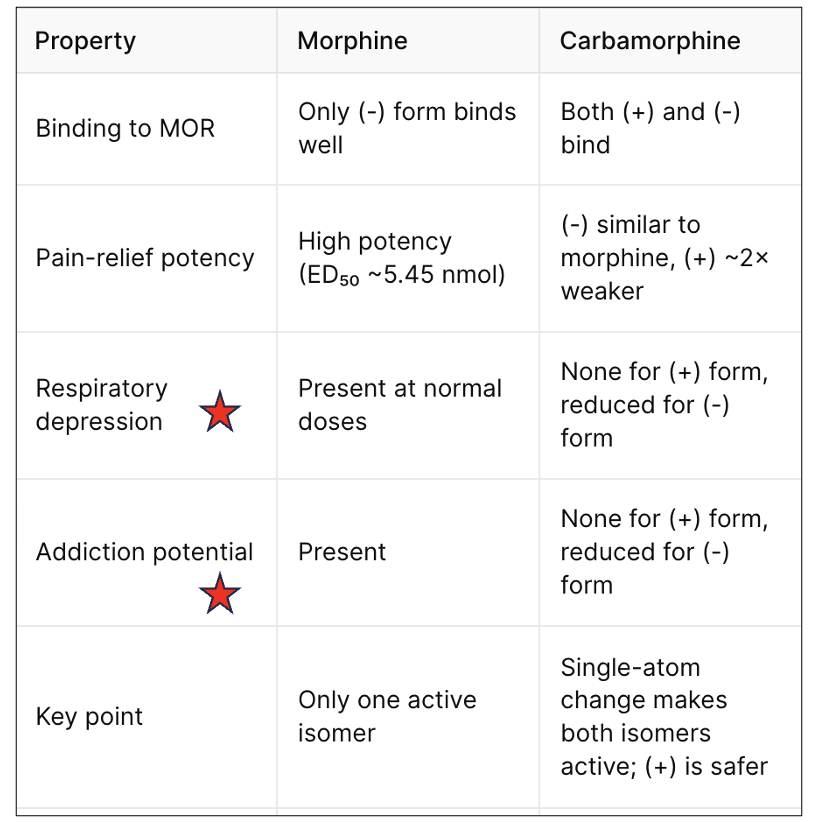

That quote above understates the significance of this discovery, and not by a little. In short, here are some properties of carbamorphine as compared to morphine as reported in the Sarpong paper:

- Retention of µ-opioid receptor (MOR) selectivity and analgesic effect

- Reduced respiratory depression in mice

- Lower addiction potential, as demonstrated by a mouse behavior test

The potential here is mind-blowing. While keeping in mind that animal models of a drug may or may not be predictive of what the drug does when tested in humans, imagine a modified opioid with fewer of the most serious side effects, that is less addictive and retains its analgesic properties. Consider the benefits of such a drug, especially for pain patients who continue to have more and more trouble getting hold of the meds they need.

That said, it won’t be easy. Animal models are notoriously poor predictors of clinical success—a well-known barrier in early-stage drug discovery. Carbamorphine remains in the very early (preclinical) phase, where promising molecules often fail to make it past the starting line. The earlier in the process, the higher the likelihood of failure later on.

However, there's another hurdle in carbamorphine’s path. Unlike semisynthetic opioids, which are easily derived from poppy-based compounds, there’s no shortcut to carbamorphine; it can’t be made from anything that grows in nature. In other words, it really doesn’t grow on trees. Producing it requires a complex, multi-step synthetic route from scratch.

Organic Synthesis: Simple or Nightmarish

-

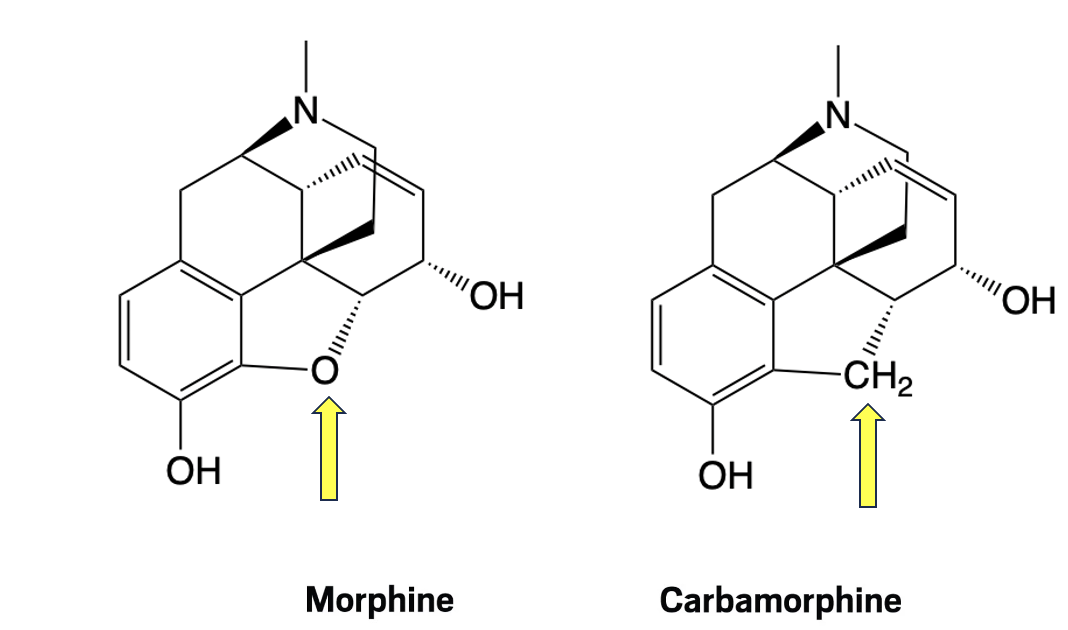

Simple: Morphine ---> Heroin

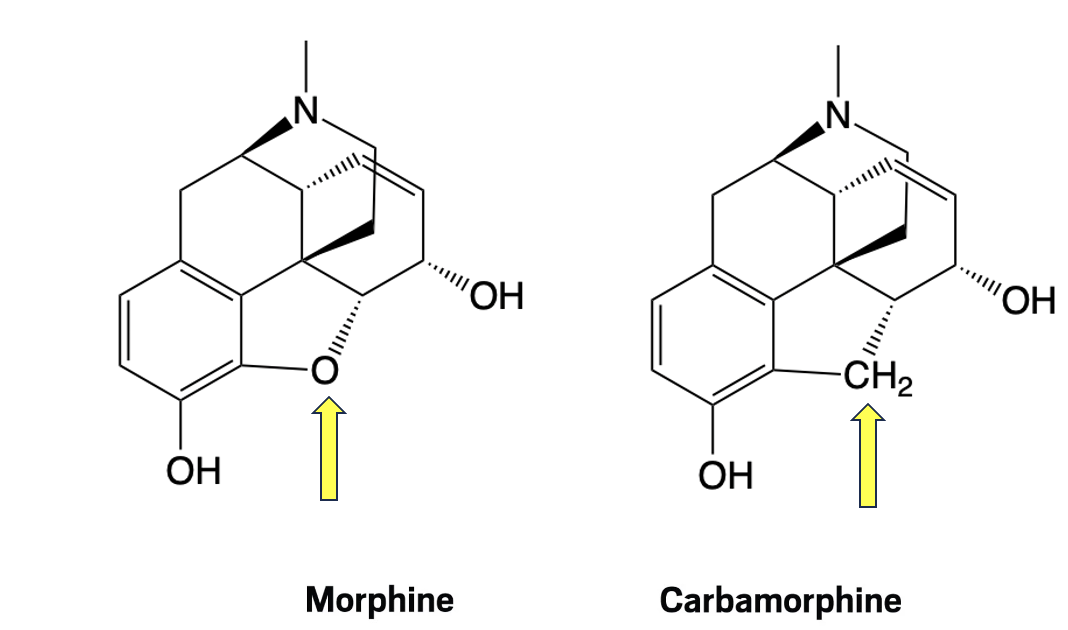

Sometimes, modification of a drug to form a different analog is a trivial one-step process that can be accomplished in a few minutes with a few common chemicals. Nothing exemplifies this better than the conversion of morphine into heroin, which is accomplished in one very simple synthetic step as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The conversion of morphine to heroin. As easy as it gets.

As shown in Figure 2, both hydroxyl groups on morphine are acetylated using acetic anhydride—a cheap, common lab reagent—forming heroin (a.k.a. diacetylmorphine). The reaction is remarkably clean: no byproducts, and nearly quantitative. In organic synthesis, we call this a “100% yield” when the amount of product matches the theoretical maximum. That’s rare, so for illustration, let’s assume a 95% yield—still excellent. Starting with 10 grams of morphine, a chemist would end up with 12.3 grams of heroin, 95% of the maximum possible. (And no, matter isn’t being created. The extra mass comes from the two new acetyl groups.)

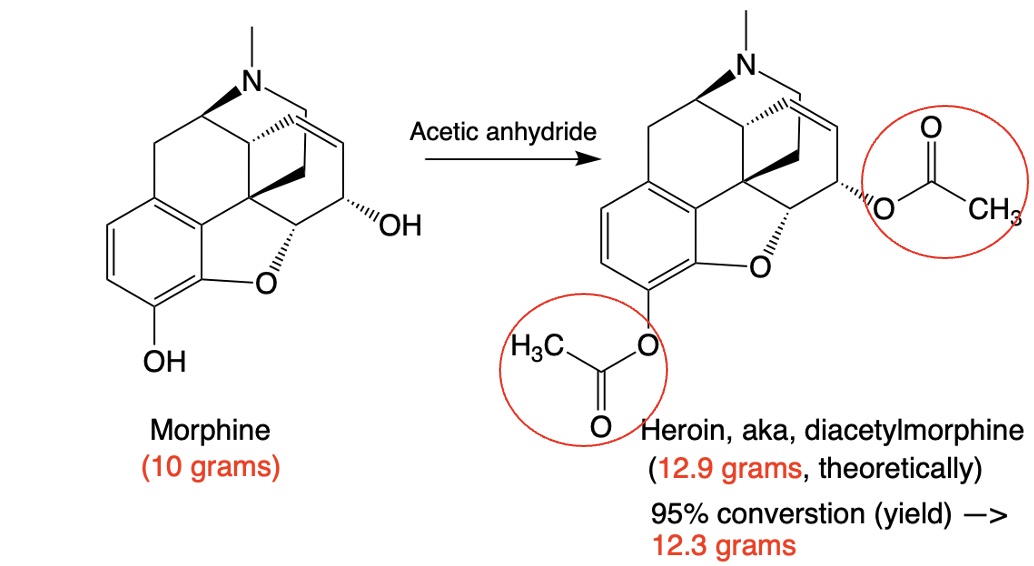

2. Not so simple: Morphine ---> Carbamorphine

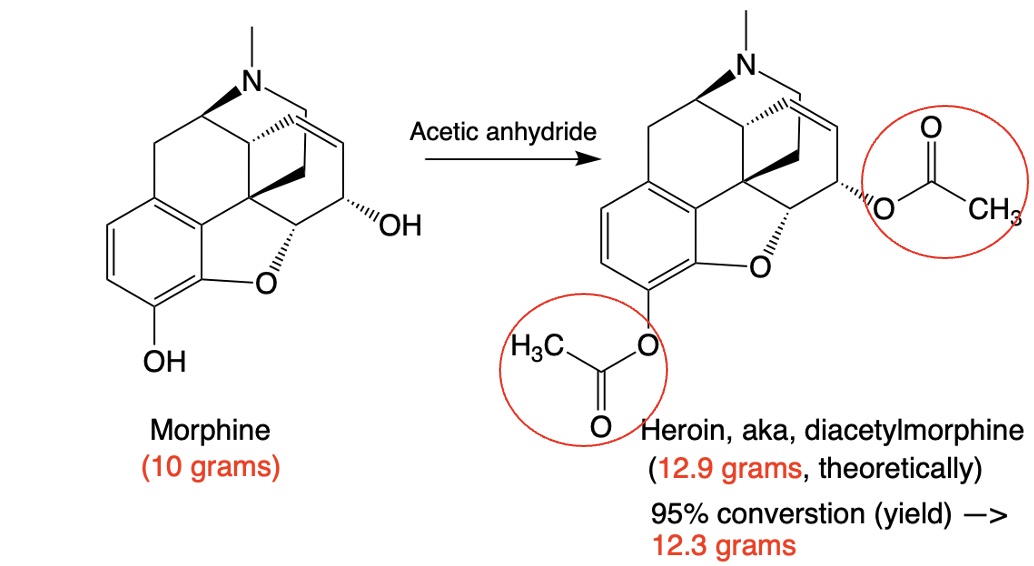

At first glance, Figure 1 might lead one to assume that carbamorphine could be easily synthesized from morphine, given their structural similarity. However, this assumption would be incorrect. The synthesis of carbamorphine is not a straightforward modification of morphine. It requires a fully de novo, 15-step route that took approximately 18 months to complete. But structural resemblance doesn’t make a compound easy to make, as Figure 3 makes painfully clear.

Figure 3. Even when they've developed a very efficient (clean reactions, few byproducts) 15-step synthesis, chemists almost always take a beating when it comes to obtaining the final product.

This is why replacing that simple oxygen-to-carbon transformation is very far from simple. It requires a total synthesis, starting with a starting material called indanone, which looks nothing like morphine. Don't worry; I'm not going to torture you with a synthetic scheme, just a little about the difficulty of making large quantities of anything using a 15-step synthesis like the Sarpong group did.

Now, imagine a 15-step synthesis where each step has a 75% yield, which is damn good. How much material will remain at the end? It’s like compound interest in reverse: you multiply 0.75 by itself 15 times (0.75 × 0.75 × …), which comes to just 1.3% overall yield, about 0.13 grams from the 10 grams you started with, roughly the weight of five grains of rice. Even though this number may horrify you, it is still considered a very good average yield in complex synthesis. Nonetheless, after almost two years of work, that’s all the chemists have to show for it, the kind of result that sends post-docs job-hunting at Home Depot, to therapists, or both.

The group somehow managed an average yield of 84% per step (amazing). Even so, they would still end up 18 months later with only about 0.3 grams from the 10 grams they started with, roughly the weight of a single paperclip or a small raisin — barely enough for animal efficacy and toxicity studies.

Biology time: Binding, analgesia, pain relief, and side effects. And an enormous discovery.

Despite their structural similarities, it is not a simple task to compare morphine and carbamorphine; this requires understanding how they bind to key receptors, how strong that binding is, and what biological consequences follow.

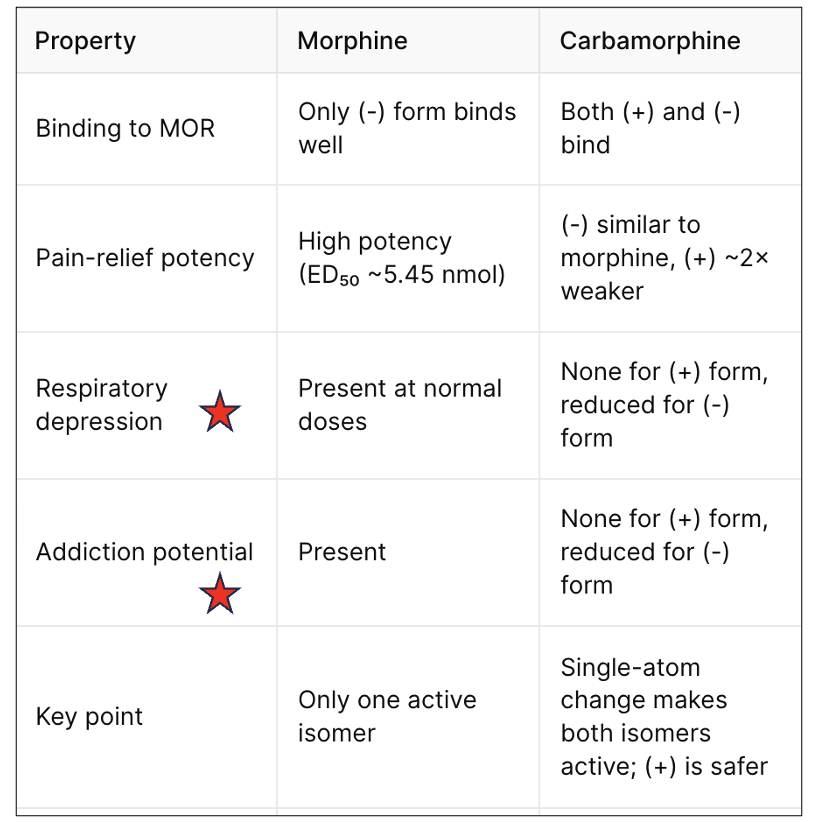

Before we dive into dreaded stereochemistry, here’s the headline: Carbamorphine appears to work in a way morphine never could. In morphine, only one version of the molecule — one of its two mirror-image forms — works to relieve pain. The other does nothing. But in carbamorphine, both versions work: one is almost as strong as morphine, the other about half as potent — and that “second” version seems to avoid dangerous side effects like respiratory depression and addiction risk. More on this below.

Enantiomers (sorry)

If there's one thing that drives organic chemistry students absolutely nuts, it's stereochemistry. I'll try to make this as painless as possible. Stereochemistry is the study of how the 3-D shape of asymmetrical molecules (the way their atoms are arranged in space) affects their properties and behavior.

I've

written about this before. An essential oil called carvone is a mixture of two seemingly identical chemicals that are mirror images (Figure 4). They can be separated; one smells like caraway and the other spearmint. Why is this important?

Figure 4. (Left) Carvone, drawn flat, ignoring the asymmetric carbon (red circle), appears to be a single chemical. But when drawn in 3-D (this is very hard for non-chemists to understand), the two different isomers (enantiomers) become apparent.

What does this have to do with carbamorphine?

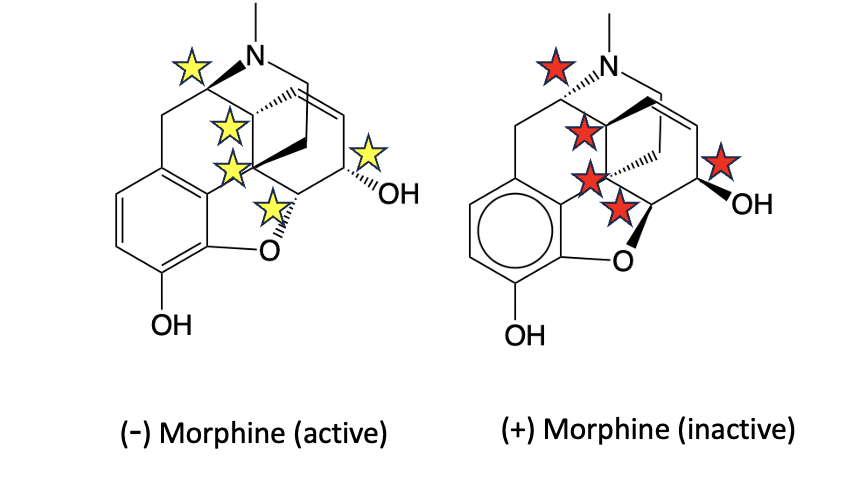

Most natural products (~80%) are asymmetrical and therefore can exist in two different forms (mirror images, also known as enantiomers) commonly referred to as the (+) and (-) isomers. Almost without exception, when a drug or natural product is asymmetrical, one of the two isomers is responsible for all of the biological activity. In contrast, the other isomer is dead weight. Sometimes worse. [4]

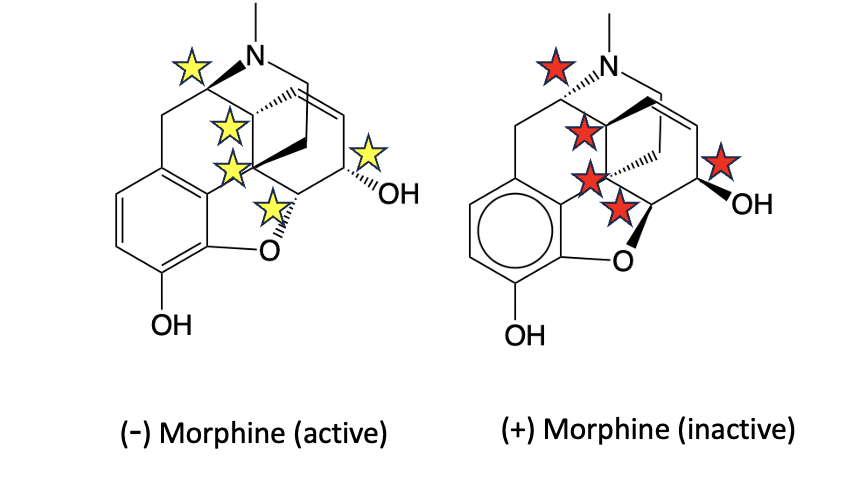

Like carvone, morphine consists of two isomers (Figure 5). One, the (-) isomer (don't ask about the minus sign) is responsible for all biological effects of the drug. The (+) isomer is completely inactive; it does not bind to MOR receptors. This kind of mirror-image selectivity is typical in natural products. 3D shape matters — more than you'd think.

Figure 5. (-) Morphine (left) and its (+) "sibling" are mirror images of each other. The yellow and red stars indicate the five asymmetric carbon atoms in the molecule. These carbon atoms are mirror images of each other. Non-chemists – don't try to figure this out. I'm begging you.

The reason this study is remarkable

I didn't drag you through the detritus of stereochemistry for no reason. Carbamorphine breaks the rules, as measured by its potency and pharmacological properties. (For those of you not familiar with how drug potency is measured, see Note 5.)

Because (+) morphine is inactive (it doesn't fit the MOR receptor), it cannot cause the benefits (analgesia) or side effects associated with opioids. But with carbamorphine, both enantiomers are analgesic, raising the possibility of a morphine-like drug without morphine-like side effects – a modified opioid with built-in advantages nature never gave us.

The group discovered that both enantiomers of carbamorphine are biologically active. No one could have predicted this astounding finding in advance. The authors note:

"This result was unexpected given the established stereochemical requirements for morphinan ligands." - Sarpong, et. al.

Why is this so important?

The activity of both enantiomers at MOR was unanticipated and suggests that O-to-CH₂ replacement in the E-ring alters the binding pose in a way that relaxes the strict stereochemical preference of the receptor. [See Figure 6]

Figure 6: The chemical structure of morphine with the E-ring indicated.

In other words, the "simple" O --> C replacement does something unexpected; it changes the way that carbamorphine binds to opioid receptors, and this opens the possibility of novel opioid drugs that could rewrite pharmacology textbooks.

The results speak for themselves.

In morphine, only one mirror-image form — the (–) isomer — binds to the µ-opioid receptor (MOR), delivering strong pain relief but also triggering the same signaling pathways (beyond the scope of this article) that cause respiratory depression and addiction. Its (+) isomer, by contrast, does not bind the receptor and has no effect of any kind.

It bears repeating: Carbamorphine turns the long-standing “one active isomer” rule on its head. Here, both mirror-image forms interact with the µ-opioid receptor — the (–) isomer delivering potency close to morphine, and the (+) isomer bringing solid analgesia while dodging the molecular pathways tied to respiratory depression and addiction (also beyond the scope of this article). It’s as if the molecule has a built-in “good twin” that keeps the pain relief but leaves the danger behind.

Should everything hold up, in the annals of medicinal chemistry, this discovery should be filed under "OMG."

Activity in mice is critical. Carbamorphine passes.

In mice, this “safer” isomer caused no respiratory depression — even at ten times its effective dose — and also showed no signs of eliciting addictive behavior. A single-atom swap in morphine’s structure has turned a one-isomer drug into a two-isomer drug, and one of them might be a far better opioid. The side-by-side comparison in Table 1 distills the key pharmacological differences and potential clinical advantages of carbamorphine over morphine.

Table 1. Comparison of the binding, potency, and side effects of morphine compared to carbamorphine. The red stars indicate animal behavioral tests.

Bottom line

If carbamorphine’s early promise holds up in human trials, it could mark the first true leap forward in opioid pharmacology in...forever. The path ahead will be long, expensive, and absolutely loaded with opportunities for failure, but the concept is too important to ignore. By showing that a single-atom change can rewrite the rules of receptor binding and side effect profiles, Sarpong’s team has opened a door that medicinal chemists have been banging on for decades. Whether carbamorphine itself makes it to the clinic or inspires a better successor, it has already succeeded in proving that nature’s blueprint for morphine is not the final word.

NOTES:

[1] No, I am not ignoring Vertex's

Journavx. While it is about as potent as hydrocodone, one of the weaker commonly used opioids, Vertex uncovered a new mechanism for controlling pain – a huge accomplishment. Normally, this would lead to Vertex and other companies jumping all over this molecule, trying to improve it. But then this happened:

8/6/25: BAD NEWS: Vertex ran into a big wall in its efforts to develop VX-993 as a follow-up to Journavx. VX-993 failed to outperform placebo. Here's the press release. The company may drop the entire program.

[2] Bioisosteres are close analogs in which (usually) an atom of carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur is replaced by one of the others. This can have a profound effect on the properties of the new molecule, for example, potency, metabolic stability, solubility, etc.

[3] Almost without exception, nature makes only one of the two enantiomers.

[4] In rare cases, the “inactive” enantiomer of a drug isn’t harmless — it can cause serious harm. A well-known example is thalidomide, where one mirror-image form treated morning sickness but the other caused severe birth defects. Another is d-propranolol, the non-therapeutic mirror image of the active β-blocker, which does not help the heart but can still trigger unwanted side effects.

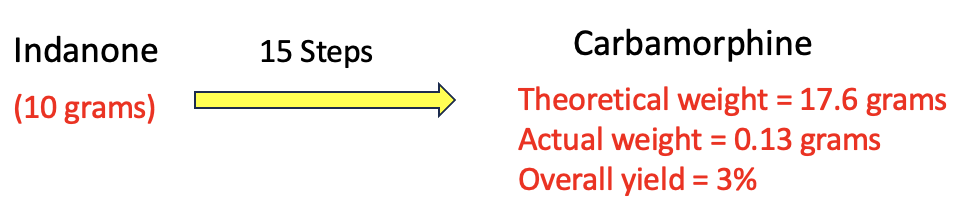

[5] Definitions of measures of potency:

How potency is measured in receptor binding assays (top) and in animals or humans.