HuffPost just published an interesting article titled "More And More People Suffer From 'Chemophobia' — And MAHA Is Partly To Blame." They're not kidding. As RFK Jr. continues to spread his nonsense about...pretty much everything, the terms "natural" and "organic" are being weaponized. Let's take a look at what "organic" really means. You may be surprised.

"Organic” may be one of the most confusing words in the English language. Most people have a vague idea of what it means, but few know the actual definition—because there isn’t just one. Chemistry has one definition, agriculture has another, and marketers… well, they make it up as they go.

The chemistry definition is unambiguous and clear-cut, at least most of the time. Let's start here.

THE CHEMICAL DEFINITION OF ORGANIC

In chemistry, the definition is based solely on chemical structure. With very few exceptions, a chemical is classified as organic if it contains at least one carbon atom, regardless of its source. This is why organic chemistry is referred to as "the chemistry of carbon."

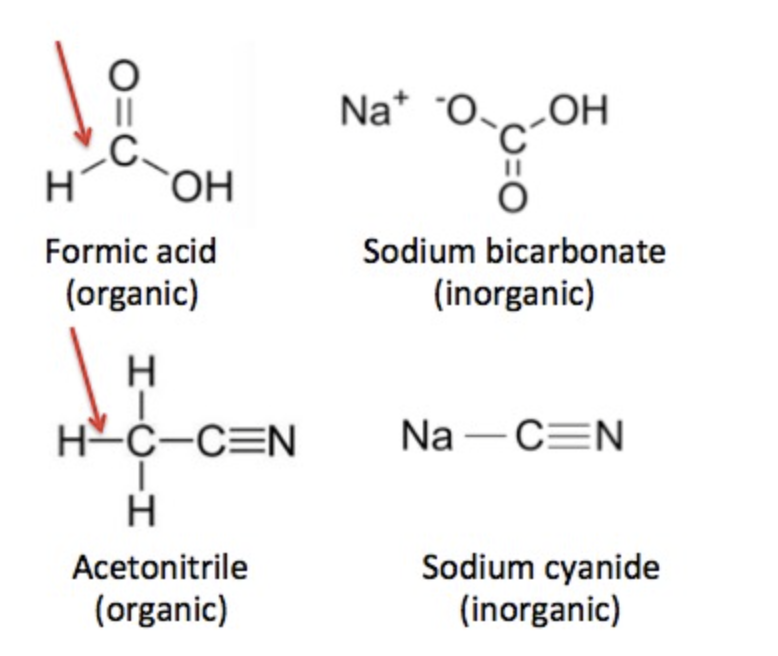

But there are exceptions. Carbon dioxide certainly contains an atom of carbon, but is classified as inorganic. Common inorganic chemicals include salt, ammonia, baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), and sulfuric acid. But, like carbon dioxide, baking soda also contains a carbon atom, yet is still classified as inorganic. What's going on? For a chemical to be organic, there is an additional requirement. A hydrogen atom must be chemically bound to a carbon atom. Figure 1 demonstrates examples of carbon-containing chemicals, some of which are organic and some that are not.

Figure 1. Organic vs. inorganic. Formic acid (top) is organic because it contains a carbon-hydrogen bond (red arrow), but sodium bicarbonate, although similar in structure, is inorganic because it lacks this bond. Acetonitrile and sodium cyanide (bottom) are another example of the same rule. Confused? You should be.

BUT...

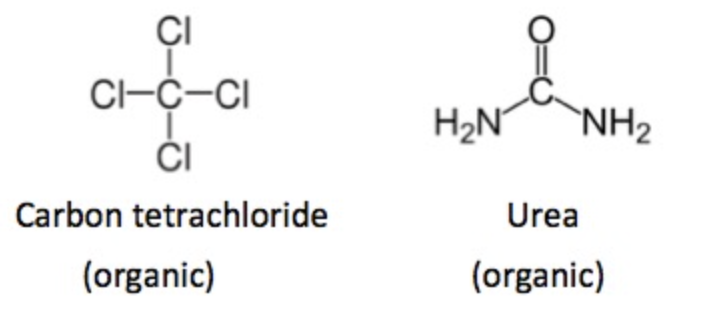

In organic chemistry, nothing is ever entirely straightforward. Both carbon tetrachloride and urea [1] (Figure 2) are considered organic, despite neither molecule containing a carbon-hydrogen bond or a carbon-carbon bond. These exceptions arise from historical precedent rather than a strict definition.

Figure 2. Both carbon tetrachloride and urea are generally considered to be organic. Neither chemical has a carbon-hydrogen bond. These are rare exceptions.

THE AGRICULTURAL DEFINITION OF ORGANIC

The agricultural definition of the term is entirely different from that of chemicals. It specifies which practices (including the use of chemicals) are permitted for food so that it can receive the USDA Certified Label. According to the USDA:

"Organic meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy products come from animals that are given no antibiotics or growth hormones. Organic food is produced without using most conventional pesticides; fertilizers made with synthetic ingredients or sewage sludge; bioengineering; or ionizing radiation."

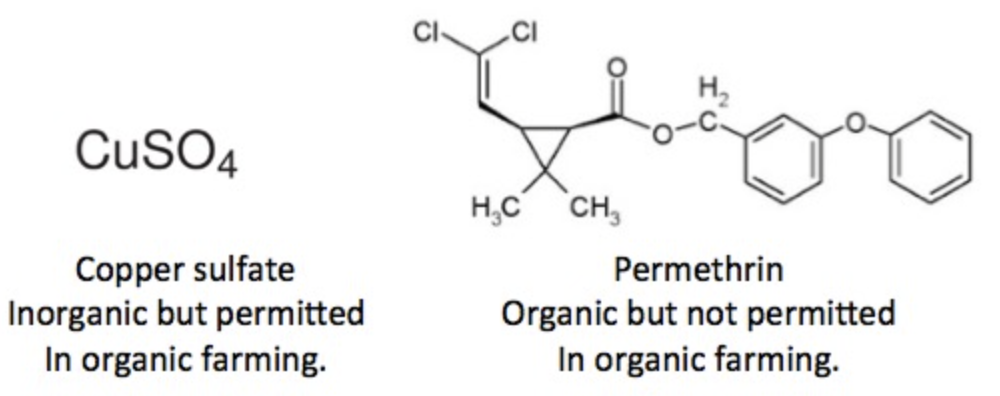

The list of permitted pesticides for organic farming can be found here. This raises an interesting paradox, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Wrap your head around this.

Copper sulfate is an inorganic chemical, but it is approved for use in organic agriculture. Conversely, permethrin is an organic chemical that is used in conventional agriculture but is not permitted in organic farming. This is the kind of thing that turns pre-meds into English majors.

Here are some other examples:

Boric acid, elemental sulfur, sodium hypochlorite (bleach), ammonium carbonate, and magnesium sulfate are all inorganic substances, but they are permissible in organic farming.

And...

High-fructose corn syrup, aspartame, red dye #40, glyphosate, BPA, neonicotinoid insecticides, and genetically modified foods are all organic chemicals (or contain them).

And just when you think the word couldn’t get more abused, along come the marketers.

THE MADNESS BEGINS

The following is just a sampling of some of the ways "organic" is misused. I kid you not.

.

Figure 4. 1) Now you can feel better about yourself when you're stuffing your face with Oreos. 2) Organic tampons? No comment. 3) Great news! Now you can smoke all day and be comforted by the fact that your cigarettes were made from tobacco that was grown without chemicals! 4) Glyde condoms are arguably the winner here. They are vegan – made from a material that doesn't involve harming animals. Better yet, the strawberry flavoring is organic! Seriously? If I want to enjoy some strawberry flavoring, there are far easier ways to taste it.

BOTTOM LINE

Chemistry's definition of organic is clear. The agricultural definition is OK (sort of), but it clashes with the chemical definition. But the marketing definition is a carnival free-for-all. That’s how copper sulfate gets the organic stamp of approval while permethrin doesn’t, and how we end up with organic Oreos, organic cigarettes, and organic tampons. If you really want something organic, don’t waste time squinting at labels. Just look in the mirror—you’re built out of organic molecules.

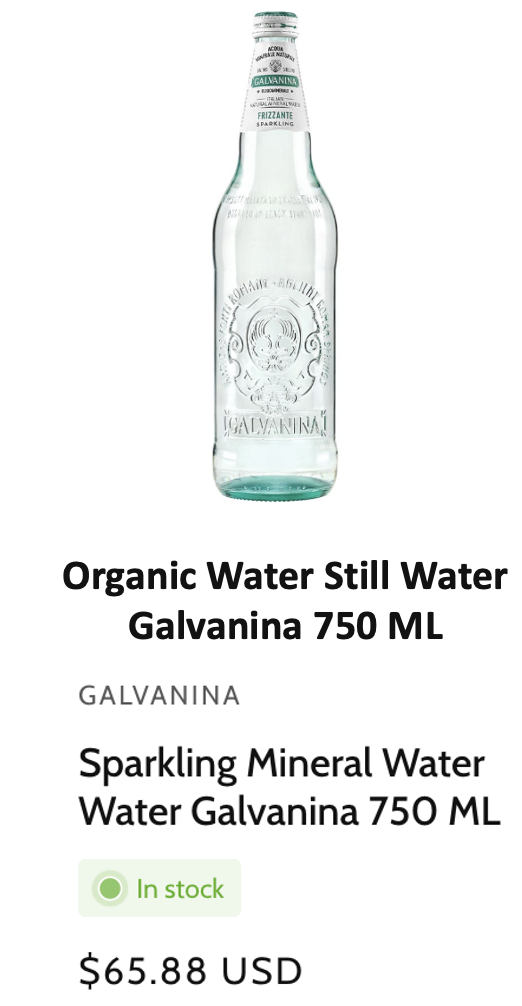

Apparently, so is this:

Organic water. Utter madness. And can anyone who buys it ($83/quart) be absolutely sure that it didn't come from a fire hydrant in Trenton?

I went into the wrong business.

NOTE:

[1] Urea, which was discovered in 1773 by a French chemist, was the first "organic" chemical ever isolated. It is considered to be organic even though the molecule does not contain a carbon-hydrogen bond.