“By September, we will know what has caused the autism epidemic, and we'll be able to eliminate those exposures." - Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Last April, RFK Jr. promised we would know the cause of autism within five months. It was an odd comment, since science hardly works on such a precise schedule, unless Mr. Kennedy already had a notion something was coming and was just waiting for an opportune time to disclose it. Indeed, it appears he had.

On September 22, 2025, five months and 11 days after the proclamation, “Mr. Kennedy and President Donald J. Trump … announced bold new actions to confront the nation’s autism spectrum disorder (ASD) epidemic”, blaming the increased incidence of autism on Tylenol (paracetamol, acetaminophen) consumption during pregnancy.”

The timing could not have been more convenient or auspicious -- at least from a litigation perspective. In December of 2023, a multidistrict action brought against acetaminophen manufacturers, Justice Denise Cote of New York’s Southern District rejected all five of the plaintiffs’ scientific experts’ testimony that prenatal exposure to acetaminophen caused autism (AD) and attention deficit disorder (ADHD), holding it scientifically unreliable and hence inadmissible under the Federal Rules of Evidence.

Months later, the plaintiffs proposed a sixth expert who opined that prenatal exposure to acetaminophen causes ADHD. That, too, was rejected by Judge Cote, and in August 2024, she dismissed the case. Unsurprisingly, the plaintiffs appealed to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Oral arguments were scheduled for October 6.

One week after the RFK announcement, the plaintiffs filed a letter with the Second Circuit, urging the court to consider the Department of Health and Human Services’ new position as a basis to overrule Judge Cote. The latest filing focuses on the work and testimony of Dr. Andrea Baccarelli, whose opinion, ostensibly relied on by the FDA, was eviscerated by Judge Cotes in the first 100 pages of her 148-page decision.

Oral arguments have been postponed to November, at which time the court will consider the extent of judicial gatekeeping of scientific evidence mandated under Daubert (and its progeny). Normally, appellate judges afford broad latitude to the ruling of trial judges on this issue, but there is a twist here; the plaintiffs are claiming failure to adhere to the (political) position of the administration would “pose grave separation of powers concerns.” Given that neither President Trump nor HHS Secretary Kennedy is eligible to testify as experts, it is hard to envision the Second Circuit embracing the plaintiffs’ argument, especially since the FDA itself expressly disclaimed any provable causal connection:

“It is important to note that while an association between acetaminophen and neurological conditions has been described in many studies, a causal relationship has not been established, and there are contrary studies in the scientific literature.”

The forthcoming Second Circuit decision, limiting or sanctioning judicial review of expert testimony, will be far-reaching, triggering the overall issue of allowing juries to decide scientific questions where the scientific community itself is in disagreement. Because plaintiffs have the burden of proving their claims, testimony that causation may be possible is not enough to sustain their case - the claim must be provably probable – by the preponderance of credible evidence. Even the FDA notes only “that while an association between acetaminophen and neurological conditions has been described in many studies, a causal relationship has not been established …”

Admissibility Standards under Daubert:

The Daubert standard proposes four non-exclusive, non-mandatory tests to assess the scientific reliability of proffered evidence, with the judge, as gatekeeper, assigned the responsibility of determining whether the evidence is sound enough to be evaluated by a jury. The enumerated tests are:

- Whether the theory or technique employed by the expert is generally accepted in the scientific community

- Whether it's been subjected to peer review and publication

- Whether it can be and has been tested

- Whether the known or potential rate of error is acceptable

If the scientists can’t agree, how can we let a jury decide?

The evidence championed by the plaintiffs and supported by a small ad hoc group of physicians describing themselves as a consensus group is riddled with methodological errors. Furthermore, it is controverted by official consensus groups, which assert the lack of a proven causal connection —a key consideration under Daubert.

- The US-based Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) found that “the weight of the evidence is inconclusive.

- The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists noted that “[c]urrent advice is that [acetaminophen] remains safe for use during pregnancy and breastfeeding.”

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) noted that studies “show no clear evidence that proves a direct relationship between the prudent use of acetaminophen during any trimester and fetal developmental issues.”

- A “Consensus Counterstatement” by 60 scientists and clinicians, affiliated with the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, criticized claims of causal connection, noting studies depicting a connection were “limited by serious methodological problems, … that interpret the data challenging,” prompting even those arguing a connection to admit: that “we avoided any inference of causality in our Consensus Statement.”

Dr. Bacarelli’s testimony, according to Judge Cote, is riddled with flaws, rendering it inadmissible. For one thing, to bolster his position, he utilizes novel approaches not generally accepted in the scientific community, including a transdisciplinary analysis, i.e., selectively and subjectively combining data relating to two hand-picked conditions, Autism and Attention Deficit Disorders, without including other diseases in the same neurological category. His subjective (and hence unreliable) approach is evident in the research he selectively relies on, cherry-picking results that favor his position and discounting those that contradict him, a hallmark of junk science in toxic tort cases used by plaintiffs to support scientifically unreliable opinions.

"The extent to which the technique relies on the subjective interpretation of the expert" influences its admissibility. “The test must rule out `subjective belief or unsupported speculation.”

Bacarelli’s approach also contravenes basic epidemiologic methodology, further compromising its validity. When confounding issues enter an analysis, the recommended approach is not to bundle more studies or data categories together as he does, but to stratify results by category. And while Bacarrelli’s research has been peer reviewed and published, at least his 2025 study was surely litigation-driven, further diminishing its courtroom value:

“Testimony proffered by an expert is based directly on legitimate, preexisting research unrelated to the litigation, provides the most persuasive basis."

Additionally, the 2025 study, which finds association but not causation, limits legitimate conclusions that might be drawn regarding causality:

“Population-level time trends, which may be influenced by improved diagnostic tools and awareness, cannot establish causation for any single exposure, such as acetaminophen, and may raise the risk of ecological fallacy.”

More Of Bacarelli’s Errors

“.... It is really challenging to separate out the effect of Tylenol from the effect of infections that may lead people to take Tylenol. - David Mandell, U. of P. School of Medicine.

Further rendering the studies suspect is the effect of confounding factors. Healthy people, especially if pregnant, do not take drugs, including acetaminophen. That the underlying illnesses triggering consumption may have been responsible for any apparent connection between drug and disease is a classic example of confounding, which must be addressed, else the study loses its evidentiary value.

Without accounting, controlling, or ruling out confounding factors, Judge Cote found the possibility of error too high to render plaintiffs’ proofs reliable. Other confounding factors, such as genetics, which, according to Judge Cote, account for a heritability of 80% of cases, may be the true culprit. Indeed, studies demonstrating a positive association between drug consumption and ASD disappear when genetics are accounted for. [1]

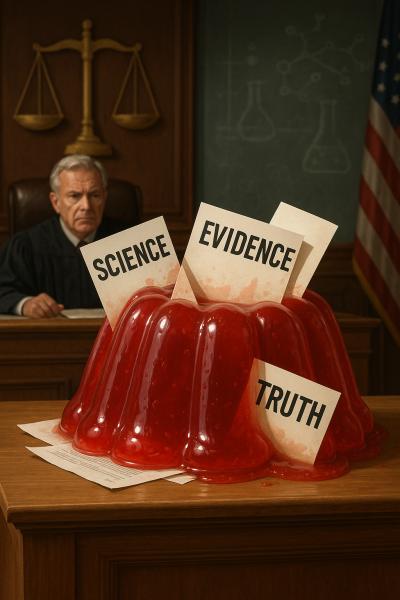

The Jello-theory of disease

The myriad potential causes targeted for lawsuits or attack, independent of Tylenol, reflect an oft-cited maxim of defense lawyers. If you sling around a multitude of possible causes, just like jello, something might stick:

FDA Commissioner Dr. Marty Makary doesn’t think genetics are responsible, nor does he blame Tylenol. He believes an underlying autoimmune disease causes autism. Other possible risk factors, including premature birth or low birth weight, maternal health problems, and parents conceiving at older ages, are also ignored by Bacarelli.

Uncited in Judge Cote’s opinion are additional potential causal (and confounding) factors, further increasing the likelihood of erroneous conclusions. Recall that Secretary Kennedy contends that vaccines cause autism, and the MAHA report claims that ultra-processed foods, food dyes, and additives may be responsible. Mr. Kennedy has also championed the connection between autism and environmental exposures, including air pollution, drinking water contaminants, heavy metals and solvents, pesticides, and diesel exhaust, which reportedly causes “autism-like behavioral changes” in mice. The plaintiffs’ bar isn’t satisfied. First, they tried to tie prenatal consumption of the antidepressant Lexapro to autism. When that failed, they went after Tylenol. Now that that case is on the rocks, they need another target.

“There may be another path to compensation. … [which] are gaining new currency after the Tylenol cases faltered in the MDL…We encourage parents interested in bringing a Tylenol lawsuit to consider filing a toxic baby food lawsuit.” – Plaintiffs’ Lawsuit Information Center

In August, RFK admitted that his initial timeline was somewhat optimistic, and “promised unqualified answers within another six months.” Who knows? We may have another potential defendant in six months.

In the weeks ahead, the Second Circuit will decide whether science in the courtroom remains a disciplined inquiry or dissolves into gelatinous conjecture. If the judges uphold Daubert’s demand for reproducible evidence, the Tylenol-autism claims will firm up—or collapse—on their merits, not on politics, passion, or presidential press releases. But suppose the court relaxes its gatekeeping in deference to shifting administrative winds. In that case, it risks turning every complex disease into a legal food fight where any colorful theory can be hurled until it sticks. For families seeking answers, for companies making essential medicines, and for a public that must trust both doctors and courts, the choice between rigor and rhetoric could not be clearer—or more consequential.

[1] Recent research finds autism may be a genetic price humans paid in our evolutionary journey.