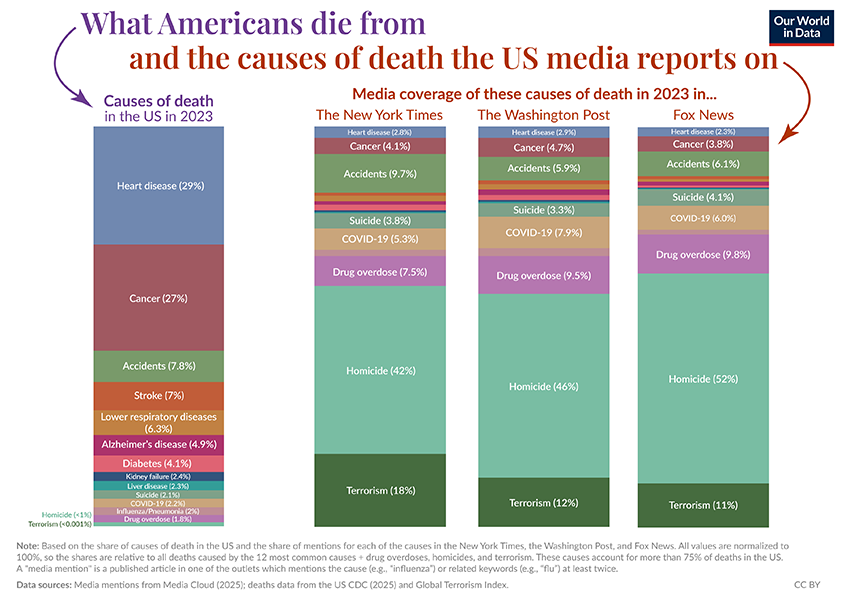

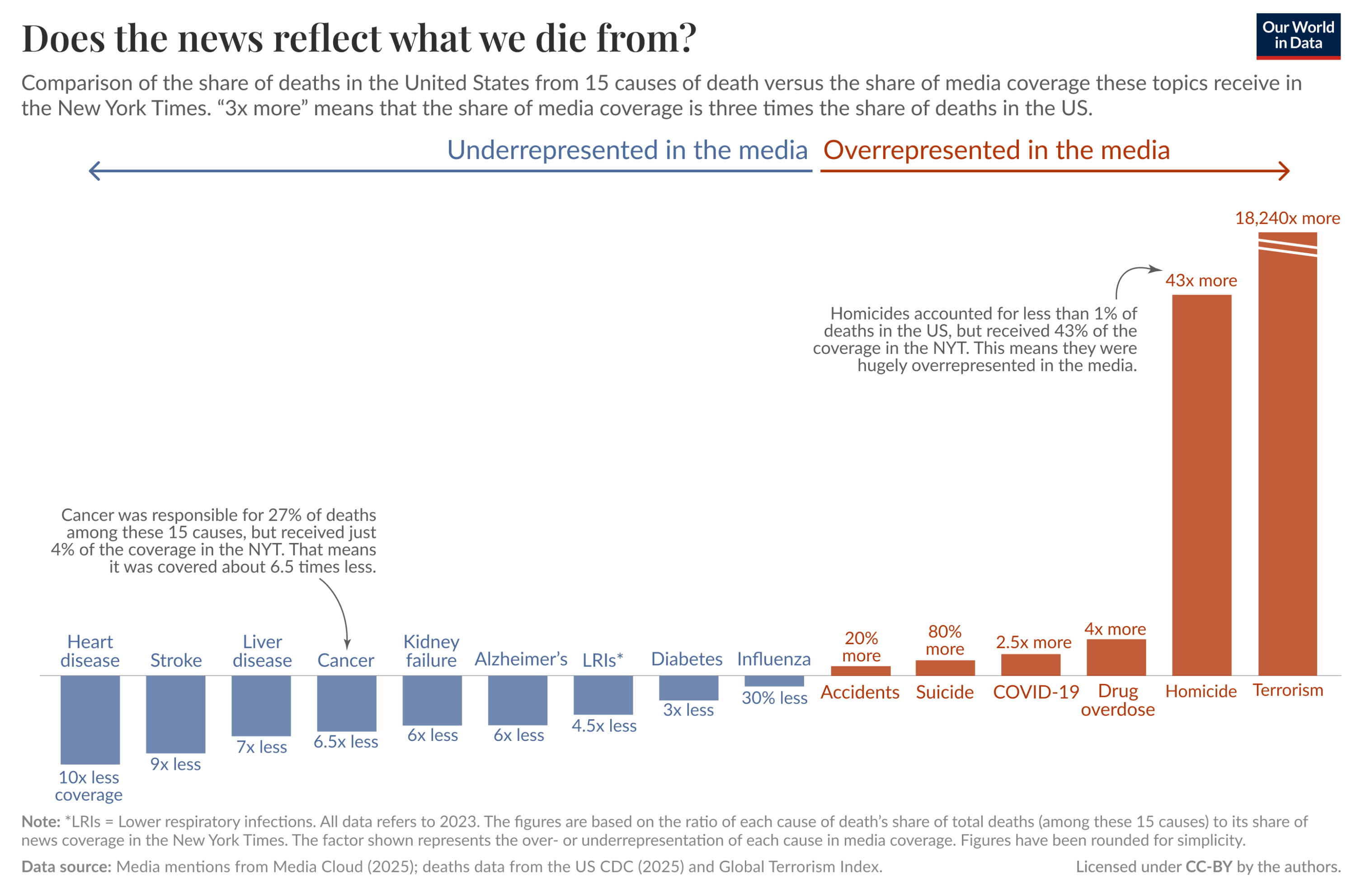

The folks at the World in Data recently did a study of deaths in the US, comparing the reported number of deaths by the CDC to the reports in three legacy medias, hopefully across the political spectrum; the NY Times, the Washington Post, and Fox News.

You can plainly see a disconnect, heart disease, our biggest killer gets nearly a thousand-fold less coverage than our smallest cause of death, terrorism. The distortion transcends political or ideological leanings, prioritizing drama and immediacy over statistical reality.

The Emotional Reality of News

As the researchers note, dying of heart disease is not news. Its brief mention serves the journalistic goal of “We report…” But in our modern media environment, the old adage “if it bleeds, it leads” has evolved into something more pervasive. The continuous 24-7-365 news cycle, with its repetition and urgency, makes it increasingly difficult for “…you decide” to represent reality accurately. What we consume is not a mirror of the world as it is, but of how the world makes us feel.

This bias is both structural and psychological. Psychologically, audiences are drawn to narratives filled with conflict, danger, and personal drama. Structurally, journalists and editors—driven by the economics of clicks, subscriptions, and advertising—gravitate toward stories that command attention. Emotional responses are stronger drivers of engagement than facts, and fear and outrage are especially magnetic. Our media thus orbits around emotional gravity, not statistical weight.

Repetition Shapes Belief

As the Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels chillingly observed, “If you tell a lie big enough and keep repeating it, people will eventually come to believe it.” His words were intended to justify deliberate deceit, but they also illuminate a subtler dynamic in today’s information ecosystem. Modern news outlets, though not spreading lies, achieve a similar psychological effect through repetition and emphasis. By continually spotlighting rare but dramatic events—murders, terrorist attacks, disasters—the media amplifies their emotional frequency and importance. Repetition transforms rarity into familiarity: what is exceptional feels common, and what is common fades from awareness. In this way, the cycle of selective coverage distorts public perception, shaping fear and policy around the extraordinary rather than the everyday.

The Machinery of Continuous Emotion

In earlier decades, technological limits provided a buffer: newspapers arrived once or twice a day, and television news had its appointed hour. Today, the news never sleeps. Stories reach audiences in real time, framed with striking visuals, emotional language, and viral momentum. Catastrophe anywhere on the globe becomes immediate and intimate, leaving us in a state of permanent emotional crisis. All of our media now cries wolf, all day long.

Social media intensifies this dynamic by personalizing the bias—curating feeds that reward outrage, fear, and affirmation. The public and the media feed one another in a feedback loop of attention: audiences click on what provokes emotion, and media outlets produce more of it to survive in the attention economy.

The data expose a sobering truth: the media landscape no longer reflects the statistical reality of the world but the emotional reality of what captures attention. Headlines reflect not the greatest dangers to our lives, but the strongest reactions of our hearts When the media amplifies the rare and sensational, it warps our collective sense of risk, steering fear and policy toward the exceptional instead of the everyday. Reclaiming a sense of proportion requires conscious awareness—a willingness to seek out data alongside drama, to measure what matters rather than what merely moves us. In an age of endless headlines, the most radical act of discernment may be learning to separate statistical truth from emotional noise.

Source: Does the news reflect what we die from? Our World in Data