As a physician, I am attuned to the tension between my craft, grounded in “gold standard” science, and its artful application, grounded in the values of my patients as I experience them. End-of-life issues are complex because empirical questions (what happens, works, or harms) that can be approached by science are deeply entangled with value questions (what should count as a good death, autonomy, dignity, moral limits). The recent decision by Governor Hochul of New York to advance and promise to sign a Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) bill provides us with the opportunity to consider that entanglement.

The Medical Aid in Dying bill includes multiple safeguards intended to protect patient autonomy and reduce the risk of abuse. Among them is a familiar requirement: two or more physicians must agree that a patient has a terminal illness that is incurable and irreversible and is expected, within reasonable medical judgment, to result in death within six months. It is this final condition that deserves closer scrutiny.

Rather than focus on the value questions raised by MAID, which will always be subjective, let’s focus on the determination of “six months,” an empirical clinical concern, one where science-based evidence should be strong. If the six-month window is meant to anchor ethical decisions in clinical objectivity, it matters how reliable such predictions actually are.

Forecasting Death: An Uncertain Science

One early study used statistical modeling to estimate six-month mortality among community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 and older who reported their health was “much worse” than one year prior. The model incorporated comorbidities, activities of daily living, social functioning, fatigue, and overall health perceptions—factors commonly relied upon in real-world prognostication.

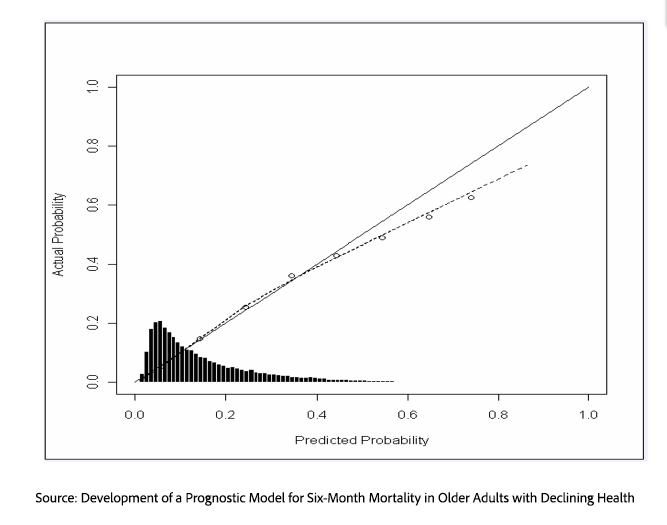

This figure shows the predicted actual number of deaths within the cohort and the six-month window. Perfect prediction would follow that 45° “perfect calibration” line. The results revealed a consistent pattern: clinicians were reasonably accurate at predicting death over very short time horizons—days to weeks—, but accuracy declined sharply when predictions extended to 6 months. As confidence in an impending six-month death increased, physicians systematically overestimated how many patients would actually die within that window.

This figure shows the predicted actual number of deaths within the cohort and the six-month window. Perfect prediction would follow that 45° “perfect calibration” line. The results revealed a consistent pattern: clinicians were reasonably accurate at predicting death over very short time horizons—days to weeks—, but accuracy declined sharply when predictions extended to 6 months. As confidence in an impending six-month death increased, physicians systematically overestimated how many patients would actually die within that window.

Meta-analyses focused solely on cancer patients show a similar pattern of limited six-month prognostic accuracy. Predictions improve over shorter time horizons, primarily because individual disease trajectories vary so widely that objective measures lose discriminatory power. As a result, most prognostic models rely heavily on functional status, an inherently interpretive measure, prompting researchers to conclude that such tools function better as “conversational aids” than as precise predictors.

Across MAID studies, roughly two-thirds of recipients have cancer, followed by smaller but comparable proportions with neurologic, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), however, shows the strongest association with MAID use. Notably, researchers concluded that MAID uptake was driven more by illness-related factors than by eligibility rules, cultural context, or access to palliative care—underscoring how disease trajectory, rather than policy precision, shapes decisions. This becomes especially salient when decline unfolds unevenly over years rather than months.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) and related disorders (PDRD) are the second most common neurodegenerative illnesses, ultimately leading to increasing disability, complex motor and non-motor symptoms, and shortened survival. A study of prognostic factors in referral to hospice care using the same six-month window found that advancing complications resulting in functional decline, e.g., swallowing problems resulting in aspiration, falls and fractures, and cognitive changes, were the prime drivers. However, their onset was across years, and it was only their additive confluence that prompted initiation of hospice care. Patients were often referred late (or not at all) for hospice and palliative care despite high symptom burden.

In short, across a broad spectrum of illnesses, the conditions that prompt consideration of MAID are often easy to recognize once they are present, relying on clinical observation and judgment. Predicting those same conditions six months in advance, however, is far more difficult, particularly for neurologic diseases with variable and prolonged trajectories.

Scientism Shifting Blame? When Prognosis Becomes Moral Cover

Scientism is the belief that the methods and authority of, in this instance, physicians are highly reliable and the legitimate means of answering important questions. Among its common features are

- Overconfidence in quantification and prediction, even when the domain is complex and uncertain

- Treating what is measurable as if it is what is most important

- Using scientific language to make value judgments sound objective

- Reframing normative questions (“should we…?”) into technical questions (“can we…?”)

The legislation reframes the ethical agony of “should we” as “how we.” The studies of end-of-life predictions, limited as they are, show that the three other features of scientism are alive and well in New York’s and other states' MAID directives. While scientism often discounts the “live experience,” in this instance of patients and caregivers, the legislation elevates that concern. However, cloaking requirements in medical prophecy is an overreach: treating scientific measurement and prediction as if they can replace moral reasoning, values, and human meaning.

Science Describes, Ethics Prescribe

Research can help determine whether safeguards reduce measurable harms and clarify likely outcomes. But legislation, however well-intentioned, cannot fully reconcile patient autonomy with the obligation to protect vulnerable people. Critics of MAID rightly note that social pressures can operate as a form of coercion even without a single coercer, and that normalizing MAID may subtly reshape expectations of the sick, disabled, or elderly. A six-month prognostic threshold cannot resolve these concerns by invoking science alone.

Good end-of-life care recognizes that narrative, meaning, relationships, spiritual beliefs, dignity, and moral limits are not secondary considerations but decisive dimensions of care. These judgments emerge through shared deliberation between physician and patient. They cannot be validated solely by clinical trials, and, like all human judgments, they will sometimes be flawed. Irrespective of how we personally resolve the ethical prescription, science can describe patterns, but it cannot decide whether they should “count,” or what moral limits should govern our responses.

The six-month prognostic window is not a neutral scientific gate; it is a moral boundary disguised as clinical precision, one that risks laundering uncertainty into legitimacy. In practice, the very tools meant to make eligibility “objective” lean heavily on functional decline and clinician judgment, precisely where subjectivity and bias are most complex to avoid and where social vulnerability can be most consequential. A humane society can debate whether MAiD belongs within the repertoire of care, but it should not pretend that a physician’s estimate can settle the ethical burden. The more honest path is to treat prognostication as fallible, safeguards as necessary but insufficient, and end-of-life decisions as irreducibly human.