How many nursing home patients have died in nursing homes?

To clarify, we are talking about the deaths of residents while they remain in nursing homes -like the statistics on the deaths on the Diamond Princess set at roughly 1.1%.

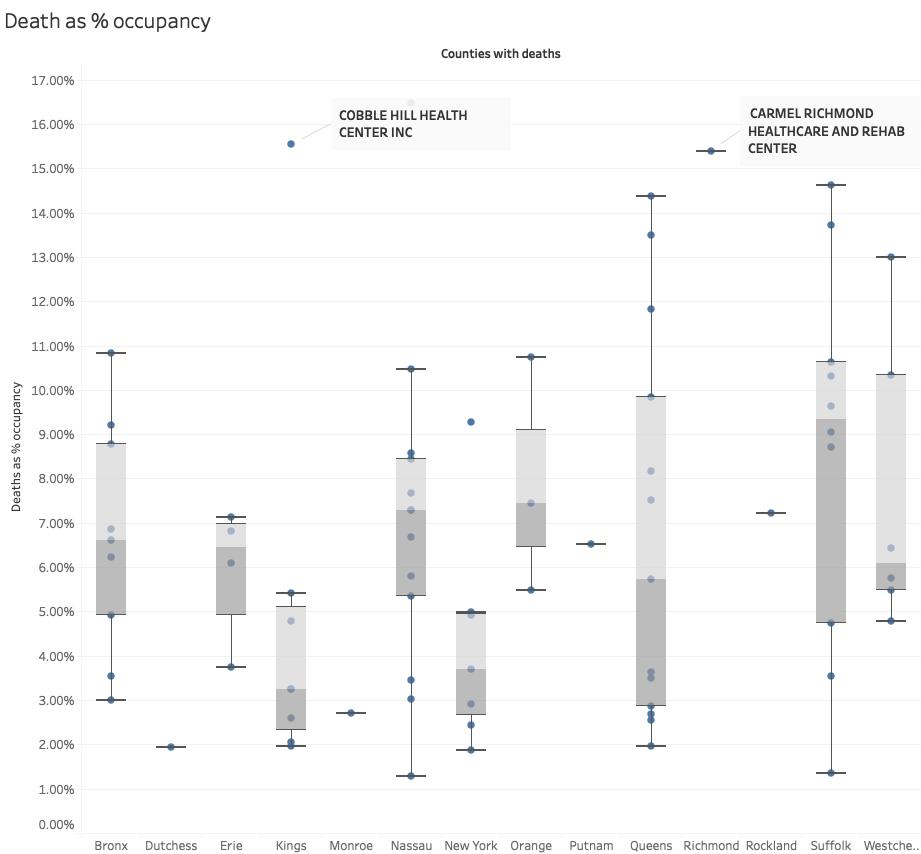

Cobble Hill, with a mortality rate of 15.4% of its average occupancy, has gathered the headlines. Still, as the figure shows, the second outlier, Carmel Richmond Healthcare, in Staten Island has all but been ignored. More importantly, you can see wide ranges in mortality within each of the reporting counties. [1]

Across all of the nursing homes with fatalities, the mortality rate is 6.47%, and when the denominator is changed to all of the nursing homes in the state, the average is 1.7%. The dramatic decrease is because there are so few reported deaths state-wide. 12% of nursing homes account for all the reported deaths.

What makes these nursing homes different?

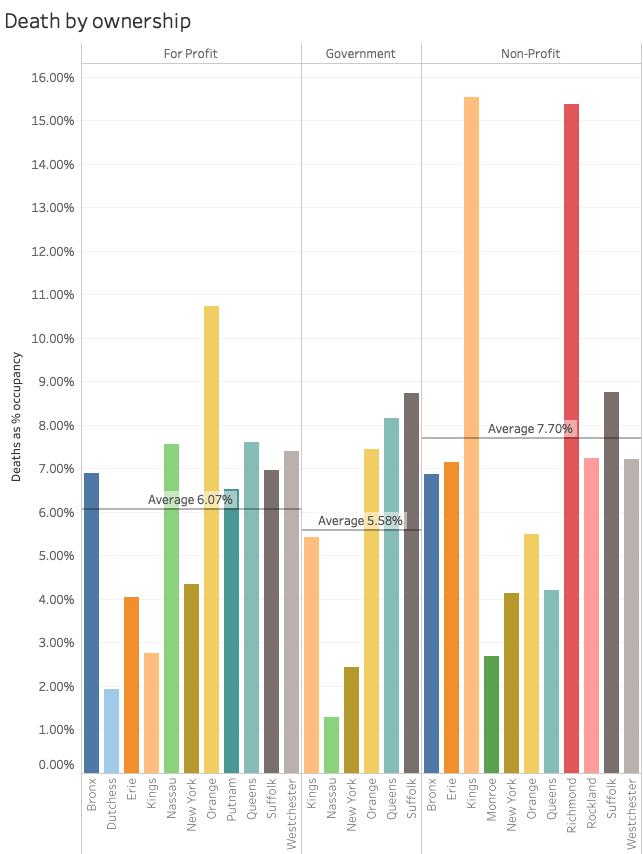

Of course, the first thought might be ownership, do for-profit nursing homes do a better or worse job of protecting their patients. As the bars show, there is a wide range of mortalities associated with ownership resulting in very close percentages when aggregated. While government-run facilities had the lowest and non-profits the highest mortality rates overall, the difference was a little over 2%. (The two outliers were both non-profit nursing facilities which may account for the disparity) No smoking gun to be found here.

Of course, the first thought might be ownership, do for-profit nursing homes do a better or worse job of protecting their patients. As the bars show, there is a wide range of mortalities associated with ownership resulting in very close percentages when aggregated. While government-run facilities had the lowest and non-profits the highest mortality rates overall, the difference was a little over 2%. (The two outliers were both non-profit nursing facilities which may account for the disparity) No smoking gun to be found here.

CMS Nursing Home Compare

CMS gathers reports every three years on a range of measures and scores from every nursing home in the country; all contribute to their "Star" ratings. 77% of the current data was collected in 2019 or 2020. There is no significant difference in the mortality rate between these facilities based upon how many hours spent daily with patients or staffing levels. The only primary measure where there was a significant effect was in the average daily occupancy, where more occupants lead to lower mortality. Whether this is due to the mortality rate being diluted by more patients or by some standardization of care by the facility is unclear.

CMS characterizes deficiencies in measures of health, based on their standard surveys, as well as reviews prompted by complaints. Those deficiencies include those due to administration, environment, abuse or neglect, nurse and physician services, nutrition, pharmacy, quality of life, resident care plans and assessments, as well as patient rights. There was no correlation for any of these with mortality rates, in the standard or complaint prompted surveys.

Emergency room visits or re-hospitalization while in a nursing home are considered inadequacies of care. CMS calculates a score based on those events, further categorizing them for short-term residents using the nursing home as a bridge back to their homes, and long-term residents. There can be several reasons for a return to the ED or hospital including the poor selection of a discharge location by the hospital – the patient is too sick to be there; inadequate monitoring of patients by the nursing home and attending physician necessitating emergent care or re-hospitalization, or an unexpected decline in a patient's health.

For the short-term metrics, only a handful of nursing homes were worse than expected [2], sending more patients to the ED and hospital than anticipated. As a generalization, as the nursing homes' performance became worse than expected, their mortality rates rose. To me, this suggests inadequate monitoring and care – the idea that the nursing home staffs were unprepared for this problem. But this opinion is tempered by the fact that we do not know how many deaths were among recent admissions.

For the long-term metrics, nearly all the nursing homes performed better than expected, that is, they held onto their patients taking care of them "in house" rather than referring them to the ED or hospital. That handful of nursing homes that sent more patients to the ED or hospital, in general, had lower mortality rates – perhaps reflecting a shift in the location of the death to the hospital and their mortality statistics.

Blame or Shame?

The States are beginning investigations into nursing home deaths, looking for where to place blame. There is no smoking gun to be found, raising the question of whether the "Star Ratings" criteria are helpful at all. I am inclined to believe that the disregard we show to our elderly frail, in terms of the resources we provide both human and material, is not unlike the disregard we hold other disadvantaged – out of sight, out of mind. The pandemic just brought the disparity into the open, one can only hope that we will change our approach in the post-COVID-19 world.

[1] For those not familiar with a whisker-box plot, the whiskers show the outliers, both low and high, the box contains 50% of the data points with the line within the box indicating the average.

[2] CMS calculates an expected rate of ED visits, and readmissions based on case-mix, the severity of illness among a nursing home's patients.

Data Sources: New York State Department of Health

CMS Nursing Homes Compare Dataset

Dataset available on request.