There was never really much doubt that a class of drugs (1) intended to treat depression and anxiety would fail to act as analgesics (painkillers). After all, it's been more than 120 years since the discovery of aspirin and heroin, and we are still stuck with versions of the same two classes of analgesic drugs – NSAIDs and opioids to treat pain. This hasn't stopped the search for an acceptable alternative to these two classes; both have upsides and downsides. But it's fair to say that this search has been a dismal failure – something that tens of millions of people with under or untreated pain will tell you.

Last week, journalist Pat Anson, the editor of the Pain News Network site, reported on the conclusion of a new, long, and complex review in BMJ – that antidepressants are ineffective for most chronic pain. The underlying data was based on 26 meta-analyses of trials that together involved more than 25,000 participants. In other words, a whole lot of data points.

It was rough going; nonetheless, with more than a little help from Dr. Stan Young, an expert biostatistician and ACSH advisor, I focused on the most important data table the one from which the conclusions were drawn. Perhaps, with a little luck, I’ll be able to explain what’s going on.

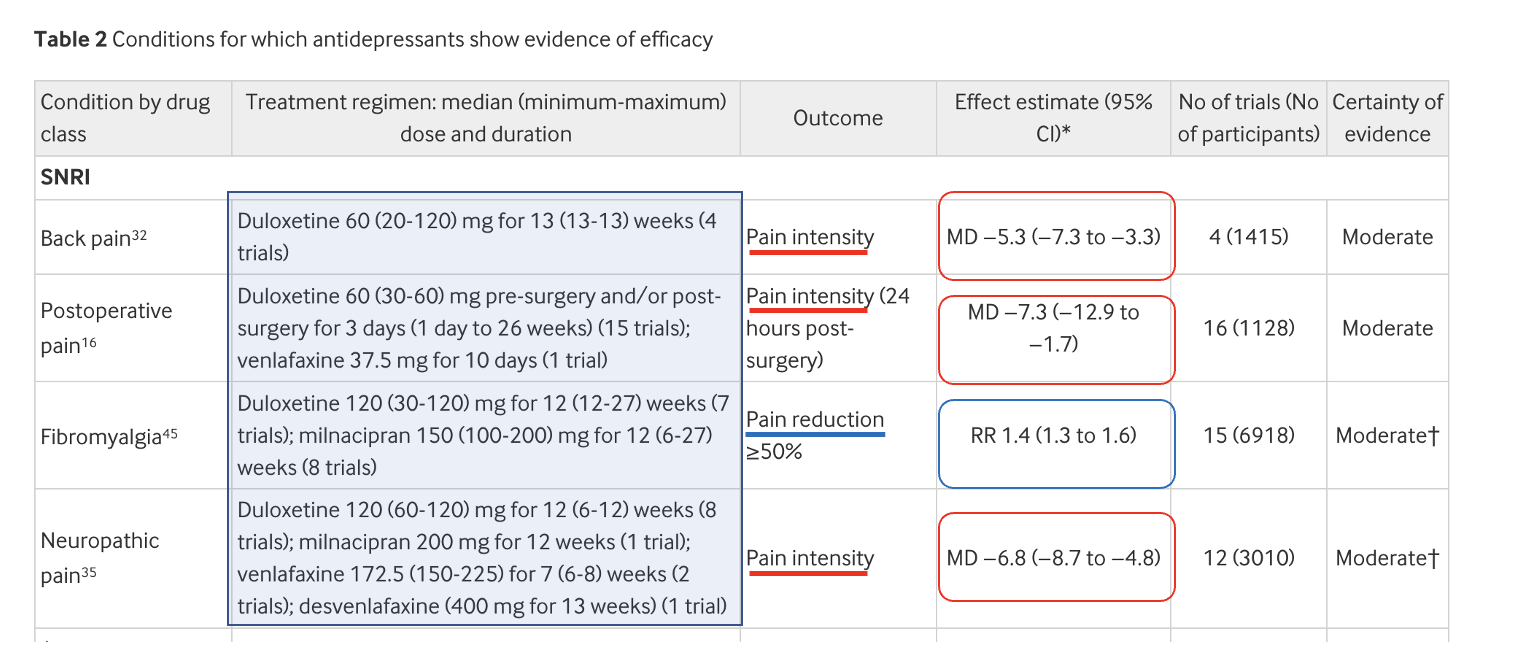

Table 2 - The heart of the study

Let's go straight to Table 2. It contains the data from meta-analyses of 11 painful conditions where there was some level of evidence that antidepressants were effective analgesics; these results formed the basis for the conclusion. But seven of the 11 meta-analyses were judged as having "low certainty of evidence." These will be ignored. The remaining four studies were characterized as having "moderate certainty of evidence."

Below are the data from the four acceptable studies (based on a total of 47 trials) with analysis and comments from Dr. Young and me.

ISSUES WITH TABLE 2

- Different doses, different drugs, and other confounders (light blue shaded box)

It becomes immediately apparent that in the 47 trials in this section of Table 2, there are confounders in all four groups of conditions. These include:

- A rather wide range of doses of the drug (back pain)

- Different drugs, different doses, and a huge endpoint time ranging from one day to 26 weeks (post-op pain)

- Different drugs at different doses, different doses, and a significant range of the endpoint time (fibromyalgia)

- Four different drugs, moderately different doses, and similar time endpoints (neuropathic pain)

With this many variables, some of them with an extensive range within the same study, it is difficult to be confident in exactly what is being measured in these four trials. Here's why.

- Negligible "positive" effects

Studies 1,2, and 4, in the red boxes, show a mean reduction in pain scores. But these numbers, which range from a decrease of 5.3 to 7.3, are based on a 100-point pain score. Is this very small difference real or meaningful? Yes and no.

Dr. Young: "Studies 1, 2, and 4 have large sample sizes, and the reported effects are too large to be attributed to chance."

In other words, the statistics are reliable and the difference in pain scores was real but very small. But does this mean that antidepressants are actually effective in treating pain?

Dr. Young: "Although the data are sound, the effects are very small, in fact, too small to be clinically useful to any individual."

This statement reflects the opinion of the study authors, although they do not state it quite as definitely:

We purposefully chose not to make judgments about the clinical importance of observed effects for each condition because commonly used thresholds, such as the 10 point reduction on a 0-100 scale commonly used in musculoskeletal pain research, are arbitrary, context specific (specific condition, treatment, comparison, and outcome), and potentially misleading if interpreted inappropriately. Given the challenges of making judgment calls about the clinical relevance of treatment effects, we encourage clinicians first to conduct a holistic assessment of the evidence, which includes an appraisal of the effect size, certainty of available evidence, and trade-offs between benefits and harms of each antidepressant, and then to involve patients in these discussions.

Ferreira, et. al., BMJ 2023;380:e072415, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-072415

- A low relative ratio (RR) means what we're seeing is probably not real

The evaluation of pain control for fibromyalgia (study 3 in the blue box) is not expressed as a reduction in the pain score. Instead, the endpoint was the RR (relative risk, chance) of the drugs attaining an endpoint of a >50% reduction in pain. For the 15 trials taken together, the RR is 1.4. In other words, People who took antidepressants were 40% (1.4X) more likely to reach the endpoint. Is this meaningful? Dr. Young says no. The problem is this number is too low to be of value.

In meta-analyses, generally a RR of 2 or 3 is weak, either in evidence, reliability or both.

ACSH advisor Dr. Stan Young, Private communication, 2/3/23

In meta-analyses with so many variables, a 1.4-fold effect is probably not real; it is more likely due to confounders in the data.

The Bottom Line

Although this is not explicitly stated, it is (in my opinion) indisputable that antidepressants do not offer a legitimate benefit for chronic pain.

None of this is surprising. The "anti-opioid frenzy" era persists, and academics can't go wrong by studying any opioid alternative, no matter how bad. Now you can add antidepressants to the growing list of faux painkillers, which includes gabapentin/Neurontin and Tylenol, both of which I've already eviscerated.

They may not work but at least they're not opioids, right?

NOTES:

(1) It would be more accurate to say two classes; the SSRI/SNRI class (newer drugs e.g. Lexapro, Cymbalta, Effexor...) and the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), e.g. Elavil (amitriptyline) and Asendin (amoxapine). The two classes differ chemically but work in more or less the same way. The study showed no effect of the TCAs for several conditions and no conclusive evidence for all the others.