The pharmacokinetics of ethanol and THC differ quite a bit. From a metabolic point of view, despite how some feel the “morning after,” ethanol has a short half-life of 1 to 2 hours. THC, whether smoked or swallowed, hangs around far longer, one to two days. While both ethanol and THC undergo metabolism in the liver, ethanol is primarily metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase, forming water and CO2. By contrast, THC undergoes hepatic metabolism to form various metabolites, including the psychoactive 11-hydroxy-THC. Furthermore, THC, being a lipophilic (fat-loving) chemical, is stored in body fat, where it is slowly released.

Two problems arise:

- We can equate a given blood level of alcohol with impairment, but that is not the case for THC because of its metabolite, 11-hydroxy-THC, which is also psychoactive. To equate impairment with THC, we would have to include both. Unlike alcohol, there is no science-based concentration of THC that is recognized as being correlated with impairment,

- THC can be present for longer periods, so it becomes more challenging to draw a temporal causality between its absorption by toking up or chowing down and an event of concern – an accident.

A new study in Clinical Toxicology offers a solution.

I will leave the heavy lifting of a chemical explanation to my colleague Dr. Bloom, but the essence of their new test measures the ratio of THC to a non-psychoactive metabolite, 11-nor9-carboxy-THC. [1]

The researchers identified a group of healthy adults, between 25 and 40, to come in with some Colorado weed and smoke or vape for 15 minutes and have blood levels taken before and 15 minutes afterward. The concentration of THC in the product was given on the label. The researchers recruited both occasional users (1-2 days/week for the last month) and daily users.

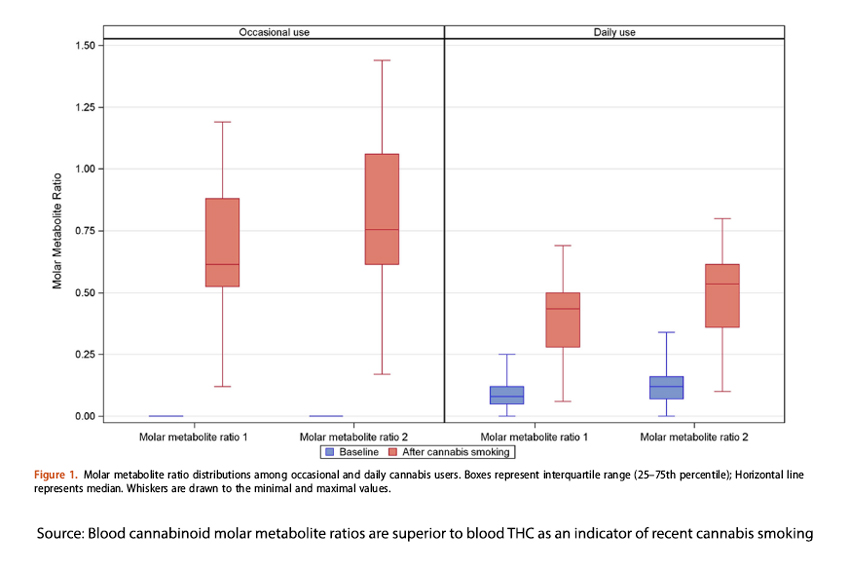

The newly designed test determined the ratios of THC and one of its metabolites. The first, "Molar 1," measured the ratio of THC to 11-nor9-carboxy-THC, the non-psychoactive metabolite. The second, "Molar 2," measured the ratio of THC plus its psychoactive metabolite (11-hydroxy-THC) to 11-nor9-carboxy-THC.

In general, the participants were evenly divided by gender and age. Daily users “used” more frequently, 5.1 times a day (vs. 1.4 times a day for occasional users when they smoked). Daily users consumed more in terms of weight, 334mg for everyday users vs 113mg for the occasional, and their pot was slightly more potent. Chronic users smoked longer, 11.5 vs. 5 minutes, and took more hits, 17 vs. 8.

As would be expected, the daily users already had a THC level in their blood before lighting up – remember, THC has a long half-life. All the huffing and puffing by the chronic users resulted in a four-fold higher level of THC than in the occasional user, even though the self-reported levels of being “high” were greater in the occasional users, suggesting that chronic use impairs the perception of being high, reminiscent of the concerned over buzzed drinkers.

The box and whisker plot shows that both of the two molar metabolite ratios readily identified the recent use of THC in both chronic and occasional users. As the researchers note

“…in a forensic determination, it may be advisable to favour the value with the higher specificity, and hence lower false positive rate.”

In establishing a cut-off value, there was a slight difference in the results for chronic users vs. occasional users, but overall, the specificity was 97%. The bottom line of the study is that these metabolite ratios are far more accurate in identifying the acute use of THC. It does not establish ratios associated with various levels of objective impairment, the second critical component in law enforcement testing and evaluation for impairment. However, given a ratio that appears to be time-responsive, further studies can elucidate those parameters. There will also have to be a consideration of whether the metabolic time frame is unchanged, slowed, or enhanced by chronic vs. occasional use.

With the growing use of recreational marijuana, we will, unfortunately, need a reliable test of impairment to have a better grasp of how marijuana use might be a component in accidents, both on the road and in the workplace. This is a big step in that direction.

[1] For those with a more chemical bent, they are looking at the molar ratios. I will leave that to Dr. Bloom to discuss.

Source: Blood cannabinoid molar metabolite ratios are superior to blood THC as an indicator of recent cannabis smoking Clinical Toxicology DOI:10.1080/15563650.2023.2214697