A recent study in Addiction reported that “ultra-processed food addiction” (UPFA) affects roughly one in eight adults over 50—and nearly one in five women aged 50–64. These are striking numbers, making the study’s abstract enticing. However, they are only as strong as the chain of assumptions that underlie them. Let’s break down the study in an organized, skeptical step-by-step way to see whether we agree with the researcher’s conclusions.

- What question are the authors really asking?Are they trying to establish causation, describe a trend, or argue for a new diagnosis?

- How are the relevant variables defined? Are the study’s definitions (here, ultra-processed foods and food addiction) widely accepted, or are they still contested?

- Which instruments and measures were used, and are they fit for purpose?

- How do the authors link results to broader narratives? Does the narrative clarify mechanisms, or import emotional, value-laden rhetoric that could shape our interpretation?

By examining definitions, metrics, and context, we can determine the weight that those headline numbers deserve.

The Researchers Set the Stage

As with most studies, it begins with an introduction providing context for the research and the researchers’ underlying reasoning. The study begins by noting a long-term shift in the American diet: over the past half-century, ultra-processed foods (UPFs)—industrial formulations high in refined carbohydrates, added fats, and engineered flavorings—have become the dominant source of calories. By the late 1970s and ’80s, tobacco companies had entered the food industry, using their marketing expertise to promote these products. Today’s adults in their 50s to 70s grew up during that transformation. The researchers suggest this cohort was especially vulnerable to addiction “owing to heightened reward sensitivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation.”

Invoking the “tobacco playbook” lends rhetorical weight to the argument, since nicotine addiction is well established. Yet critics might see this analogy as evidence of bias, with researchers beginning with a conviction about UPFs’ addictiveness. The key question, then, is whether the study tests that idea objectively or selectively supports it. With that framing in mind, the next step is to examine how the study measured “addiction.”

Measuring Addiction: Tools, Tests, and Assumptions

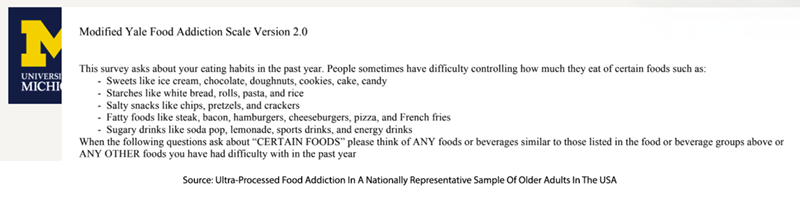

To assess whether early exposure to UPFs had lasting effects, the researchers analyzed survey data from 2,038 U.S. adults aged 50 to 80, who were representative across various demographic categories, including race, income, and education. They used the modified Yale Food Addiction Scale (mYFAS), which adapts diagnostic criteria for substance-use disorders, such as loss of control, craving, and tolerance to eating behaviors.

One of the key points in debating the value of a scientific study is the tools used for measurement. Researchers applied the mYFAS to gauge “ultra-processed food addiction,” relating it to weight, self-rated health, and social isolation. For the skeptical, this is a treasure trove of concerns, beginning with the fact that there remains no consensus as to the definition of a UPF.

While the mYFAS is validated for measuring “food addiction,” it does not explicitly target ultra-processed foods. That distinction is crucial: participants were asked about foods like chocolate, salty snacks, and sugary drinks—items that may or may not meet formal UPF definitions.

However, the mYFAS’s most significant flaw is found in the wording of the foods participants are asked to opine upon.

In effect, the study may have measured problematic eating patterns around familiar comfort foods rather than actual “ultra-processed” consumption. This nuance is not explicitly stated in the paper, although the supplementary materials reveal it. Understanding what was truly measured helps clarify how to interpret the results.

Reading Between the Results

The study suggests that addictive-style eating of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) is not rare: about one in eight adults aged 50–80 met criteria for UPFA, with rates rising to one in five among women aged 50–64. Women reported stronger cravings and greater difficulty cutting back than men. Yet these patterns rest on the assumption that the mYFAS captures UPFs specifically rather than any highly palatable foods.

A closer examination of the relationship of self-reported weight to UPFA was more revealing. The researchers found UPFA at every weight perception [1] except “about right” for women, a group that, for any number of reasons besides “addiction,” has disordered eating. Men demonstrated increased UPFA at both slightly underweight and overweight, perhaps reflecting less of a cultural bias towards male eating disorders.

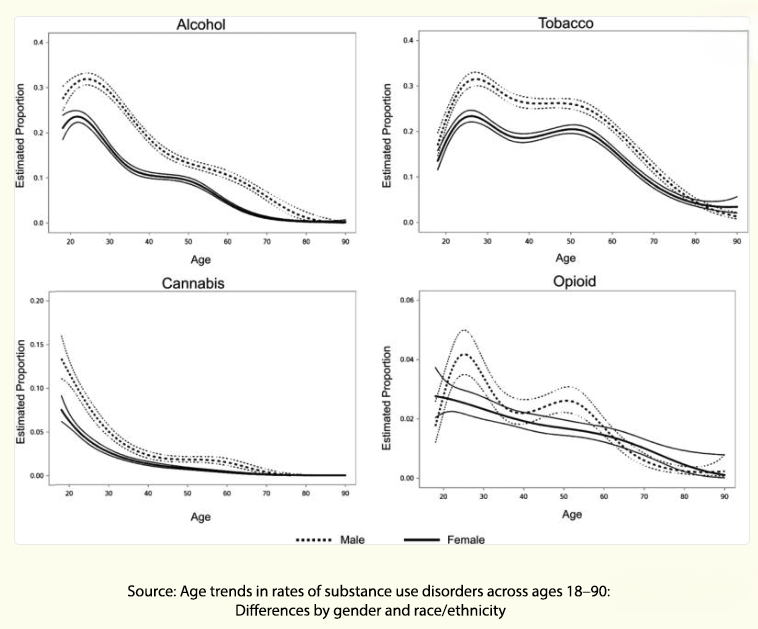

“In the current study, there also appear to be cohort effects in the prevalence of UPFA. Adults aged 50–64 years (15.7%) had almost double the prevalence of UPFA than adults aged 65–80 years (8.2%). Similarly, [alcohol and tobacco use disorders] rates have been found to be higher in those aged 50–64 years relative to those aged 65–80 years.”

Within the confines of the study, which focused solely on those two age groups, the statement is entirely true, adding to the strength of their argument that the tobacco control efforts of Big Food in the 1970s and 1980s were critical. However, the age trajectory of alcohol and tobacco disorders peaks much earlier. Here is a graphic from a study of use disorders by age.

Because only two age groups were sampled, we cannot tell whether this reflects a genuine cohort effect or simply a snapshot.

Finally, there is a perennial chicken-egg problem as the study links addictive-style eating to mental health and social factors. The researchers found that one’s mental health goes hand-in-hand with UPFA. Participants who rated their mental health as “fair” or “poor” were three to four times more likely to show signs of UPFA, as were those who felt socially isolated. The researchers note that there are multiple pathways connecting isolation and UPFA:

“Older adults may consume UPFs to cope with negative effects associated with social isolation, which could then increase the risk of developing UPFA. … Individuals with UPFA report socially isolating themselves to avoid others from seeing how much they eat, which may weaken social networks over time.”

From the researcher's perspective, it is a one-way street from UPFA to isolation. As an emotional eater myself, I get it. Yet causation could run both ways: emotional distress, limited food access, or the challenges of cooking alone may drive comfort eating without implying addiction.

The study’s timing adds another layer of uncertainty. Data collection took place during the pandemic, when social distancing and stress-related snacking were prevalent. These conditions likely amplified reports of cravings and loss of control, making it challenging to separate enduring patterns from temporary behavior.

Context, Confounders, and Causation

The study presents an arresting headline, and the data indicate that many respondents report experiencing symptoms such as cravings and a perceived loss of control over high-palatability foods. Yet several unspoken caveats temper the study’s conclusions.

- Definition drift – The mYFAS tool measures self-reported problems with any highly palatable food; the leap to ultra-processed food addiction relies on an imprecise, still-debated UPF category.

- Sampling scope – While nationally representative for age, sex, income, and education, the survey captures only two broad age bands (50-64 and 65-80), limiting insight into life-course patterns hinted at by substance-use epidemiology.

- Contextual confounders – Data were gathered during the pandemic, when social isolation, stress-eating, and supply-chain disruptions may have all inflated scores.

- Direction of association – The links between poorer mental health, loneliness, and high mYFAS scores could reflect comfort-eating in response to distress as readily as they reflect a distinct addictive disorder.

Where Evidence Ends and Interpretation Begins

The paper provides useful descriptive data on the perceived difficulty of regulating certain foods. Still, its framing of those difficulties as an “overlooked addiction” rests on contested definitions and associations that cannot untangle cause from consequence. Whether you accept the authors’ conclusion hinges on the beliefs and bias you bring to the study, a perception described by artists as the “beholder’s share.” It is up to each reader to decide how convincing the case really is.

[1] underweight, somewhat underweight, about right, somewhat overweight, and overweight.

Source: Ultra‐Processed Food Addiction In A Nationally Representative Sample Of Older Adults In The USA Addiction DOI: 10.1111/add.70186