“An empath is a person who has the ability to feel what others are feeling and understand what others are feeling.”

- Chivonna Childs, PhD

A Modest Boost from mPATH

JAMA recently published a review of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial comparing healthy smokers between the ages of 50 and 77, scheduled for a medical appointment in the near future, who were invited by text or patient portal to participate in a randomized trial of CT lung cancer screening programs (CT LCS), using two different methods. The control arm received a verification of insurance coverage for the CT scan and “enhanced usual care,” advising the patient to speak with their primary physician about CT LCS. The research arm was offered mPATH, a commercial product managed by two of the study’s authors, that seeks to enhance uptake of cancer screening, verifies eligibility for insurance coverage by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and presents a short video to aid patients in deciding to pursue the CT scan. Study subjects randomized to mPATH had a statistically significant, modestly improved uptake of “any” chest CT scan (24.5% vs 17.0%).

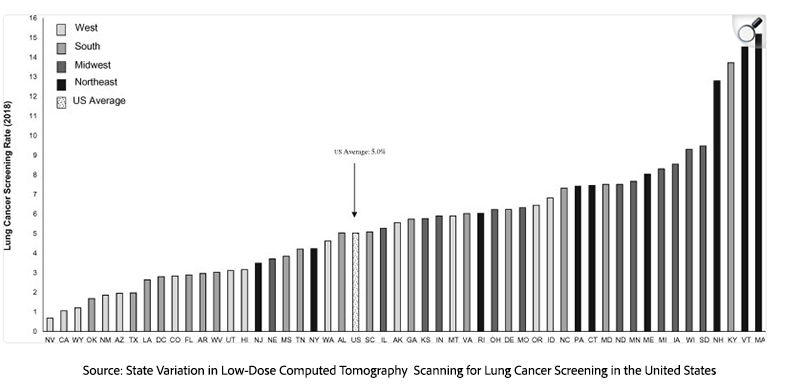

This study is of considerable potential importance. Although CT LCS has been shown to reduce lung cancer (LC) specific mortality and markedly improve survival after LC diagnosis, despite demonstrated benefit and low risk, uptake into CT LCS programs has been generally poor, at 5%, below 1% in some states.

Research into the uptake of CT LCS generally suggests that the solution to improved uptake will lie in improving medical clinic procedural flow. The authors’ demonstration that a digital invitation method somewhat improved uptake of lung cancer screening is good news – but it must be interpreted with caution, based upon a deeper dive into the statistical method employed.

The “Denominator Game”: When Large Populations Shrink to Small Samples

The authors’ method might be considered as an example of what some have called “the denominator game”. The study started out contacting a target population of 26,909 patients (the first denominator) between the ages of 50 and 77, who had a history of smoking in clinic charts, were in reasonable health, and had an appointment scheduled with a personal physician at one of the academic centers. The authors acknowledge “stepwise attrition”. Only 3267 (12%) of those messaged accessed the website and reported their smoking history. The authors acknowledge a decreasing use of patient portal messages at their institutions. And of those, only 1333 (40.8%) respondents (the second denominator) met CMS eligibility and were invited to participate in the study.

Thus, only a small percentage of the estimated 10,978 patients who were CMS eligible, roughly 12% of those eligible, went on to receive any CT scan, i.e., 24.5% in the study arm and 17% in the control arm. In the end, only 245 (2.2%) of the total eligible participants had a screening CT scan (150 in the study arm; 95 in the control arm). [1]

In the final analysis, only three lung cancers were diagnosed by screening. A footnote reveals that five other patients were diagnosed with LC within 16 months; in total, two patients were diagnosed in stage one, two in stage two, one in stage three, and two in stage four - an unfavorable stage distribution for a screening program. In summary, the uptake of a screening of only 2.2% in a target population of 26,909 at two prestigious academic centers, within the context of a research study specifically designed to improve lung cancer screening uptake in their clinics, must be acknowledged as a disappointing result.

It is puzzling that such uptake is considerably lower than that reported in a research survey of self-reported CT LCS participation (20.23%) in NC. Our recent article comments on the unreliability of self-reported CT LCS uptake data.

Given the design of this RCT, one take-home point seems clear. Modifications to medical clinic procedures designed to improve uptake do not appear to offer an immediate solution.

Misinformation’s Role in Depressing Screening Uptake

Are there other factors that might explain the low uptake of CT LCS in NC and offer opportunities for improvement? An alternative hypothesis proposes that the core problem of low CT LCS uptake is a belief by primary care and specialist physicians and their societies that CT LCS offers low benefit and considerable risk, based upon misinformation in published research articles and the guidelines and decision aids that derive from them.

In a recent article, we reviewed the literature on CT LCS. We suggested that low uptake is driven by publications from a relatively small group of US investigators, that have consistently underestimated survival benefits of CT LCS and greatly overestimated harms, repeatedly postulating high rates of overdiagnosis i.e. diagnosis and unnecessary treatment of non-lethal LC, high incidence of false positives, unnecessary procedures and unrealistic modeling of radiation carcinogenesis that suggests that screening CT will cause hundreds of thousands of cancers.

Underestimates of benefit and overestimates of harm have resulted in delays in implementing guideline recommendations and in crafting decision aids for mandatory shared decision-making. The inaccurate information contained in these “aids” tends to dissuade patients and their primary physicians from participation in CT LCS. The design of a prospective trial to test the assumption that true vs. false information would improve uptake of CT LCS presents ethical challenges.

Is there evidence that this dynamic may be at play in NC? What information on CT LCS is currently provided to patients at risk in North Carolina, both in mPATH and in usual care settings, today? In personal communication with the authors, it seems that the research subjects and clinic patients were informed that if they participate in screening and a lung cancer is found, their chance for survival is about 15.6%. The information in the video was slightly different, stating that survival with CT screening was roughly 13%.

In the year 2022, five-year lung cancer survival in the unscreened population in NC was estimated as “below average”, i.e., between 21.3-22.8%. Given the decision aid's far lower suggested survival rate, why would an informed individual participate in a screening program that offers a substantially lower chance of cure? In fact, only 22,4% (150 of 669) who visited the mPATH web page went on to receive a screening CT scan.

What about “usual care” in NC academic centers? In 2021, a group of authors from the University of NC at Chapel Hill concluded that

“Screening high-risk persons with LDCT can reduce lung cancer mortality but also causes false-positive results leading to unnecessary tests and invasive procedures, overdiagnosis, incidental findings, increases in distress, and, rarely, radiation-induced cancers.”

Given such tepid endorsement, it is unsurprising that CT LCS uptake is low at UNC.

The Reality: CT Screening Dramatically Improves Lung Cancer Survival

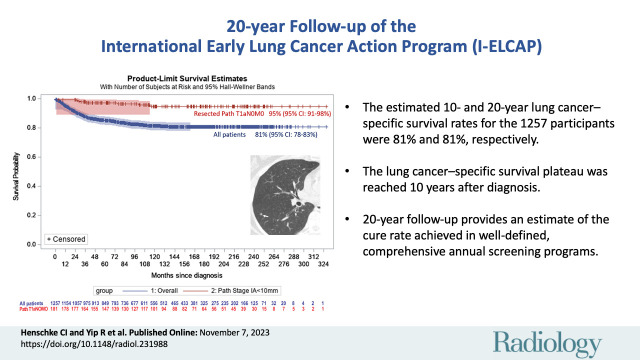

The well-documented reality is that a person diagnosed with lung cancer in an annual CT LCS program has a chance of long-term survival far in excess of 13.6% OR 15.6%. In the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), 400/635 63% were diagnosed in Stage 1 LC and

“The 84.5% 5-year lung cancer-specific survival rate among low-dose CT arm patients with screen-detected stage I lung cancer is higher than the 66.8% rate among those in the same arm with non-screen-detected stage I lung cancer.”

Twenty-year actuarial survival after CT screen diagnosis of LC was 81%

Twenty-year actuarial survival after CT screen diagnosis of LC was 81%

Within this context, the commercial deployment of mPATH DA in clinics - without revision to incorporate accurate information - might be viewed as dissuading those at high risk of LC from being screened and, accordingly, worsening rather than alleviating low uptake into annual CT LCS programs. Each high-risk individual who opts against CT LCS participation and later succumbs to the disease represents a personal tragedy. Persistent low uptake of CT LCS screening due to misinformation will represent an ongoing public health debacle.

When Decision Aids Work Against Public Health

Lung cancer is no longer the uniformly fatal disease it once was—when caught early through annual low-dose CT screening, long-term survival routinely exceeds 80%, a remarkable transformation in outcomes. Yet, persistent low uptake driven by workflow challenges and widespread misinformation continues to place high-risk people in unnecessary danger. Aligning clinical messaging with real-world survival data and strengthening support for screening programs are essential steps toward reducing preventable lung cancer deaths and ensuring that more patients can benefit from today’s dramatically improved prospects for cure.

[1] Uptake of CT LCS among the total group of CMS-eligible patients outside the study is not reported.