In the last few weeks, there has been some drama surrounding black box warnings or boxed warnings issued by the FDA. It takes away one for estrogen, proposes to take another away for testosterone, and applies one to the COVID vaccines. Before reacting based on ideology or instinct, it is worth understanding what this warning actually represents: a label placed at the very top of prescribing information, framed in bold black lines, designed to command professional attention.

To understand why these moves provoke such strong reactions, we first need to clarify what a black box warning is—and what it is not.

What a Black Box Really Is (and Is Not)

It is the FDA’s loudest regulatory voice short of pulling a drug from the market. However, it is because a drug is “dangerous” in the abstract. It is not a verdict but an ongoing weighing of evidence, balancing evidence, uncertainty, and social context. Do the benefits outweigh the risks, or does safe use require heightened awareness, monitoring, or restriction?

All FDA-approved medications are tested in clinical trials involving thousands of patients before approval. After approval, the medication is released into the wild, where physicians may use it more liberally than its indications (off-label use), and the populations being given the drug are often dramatically different than the tested groups, i.e., pregnant women, elderly, or very young individuals, or people with multiple conditions.

As a result, some serious adverse effects emerge only after widespread use. Systems such as the FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and VAERS for vaccines serve as early-warning signals—imperfect but essential—for detecting potential harm. It is within this landscape of incomplete and evolving information that the FDA must decide whether to act.

Crucially, the FDA does not rely on a rigid numerical threshold. Instead, boxed warnings emerge from regulatory judgment—a synthesis of clinical trial data, post-market adverse event reports, mechanistic plausibility, and expert deliberation. As the FDA’s own guidance notes, warnings may be based on observed harms or anticipated harms, such as class effects or biologically plausible risks that have not yet fully materialized in real-world use. The boxed warning is a regulatory hypothesis open to revision.

A black box warning may be issued when risks appear to outweigh benefits, or when serious adverse effects can be mitigated through more targeted use, such as restricting use to specific age groups, avoiding certain drug combinations, or requiring enhanced monitoring. This provisional nature becomes evident when warnings are applied to socially and politically charged therapies.

Hormones, Vaccines, and the Politics of Risk

Hormone therapies have long illustrated the box’s instability. Estrogen warnings expanded dramatically after observational data suggested cardiovascular and cancer risks, only to be later refined as age, formulation, and timing mattered more than initially assumed. Testosterone followed a similar arc: boxed warnings reflected cardiovascular uncertainty, later reevaluated as evidence became more nuanced.

The COVID era compressed this entire process into months. Rare adverse events, specifically myocarditis in young males, triggered intense scrutiny often along politically divisive lines, making it difficult to fashion a warning forceful enough to maintain credibility but not so fearsome that rare risks eclipsed overwhelming population-level benefits.

The Reality of Black Box Warnings in Practice

Practitioners, including pharmacists, encounter boxed warnings embedded at the very top of the official prescribing information, a dense, highly technical document that guides clinical decision-making. In reality, only pharmacists and pharmacy technicians encounter those warnings because they are the ones actually dispensing the medications.

Patients, by contrast, rarely encounter boxed warnings directly. Few prescriptions include full package inserts, and even fewer patients read them. As a result, warnings that dominate regulatory headlines often register as faint background noise in the day-to-day patient experience. Patients typically receive a different, filtered version of drug risk information. If they are lucky, a pharmacist may explain key risks verbally during counseling. More often, prescription bottles carry short distillations, “may cause drowsiness,” or “avoid alcohol

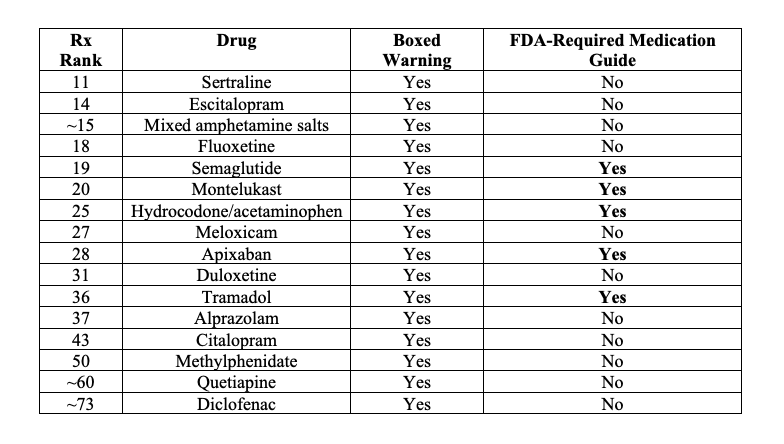

In some cases, patients receive FDA-approved Medication Guides, written in simpler language and legally required when patient understanding is deemed essential to safe use. Crucially, however, not every boxed warning triggers a Medication Guide—leaving many high-risk discussions confined to professional channels. Here is my best attempt to characterize some commonly prescribed medications that have black box warnings and perhaps a medication guide.

This creates a striking asymmetry. Boxed warnings are among the FDA’s most powerful regulatory tools, yet they live primarily in professional spaces. Patients receive a version of the same “risk landscape” that is often lost in translation. Boxed warnings function less as direct patient alerts and more as signals within the healthcare system, shaping what clinicians prescribe, how pharmacists dispense, and what risks are emphasized in conversation. Even this signaling, however, has proven more limited than often assumed.

A 2012 meta-analysis found that these warnings requiring enhanced clinical or lab monitoring modestly reduced new prescribing, more than ongoing use, while specific drug warnings led to greater drops in utilization as prescriptions were changed to alternative medications. They concluded:

“While some FDA drug risk communications have immediate, strong impacts, many have delayed or no measurable effects on health care utilization or behaviors—highlighting how complex it is to use risk communication to improve medication safety.”

In short, even the FDA’s strongest warnings do not reliably translate into changed behavior.

A similar study analyzed 185 of the Medical Guidelines specifically designed for patients. They were written at too high a reading level (10th to 11th grade), lacked clear purpose, summaries, and contextual framing. Comprehension was 50% and further reduced among those with limited literacy. They concluded that they were “of little value to patients.”

The black box is not a label meant to frighten patients. It is a regulatory lever, designed to guide professional judgment under uncertainty. What patients actually hear depends not only on the box itself, but also on how the healthcare system chooses to translate that warning into words, conversations, and care.

Ultimately, the black box is a professional signal, a hypothesis under review, intended to guide clinicians through uncertainty. Its true power lies not in what patients read, but in how physicians and pharmacists interpret and communicate risk in practice.