Both genetics and “environmental risk factors” play roles in our longevity. A group of enterprising scientists used the UK Biobank, a biomedical database containing genetic, health, and lifestyle information from hundreds of thousands of volunteers, pairing genetic data with participants’ self-reported diets.

The dataset included 103,000+ participants, with a mean age of 58, slightly more women than men, and all with two or more “dietary assessments” and without a history of cardiovascular disease or cancer. Like many nutrition studies, the research relied on periodic food questionnaires, an imperfect snapshot of daily eating habits. For analytical purposes, the researchers assumed that these reports reasonably reflected long-term patterns.

Defining Healthy

Those patterns were then characterized as to how well they resembled five “healthy” diets – a group of old friends, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index (AHEI), the Alternate Mediterranean Diet score (AMED), the healthful Plant-based Diet Index (hPDI), the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH), and the Diabetes Risk Reduction Diet (DRRD). Adherence in this British cohort resembled patterns seen in the United States: most people clustered around the middle, following roughly half of the recommended guidelines. Participants were divided into five levels—quintiles—based on how closely their diets aligned with each pattern.

Taken together, this setup allowed researchers to ask a straightforward question: how did diet and genetic predisposition combine to shape survival?

Participants who most closely followed these dietary patterns also tended to be older, better educated, less socioeconomically deprived, less likely to smoke or drink heavily, more physically active, and to have lower body mass indexes—in other words, generally more health-conscious.

What they could not choose was their genetic inheritance.

Using a polygenic risk score—a composite measure that estimates inherited predisposition based on many small genetic variants—the Biobank categorized participants as having low, intermediate, or high genetic likelihood of longevity. Combined with the five dietary adherence levels, this created 15 possible gene–diet pairings for comparison.

Revelations?

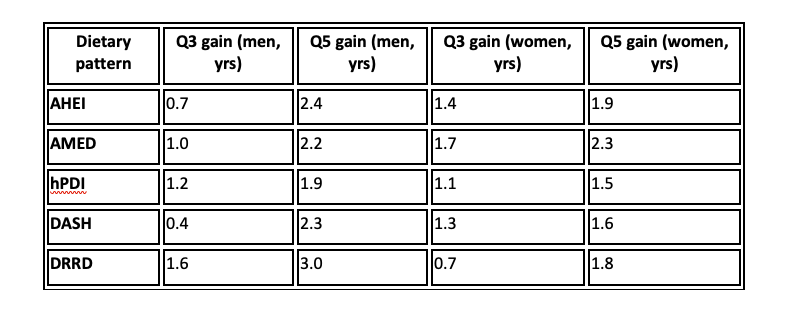

Unsurprisingly, they found that all five dietary patterns reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by about 20%, and that high longevity reduced it by 15%. Translated into life expectancy, men who most closely followed these dietary patterns lived approximately 1.9 to 3.0 years longer than those with the lowest adherence; women gained about 1.5 to 2.3 years. By comparison, a high genetic longevity score was associated with about 1.4 additional years of life for men and 1.7 for women relative to those with low scores.

When favorable genes and strong dietary adherence coincided, the benefits were additive. Men gained up to 3.2 years and women up to 5.5 years compared with those at the opposite extremes. Still, the genetic contribution was modest relative to diet. The findings suggest that, within the bounds set by biology, eating patterns can meaningfully extend life expectancy.

The Fork in the Road

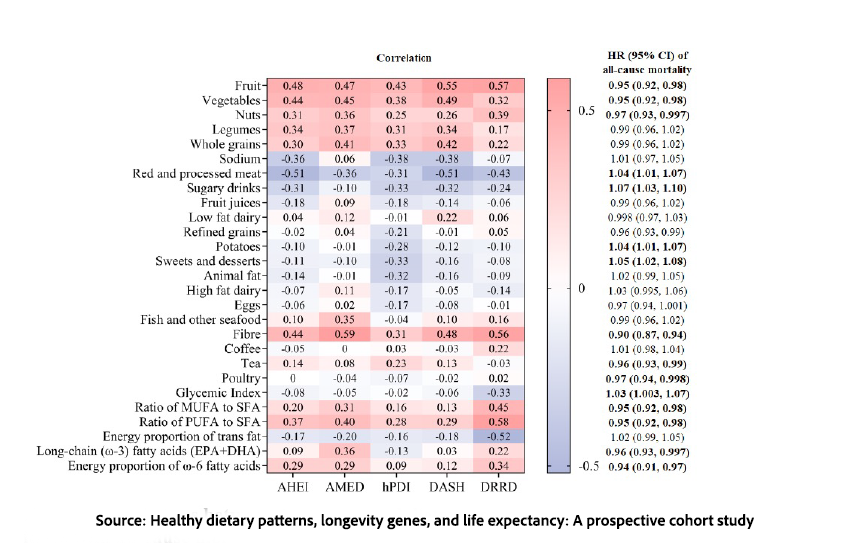

Interestingly, while healthy dietary patterns were associated with longer life expectancy regardless of genetic risk, there was one exception. The Diabetes Risk Reduction Diet (DRRD) showed a strong benefit for those with lower genetic longevity. In seeking an explanation, the researchers pointed to this heat map showing how various dietary constituents affected overall longevity; red indicates reduced all-cause mortality, and blue indicates increased all-cause mortality. [1]

They point to dietary fiber, which has the most impactful of all dietary choices, including fruits and vegetables. I would argue that among dietary fiber’s benefits is better glycemic control, which reduces the long-term risk of diabetes and, in turn, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease. Both, along with cancer, are the top “causes” of mortality.

Notably, alcohol intake did not appear to substantially increase or decrease life expectancy within this analysis, an observation that contrasts with longstanding debates over potential benefits and risks of moderate drinking.

Few people follow any prescribed dietary pattern perfectly. So, what about those of us in the middle, real-world eaters? Using the third quintile (Q3) as a proxy for moderate adherence, the gains were smaller but still measurable.

As you can see, the average American adult, trying to eat “healthy,” does gain some lifespan, but generally only about half of the benefit we might see as dietary warriors.

The Science Says

Following these diets appears to provide a benefit, with an effect size of a year or two additional years of life expectancy at age 45 for men and women, which is meaningful in population health terms. The consistency of the findings across five distinct dietary frameworks strengthens the case that shared features underlie the longevity benefit, rather than any single branded diet. The relationship also followed a dose-response pattern: as adherence increased from the lowest to the highest quintile, so did life expectancy.

The interaction between genetic inheritance and diet, by contrast, was relatively weak. Favorable or unfavorable “longevity genes” did little to amplify or diminish the effects of healthy eating. If genes are only part of the inheritance story, culture may be the other.

Dietary habits are often transmitted across generations through what researchers call food socialization: the passing down of eating practices, preferences, and norms from parents to children. Parents are the primary influence in early childhood, although inevitably, as they grow, peer influence increases and parental control declines. Similar dynamics are often invoked to explain the extended lifespans observed in so-called “blue zones,” where dietary traditions are embedded in daily life.

Research on migrant populations supports this view. When people move to high-income countries, their diets frequently shift toward more energy-dense, processed foods—a transition shaped by acculturation, socioeconomic pressures, and the surrounding food environment.

Longevity is not a genetic lottery ticket we passively hold; it is, at least in part, a behavioral dividend we earn over decades. For individuals in the middle quintiles, you and me, achieving a substantial portion of diet’s benefits does not require perfect or extreme adherence. While genes may nudge the boundaries of possibility, our food culture — the meals we normalize, the habits we inherit, the foods we teach our children to prefer, has a greater impact. The real inheritance influencing lifespan may not be genetic at all, but culinary.

[1] The careful observer will note the deleterious impact of red and processed meats, and the minimal impact of low- and high-fat dairy, despite the new US guidance.

Source: Healthy dietary patterns, longevity genes, and life expectancy: A prospective cohort study Science Advances DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ads7559