Where along the aerodigestive tract does the virus encamp?

The aerodigestive tract consists of the nose, mouth, throat, and lungs. Do the lungs, the primary organ affected by the virus, contain the deadly multitudes? Do they hide in the throat, like a strep infection, or do they reside in our nose and sinus tract?

The virus moves around by airborne pathways involving aerosols, liquid droplets suspended in the exhaled respiratory air. Sneezing and coughing make larger droplets, which travel short distances and fall quickly to the surfaces around us. These bigger droplets, called fomites, were thought to be a source of viral transmission early in the pandemic. Remember wiping down packages and doorknobs?

The virus exists in sizes smaller than one micron, and more recent studies have suggested that it can travel through the air without those large fomites, even upon smaller droplets that stay in the air longer. What is the source of those emitted virus particles, the virions that cause sickness?

The most common test for the virus involves a swab into the nose, collecting a sample of fluid and cells from the nasal turbinates and sinus areas. Even mouth swabs are used in testing. But these sites were chosen because they do harbor the virus, and they are easily accessible. Searching for the virus in our lungs has been, for the most part, a complex and invasive process.

How can we quickly and easily test for aerosols coming from our lungs?

First, a disclaimer. I am a toxicologist, a Ph.D. Doctor of Environmental Medicine, who specializes in aerobiology and inhaled poisons. To be honest and transparent, my company sells and uses machines built in Germany to do environmental and pollution monitoring, equipment that measures airborne environmental particles bigger and smaller than the size of the virus.

The EPA regulates and requires companies to measure and control the polluting gases and particles, based upon their size (PM2.5 and PM10), in the air we all breathe. This is a measurement of environmental pollution. Just as an automobile exhaust pollutes the air, “people pollution,” our exhalations may contribute to the pollutant we call COVID-19.

Measuring “people pollution”

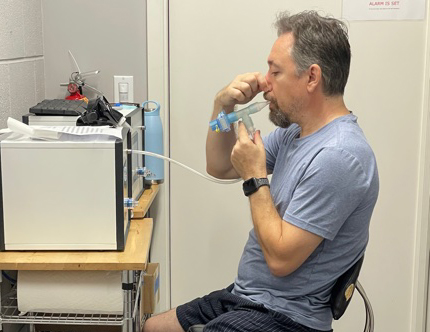

When doing our tests, we first check the measuring device for leaks and purity, and then we inhale air that has passed through a High-Efficiency Particle filter (HEPA). Breathing normally, we exhale through a mouthpiece assembly. The machine collects the lung exhaled gas mixture, dries it by heating, then counts and measures the particles using the intense white light of a spectrophotometer.

When doing our tests, we first check the measuring device for leaks and purity, and then we inhale air that has passed through a High-Efficiency Particle filter (HEPA). Breathing normally, we exhale through a mouthpiece assembly. The machine collects the lung exhaled gas mixture, dries it by heating, then counts and measures the particles using the intense white light of a spectrophotometer.

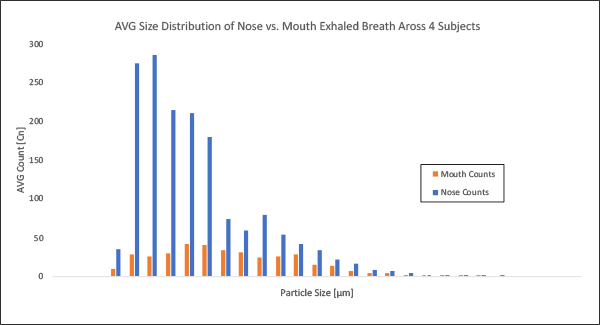

The graph shows the pattern we found in my laboratory. It is bimodal with peaks of two sizes, both far below the 2.5 microns of PM2.5. The particles we exhale are in the ultrafine range, much like most of the outdoor air particles that come from burning wood and auto/truck exhaust.

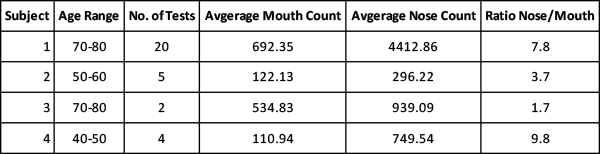

In some preliminary studies on healthy individuals [1], we separated the air exhaled from our lungs, the lower portion of the aerodigestive tract that comes out of our mouth, from the exhalations coming from our nose, the uppermost portion of the tract. There appear to be more particles in the emitted air from the nose than from the mouth.

Subject to verification and additional research, the air emitted from our nose appears to contain more particles, per unit volume, than the air we exhale from our lungs. Suppose a person is infected with the virus and has active viral replication sites in their nasal cavity. In that case, infectious aerosol particles may occur at increased numbers from this exhaust source.

By implication, there is likely to be a more significant emission of infectious particles from the nasal openings in virus-positive persons, symptomatic or not, vaccinated or not. If masks are well fitted and acting as effective filters while being conscientiously worn, both exhaust streams will be cleaned, and the emitted air rendered less infectious.

Fewer particles in the emitted air, healthy or sick, mean that there would be fewer virus particles emitted and, therefore, a lower risk of transmission. Not zero but unlikely to be a significant risk even if “some” virus may be present.

Our use of masks is not perfect!

Few, if any of us, wear custom-fitted masks. When wearing glasses and a mask, who rarely or never complains that their lenses fog up now and then? This suggests that the leaks are most likely to occur along the mask junctures below the eyes, the sub-orbital cheeks. More importantly, how often have we seen a person wearing a mask to cover their mouth, but not their nose? Our work suggests that the exhalations emitted by our nose are an important source of viral transmission, and covering our nose greatly increases the efficacy of protective masks, and perhaps, all face coverings.

Practice Environmental Medicine

Protect the health of others.

Wear a mask in crowds!

Get Vaccinated too!

[1] The four test subjects were all males; the table lists their age ranges.