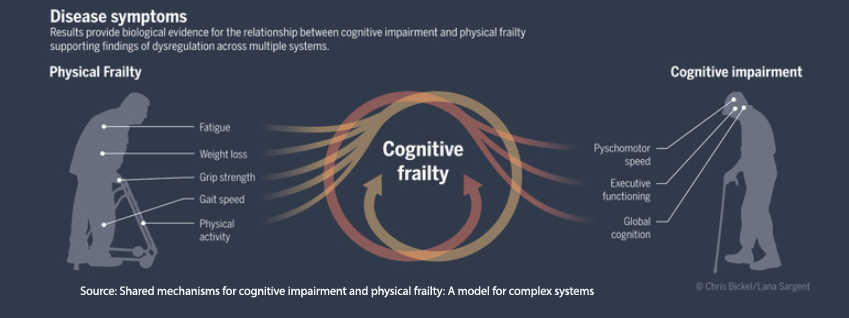

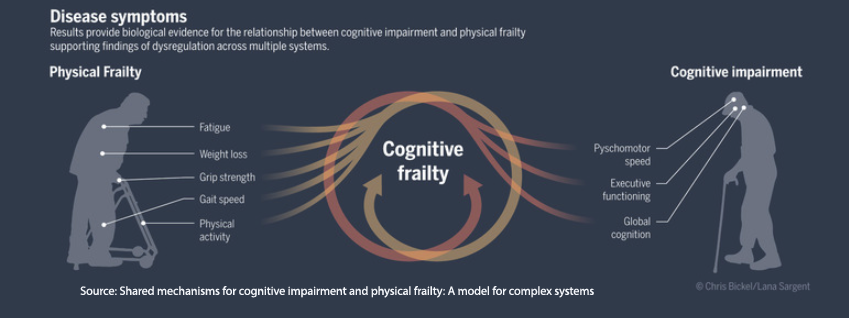

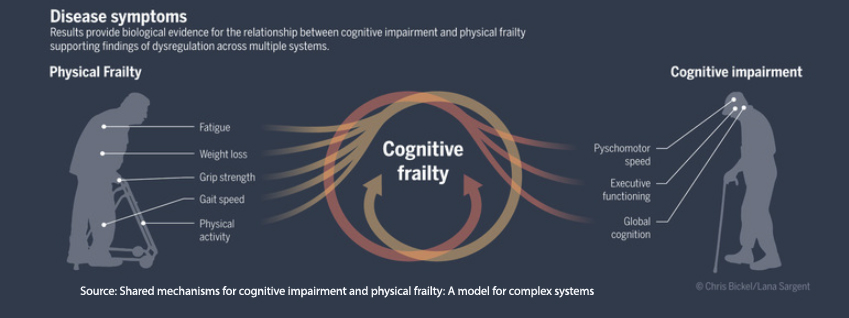

Aging has never been a more discussed and, at times, contentious issue. The narrative of the spry has given way to those living in the Blue Zones, which in turn has been replaced by increasing concerns over the inevitable (?) failing of physical and mental prowess. Business Insider is now referencing the economic “peak burden” as the Boomers, the largest of all generations, all become over 65. Two phrases increasingly used are “frail” and “cognitive impairment.” Our scientific understanding indicates that these are both separate and entangled in the process of aging.

Frail

The term is defined in terms of physical attributes – the slowing of our gait, a decrease in muscle mass and strength, a more chronic sense of fatigue, and, in some instances, weight loss as our metabolic machinery fails  us. For the most part, frailty is readily observed and quantified. A meta-analysis of surgical patients demonstrated that these measures of frailty could identify individuals at greater risk for postoperative complications and death. Among those specific complications was postoperative delirium – a generally transient state of confusion, disorientation, and cognitive dysfunction characterized by disturbances in attention, awareness, and perception.

us. For the most part, frailty is readily observed and quantified. A meta-analysis of surgical patients demonstrated that these measures of frailty could identify individuals at greater risk for postoperative complications and death. Among those specific complications was postoperative delirium – a generally transient state of confusion, disorientation, and cognitive dysfunction characterized by disturbances in attention, awareness, and perception.

Cognitive Impairment

It might be helpful to think of cognitive impairment as a more persistent version of delirium. It can range from the undetectable [1] to the noticeable to dementia. Unlike frailty, it has several components, few easily quantified. They include impairment or reduction in:

- Memory for both short and long-term events.

- Sustaining attention and focus for extended periods.

- Executive function in processing information, problem-solving, making decisions, and following up on those plans.

- Language in conveying and understanding spoken and written words.

- Visuospatial skills involved in simply moving through your daily environment.

- Motor skills involving both the smaller muscles, e.g., buttoning a shirt, and the larger muscle groups involved in balance and walking.

In reality, these two terms describe two sides of the same coin, so it is perhaps worthwhile to see how they interact.

In another meta-analysis examining the relationship between cognition and frailty, researchers found that slowness and muscular weakness were the most common findings of frailty. At the same time, memory was the most frequent cognitive impairment seen in 30% of the frail. Of greater interest might be that

“The executive functions, verbal fluency, attention, commands, language and judgment were associated in 10% of these studies.”

This supports the idea that frailty is different but not wholly distinct from cognitive impairment and vice versa.

Frailty as a verb

The initial definition of frailty describes outcomes, but in another sense, considering frailty as a state of increased vulnerability to stressors offers a lens into its underlying causes. Researchers have identified over 400 proteins and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) predictive of frailty and cognitive impairment. Working backward from those biological changes were multiple cardiovascular risks, e.g., diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia (an elevated "bad" cholesterol), and alterations of “neuroinflammatory proteins.”

Aging involves changes over time, so one theory used to explain these deleterious impacts and the rising incidence of cancer as we age is a “deficit accumulation,” when the wear and tear exceed the ability to recover or repair. Those individuals with greater reserve or ability to tolerate age-related changes or damage do better; they are the spry. Another term used to describe this accumulated stress is allostatic load, the cumulative impact on various bodily functions, including cognition and muscle strength.

The discourse on aging is evolving frailty, characterized by observable physical attributes, is not merely an outcome but a state of heightened vulnerability rooted in biological changes, including cardiovascular and neuroinflammatory factors. Cognitive impairment, ranging from subtle deficiencies to more pronounced issues, overlaps significantly with frailty.

The relationship between frailty and cognitive impairment is reciprocal, with each influencing the other, and their relative importance varies among individuals. Individuals with more significant reserves tolerate age-related changes better. Acknowledging the complexity of this interplay is crucial for understanding our increasingly aged society.

[1] Early confusion and disorientation can often be covered over. For example, someone with mild cognitive loss may well know how to successfully navigate the kitchen and make a meal until you suddenly move the silverware to a different drawer, and they can no longer find those utensils.

Source: Association Between the FRAIL Scale and Postoperative Complications in Older Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Anesthesia and Analgesia DOI: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006272

Shared mechanisms for cognitive impairment and physical frailty: A model for complex systems Alzheimers Dementia DOI: 10.1002/trc2.12027

Relationship between cognition and frailty in elderly: A systematic review Dementia Neuropsychologia DOI: 10.1590/1980-57642015DN92000005