Science Progresses One Funeral at a Time – Planck’s principle [1]

Science advances – slowly. Yet, once scientists accept a novel theory as proven or established, it’s rare to revert backward to a thoroughly discredited approach. Occasionally, however, it has happened, and the public suffers. Interestingly, usually, those advancing “Luddite” science are politicians touting some socially acceptable (or lucrative) theory appealing to their constituencies.

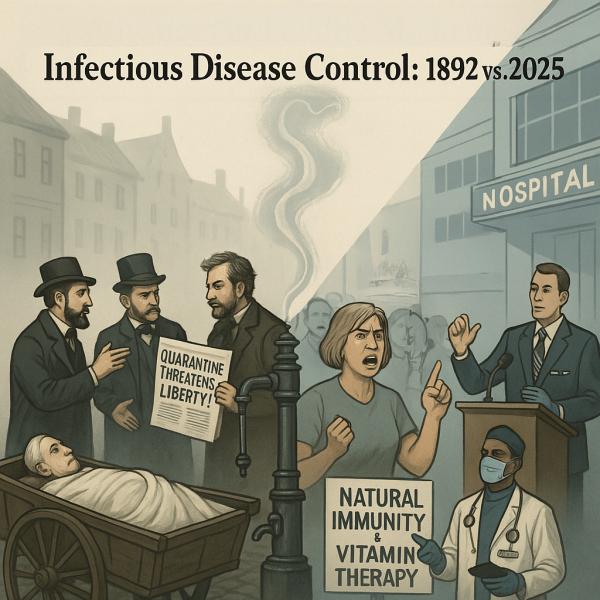

For some reason, the reversionary science movement led by politicians (and physicians seeking to gain or retain status or profit) seems to harbor a dislike for the germ theory of disease, customarily opposing masking, quarantines, or vaccines to prevent transmission. Instead, reactionary groups favor vitamins, nutrition, or wellness programs as solutions or cures. Far be it from me to raise objections here; I come not to bury these views nor to champion them; I simply wish to share history, notably one of the most devastating epidemics of all time – which in some ways seems eerily familiar:

The Hamburg Cholera Epidemic

Hamburg’s Cholera visitation of 1892 began in early August before, a few weeks later, sneaking aboard shipping vessels bound for America. There, the germ, along with the passengers carrying it in their guts, disembarked, causing havoc and death on American shores. Like the Chinese, who failed to disclose the COVID-19 outbreak in a timely manner, the Hamburg authorities kept the outbreak hidden for weeks. [2]

What at first seems odd regarding the 1892 cholera epidemic is it only affected Hamburg. Every other European country managed to evade it, a testament to scientific advances that were formally incorporated into public health and fostered by governmental actions as early as 1884.

The modern approach began in 1854 when Queen Victoria’s anesthetist, John Snow, discovered that cholera was spread through the water supply, transmitted by drinking contaminated water, and urged the London Health Board to remove the handle at the Broad Street well, despite loud objections from his opponents, the miasmatists. Almost miraculously, the epidemic was quelled. The success of the intervention put a dent into those touting the prevailing miasma theory, believing that cholera was transmitted by noxious mists enveloping the ground and surrounding houses, mainly of the poor, the intemperate, the dirty (and in the US, the immigrants). After Snow’s discovery, the British took immediate steps to curtail sewage disposal into the drinking water system, introducing advanced sanitation measures, including draining the Thames and instituting water purification systems. But while Snow knew how to stop the spread, he still didn’t know what caused the disease).

It took another 17 years for the culprit to be identified. In 1883, the German scientist Robert Koch identified the bacillus that caused the disease, proving that germs, not ghost-like vapors, caused cholera. Koch also came to believe the germ was water-borne and that quarantine, along with filtering the water supply, was necessary to prevent transmission. The enlightened took note, and proper public health precautions were instituted in most of Germany. Koch became the dominant force in the new science, training doctors and health professionals who eagerly embraced his approach. Unsurprisingly, the disease never again reached epidemic proportions in Europe, except for Hamburg.

The More Things Change….

Hamburg, today a three-hour car ride from nearby Berlin where Koch was experimenting, teaching, and expounding, boasted Koch’s major nemesis: Dr. Max Von Pettenkofer, who, together with his allies, waged all-out attacks on Koch and his theories. By early August, some physicians suspected an epidemic was brewing and began to question the miasmatic approach. Koch was dispatched to Hamburg in mid-August and attempted to impose sanitary measures, including the boiling of drinking water and the installation of a water filtration system. His efforts were rebuffed until the disease overran Hamburg, and some 8500 people died.

The politics of the day didn’t help. Richard J. Evans, in his exhaustive treatise, Death in Hamburg, notes the laity, most notably the merchant class, opposed quarantines on economic grounds, and the political fringes claimed a new Epidemics Bill which included enforced quarantines grossly violated personal freedoms, and “contained unbelievable attacks on personal freedom, on trade, and on economic life in general.”

It's the Diet, Stupid

Opponents of Koch’s bacterial theory of disease, including Pettenkofer’s followers, ravaged him, calling him a fanatic and attacking the “modern surfeit of bacteriology.” Those who believed cholera was carried through the air diverted attention from medical management to focus on environmentalism. Other groups argued that the 1892 epidemic was a consequence of the local diet, which, although not ultra-processed, was “too fatty, and the inhabitants drank too much.” One Social Democrat decried the practice of chemical disinfection as a ruse fostered by the chemical industry. Echoing Dr. Pettenkofer’s views, some advocated “exposure to [fresh] air [and] sunshine” as the cure-all instead of boiling the drinking water and filtering the water supply.

Pettenkofer’s views, espoused by his students and allies, especially one Rudolf Emmerich, refused to die, as had Pettenkofer, who committed suicide in 1901. The science even became a legal controversy when a court was asked to determine whether contaminated water or miasma was responsible for a 1901 typhoid outbreak. Prosecutors had brought criminal charges against the Gelsenkirchen Waterworks for dispensing contaminated water, claiming the water was responsible for the outbreak, and called Dr. Koch as its expert witness. The defense claimed it was a miasma and had nothing to do with the water and called Dr. Emmerich to testify on their behalf. After accounting for misstating the facts in a public lecture so as not to rile the public (sound familiar?) Koch testified that waterworks provided untreated water, which caused the outbreak. At the end of the day (actually two and a half years), the court, overwhelmed by the science, punted. Instead of facing jail time for dispensing tainted water, the defendants were fined for providing adulterated food under an 1879 statute. (The defense argued water wasn’t food, but the court didn’t buy it). The decision didn’t stop the Miasmatists from meowing, and the controversy wasn’t finally settled until years later, enabling the opponents of the proven germ theory science to divert attention to other concerns.

Diversionary Tactics

While Koch’s medical model addressed many of the epidemics of the day, by the end of the 1890s, Germany’s political strategy of Weltpolitik (aggressive territorial expansion and military buildup) “took medical attention away from epidemics and refocused it on the problem of the [declining} German birth-rate. …Reforming officials in Berlin were increasingly concerned to counteract the tendency … by educating the public in their national duty to have children….”

Everything old is new again—especially the mistakes.

Studying the past reminds us that resistance to scientific consensus often hides behind the same, ever-repeating noble-sounding ideals—be it personal freedom, natural living, or distrust of “chemical” cures. As in Hamburg, the allure of alternative explanations can be strong, especially when they flatter our instincts, soothe our fears, fatten our pocketbooks, or pay homage to homeopathic naturalism. But when policy leans on popular sentiment over hard and proven evidence, history has shown us where that path leads—and it rarely ends well.

[1] Widely attributed to Max Planck, his actual statement was, “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die.”

[2] Of course, anyone who read the Hamburg newspapers, including the US consul whose job it was to monitor local diseases and prevent ships from leaving an infected port, might have realized cholera had broken out two weeks before the official announcement - thereby preventing at least one ship from embarking.

Source: Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg