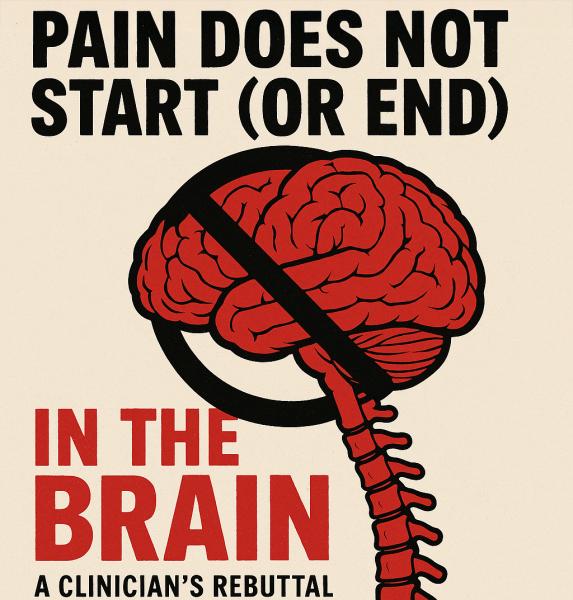

Sanjay Gupta’s new book, It Doesn’t Have to Hurt, arrives with a breezy promise that will sound, at best, naïve to people who wake to severe pain every day. In his recent media interviews, Gupta casts pain as something that “begins in the brain,” a framing that risks sliding from nuance into the old stigma that pain is “in your head.” That’s not just misleading—it can be harmful when clinicians take it as a universal rule.

Pain Science 101: Experience vs. Generator

Yes, the conscious experience of pain is constructed by the brain; without a brain, there is no felt pain—just as there is no felt love. But the generators of pain commonly arise in the body (periphery) and transmit nociceptive signals through the dorsal horn and ascending pathways before they are interpreted centrally. That distinction—experience versus generator—is foundational.

Consider a kidney stone, where obstruction in the ureter produces agonizing signals that are transmitted to the brain but certainly do not “begin” there. The same is true with a fractured bone: tissue injury activates nociceptors and inflammatory mediators that fire signals upward to be interpreted. In spinal stenosis, mechanical compression and ischemia of nerve roots drive neurogenic claudication that has nothing to do with an originating cortical event. Osteoarthritis, likewise, begins in joint pathology—such as synovitis, cartilage breakdown, and nerve growth factor signaling—which may evolve into central sensitization but starts in the periphery. Even in conditions Gupta himself references, such as irritable bowel syndrome, the story is one of interplay between peripheral visceral hypersensitivity and central processing rather than pain mysteriously materializing in the brain.

To claim or imply that pain “begins in the brain” erases these well-established pathways and invites patients to be second-guessed. Even CBS’s news segment unintentionally undercuts the brain-first mantra: Gupta’s own mother’s severe pain from a vertebral compression fracture dropped from “100 to about 3” immediately after surgical repair, when the peripheral pathology was corrected. Treat the cause; the cortex will follow.

“Treat the Brain First?” That’s Not How Board-Level Pain Medicine Works

Gupta has suggested that because pain is processed in the brain, we should “treat the brain first.” That’s an overgeneralization. In board-certified pain practice, we match treatments to the dominant mechanism—peripheral, neuropathic, visceral, inflammatory, central, or mixed—then layer biopsychosocial supports. For central pain states—such as some cases of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) or migraine—brain-directed therapies are crucial; for stone colic, spinal stenosis, or inflammatory arthritis, brain-first alone would be substandard care.

Mindfulness Does Not Equal Morphine

Gupta’s recent Washington Post interview flirts with the claim that mindfulness “can be as effective as opioids.” Mindfulness, CBT, distraction, and related strategies are valuable tools—I recommend them myself. But promotional equivalence to opioids blurs indication, intensity, and time course. There are no robust head-to-head trials showing mindfulness reliably matches clinically appropriate opioid analgesia across moderate-to-severe nociceptive or neuropathic pain. In real clinics, mindfulness is an adjunct, not a replacement, and certainly not a one-size-fits-all substitute when tissue injury or nerve compression predominates.

Foam Rolling, Distraction and Other “Joy Snacks”

Gupta states foam rolling, touch, and placebo-responsive pathways as evidence of the brain’s power. These can help some musculoskeletal pains—but try telling a patient with CRPS, migraines, or an IBS flare that foam rolling is their fix. Mechanisms in these conditions include autonomic dysregulation, trigeminovascular activation, neuroinflammation, visceral hypersensitivity, and central amplification—complex biology that may require disease-specific pharmacology, procedures, or surgery alongside behavioral supports.

“Most People Can’t Recall the Event That Started Their Pain”

This claim misleads, even if the point of it is to emphasize pain’s subjectivity. Much chronic pain does not begin with a memorable trauma—because osteoarthritis, spinal stenosis, and IBS typically emerge gradually from biologic, degenerative, inflammatory, or immune processes. The absence of a single trigger does not make pain psychogenic; it reflects the disease’s natural history.

Why This Matters: Stigma and Clinical Harm

When a high-profile physician leans hard into “the brain is where pain begins,” the public often hears an old slur: your pain is in your head. That can legitimize dismissing patients who don’t respond to brain-first advice as lacking willpower, and it can rationalize withdrawing needed multimodal pain care. The National Academy of Medicine has already warned about harms from undertreating pain while oversimplifying solutions. We shouldn’t replace one simplistic narrative (opioids fix everything) with another (mindfulness fixes everything).

A Better Message

Pain is a biopsychosocial experience with biologic generators. Start with mechanism. Fix what’s fixable in the periphery, manage what’s not with evidence-based pharmacology and procedure when indicated, and always add brain- and behavior-based tools as adjuncts. That’s how you honor science and the lived reality of people in serious pain.

Gupta’s media tour has the right aspiration—compassion and curiosity—but the repeated “brain-first” shorthand is reductive. People in pain deserve better than slogans. They deserve care that is accurate, individualized, and free of stigma.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a pain and addiction medicine specialist and serves as Executive Vice President of Scientific Affairs at Dr. Vince Clinical Research, where he consults with pharmaceutical companies. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Deconstructing Toxic Narratives–Data, Disparities, and a New Path Forward in the Opioid Crisis, to be published by Springer Nature. He is not a member of any political or religious organization.