Everyday environments, extraordinary stress

For most people, the buzz of fluorescent lighting fades into the background, the chatter of a cafeteria blends into ambient noise, and the scratch of a shirt tag is a fleeting nuisance. However, for many individuals on the autism spectrum, these same sensory inputs are magnified — much like trying to focus on a conversation while a siren blares nearby or a strobe light flickers in their eyes.

In my clinical practice, I’ve seen firsthand how environmental stressors can drive anxiety, panic, or emotional shutdown. In one case, simply replacing a flickering bulb resulted in a dramatic decrease in a child’s daily distress. In another, an open office with constant interruptions was overwhelming; moving to a quieter cubicle restored productivity and calm.

These examples underscore a simple but powerful truth: for many individuals, mental health is profoundly shaped by the sensory world.

Autism and sensory processing: more than a side note

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is typically described in terms of social communication differences and repetitive behaviors. But equally important, though often overlooked, are differences in sensory processing.

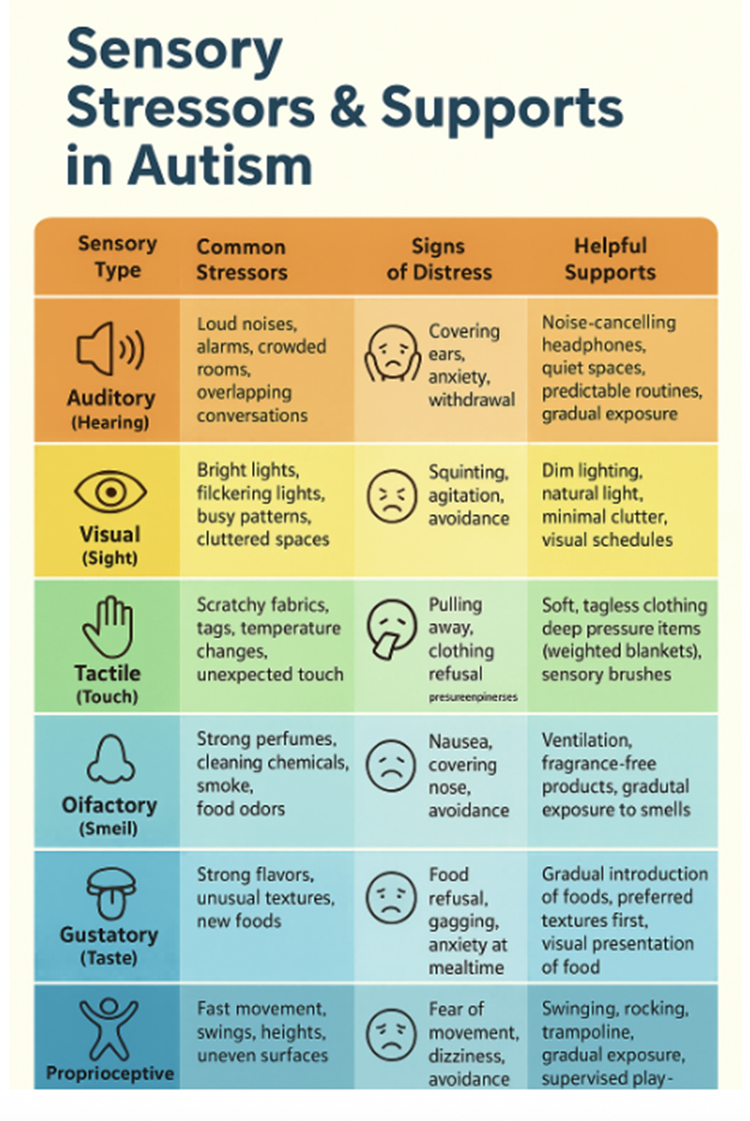

The DSM-5, the manual used by clinicians to diagnose autism, includes “hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input” as a core feature. This can manifest in many ways:

- Covering ears at loud sounds that others barely notice

- Avoiding specific clothing or food textures

- Seeking intense sensations, like spinning or watching moving patterns

- Being unusually sensitive to changes in temperature, smell, or lighting

Research suggests that over 90% of individuals with ASD experience sensory differences that affect daily life. These differences are deeply tied to stress, coping mechanisms, and overall quality of life.

Sensory overload harms mental health

Mental health challenges like anxiety, depression, and burnout are common in autistic individuals. While multiple factors, including stigma, social exclusion, and limited access to tailored care, play a role, sensory overload is a critical, underappreciated driver.

When the environment bombards the nervous system with unwanted stimuli, the body mounts a stress response: heart rate increases, muscles tense, and cortisol levels surge. For someone with heightened sensory reactivity, this stress can be near-constant.

Over time, sustained overload can lead to chronic anxiety, which, when exceeding the body’s ability to cope, leads to shutdowns or meltdowns, where withdrawal, mutism, or intense outbursts are the only solution. Disrupted sleep from noisy or overstimulation, along with constantly “masking” distress, results in exhaustion and burnout, often requiring months of recovery.

This connection between sensory stress and mental health underscores the importance of environmental design.

How environments can hurt

Everyday settings can be unexpectedly harsh for autistic individuals. Fluorescent lights, flickering screens, and glaring white walls create constant visual strain. Background noise from open spaces, echoing rooms, or crowded transport adds to the overload. Even a light touch, like a clothing tag or coarse fabric, can feel unbearable. Scents from perfumes, cleaning products, or food linger too strongly, and unpredictable changes in routine or setting make it difficult to feel settled.

The cumulative effect is what many autistic self-advocates call “sensory assault”—a daily barrage that erodes well-being.

How environments can help

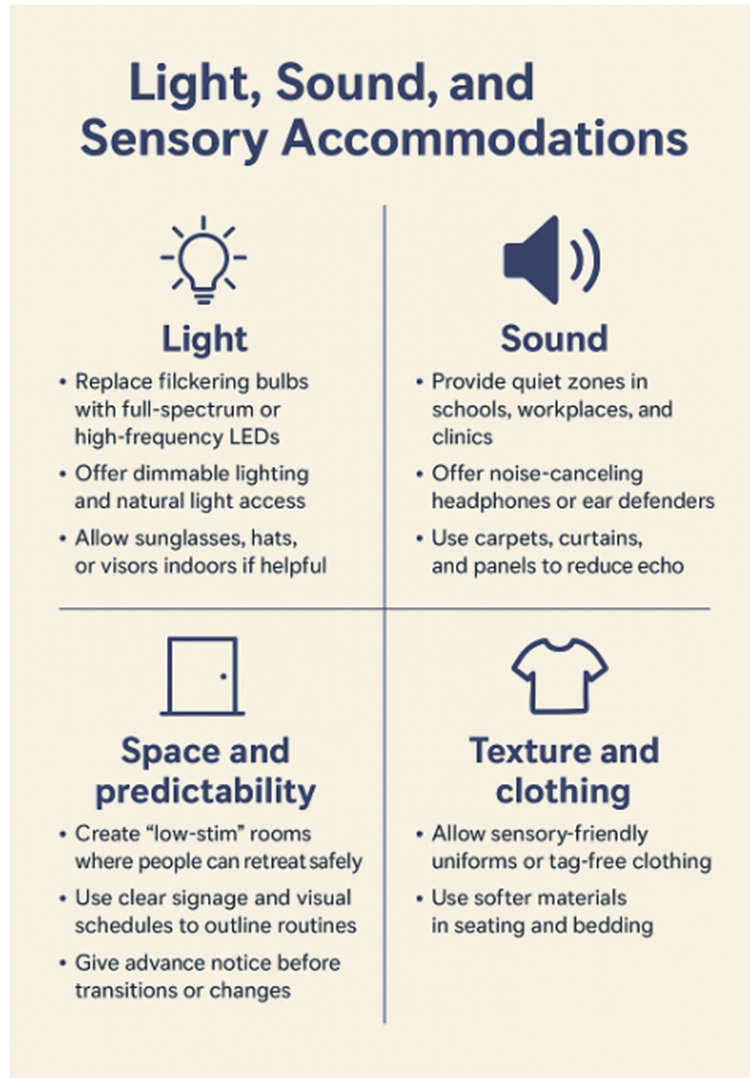

The encouraging news is that thoughtful changes often bring rapid relief. While sensory accommodations vary from person to person, a few principles consistently reduce distress and promote mental health.

These are not luxuries—they are evidence-based supports. Studies show that when sensory stress is decreased, autistic individuals often exhibit fewer “challenging behaviors,” better emotional regulation, and improved participation in school and work. However, what calms one person may overwhelm another.

Across schools, workplaces, and healthcare settings, sensory-aware design is quietly transforming daily life. In many school districts, “sensory rooms” now offer weighted blankets, swings, and calm lighting—spaces where overstimulated students can reset. Teachers are increasingly using visual schedules to make transitions more predictable, and students report lower anxiety levels and stronger classroom engagement as a result.

Employers, following guidelines from the Job Accommodation Network (JAN), have adopted simple adjustments such as providing noise-canceling headphones, offering flexible breaks, or creating private cubicles. These small changes have been shown to significantly boost both productivity and employee retention among employees with autism.

Healthcare settings are evolving. Clinics that reduce waiting room noise, add visual communication boards, and structure visits more clearly have observed fewer meltdowns and smoother patient interactions.

These efforts highlight a broader truth: sensory-informed environments don’t just support autistic individuals—they make spaces calmer, more welcoming, and more functional for everyone.

What science does and does not tell us

Research consistently shows that the environment matters. Yet, science also makes clear that individualization is essential. What soothes one person may overwhelm another—some thrive under bright light and soft music, while others need quiet and dimness to feel comfortable.

The evidence on sensory integration therapy, which utilizes structured sensory activities such as swinging, brushing, or weighted play to enhance regulation and focus, is mixed. This approach is commonly employed in pediatric care. Some studies have shown positive effects, but the results are inconsistent. The American Academy of Pediatrics advises that such therapies should be goal-oriented and used thoughtfully, avoiding sweeping claims of universal benefit.

Emerging research is beginning to explain the biological roots of sensory differences. Studies of the autonomic nervous system suggest that individuals with autism often experience heightened physiological reactivity, which may explain why sensory overload feels so intense. Neuroimaging has also identified differences in brain regions responsible for filtering and integrating sensory input, providing tangible evidence of hypersensitivity.

Still, significant gaps remain. Most existing research focuses on children rather than adults, and high-quality trials testing specific environmental modifications are scarce. Understanding how to design truly inclusive spaces will require more comprehensive and rigorous studies.

Practical steps for families, clinicians, and communities

1. Map triggers and supports

Keep a brief daily log to identify patterns that lead to distress or restore comfort. Use these insights to guide environmental adjustments.

2. Adjust the environment first

Before labeling behavior as resistance or mood-related, check for sensory overload. Modify lighting, sound, or routine structure to reduce overwhelm.

3. Develop an Individualized Sensory Support Plan

Work with the individual to identify which sensory inputs are calming and which are overwhelming, and outline specific supports such as headphones, fidget tools, sensory breaks, or quiet retreat spaces. Encourage autonomy by allowing the person to step away from stressful environments, make choices about which coping tools to use, and manage their sensory comfort independently. Support self-advocacy by teaching the communication of sensory needs through speech, assistive devices, or visual signals, and encourage strategies such as deep breathing, mindfulness, or requesting breaks. Train staff, peers, or caregivers to recognize sensory cues and respond respectfully, creating an environment that balances structured support with personal choice and control.

4. Plan for crises

Establish predictable, respectful responses to sensory distress. Define safe spaces, contacts, and signals for help, and rehearse these steps regularly to reduce anxiety during real events.

By systematically implementing these strategies, families, educators, and advocates can profoundly improve daily comfort, well-being, and mental health for individuals with autism as they navigate sensory-rich environments. Designing sensory-smart environments benefits individuals with ADHD, PTSD, anxiety disorders, or migraines when light, sound, and space are managed thoughtfully. Even neurotypical people find calmer, quieter spaces less stressful. When we design with the most sensitive in mind, we improve well-being for everyone.

Sources: Autism Speaks About Autism Spectrum Disorder, CDC, Autism and Sensory Processing National Autistic Society