Humans are storytellers. In an age when social media has exponentially amplified storytelling, stories provide the common narrative for civilization’s cultures, sharing in our evolution as much as genetics and niche. Stories renew and refresh memories. A new study in the Journal of Neuroscience investigates just how a story’s content shifts how it is remembered.

The Science of Stories

Memories are layered reconstructions: they include a story’s main events, its overall structure, and peripheral details that enrich it with color and context.

When memories are formed, the hippocampus, a brain structure critical for integrating different types of information into a single memory trace, flexibly engages with other brain regions, particularly those within the default mode network (DMN). The DMN is an extensive, interconnected network of brain regions that is particularly active when an individual is not focused on the external world, when we meditate, rest, or ponder aimlessly. Prior studies have indicated that some connections between the hippocampus and DMN are associated with emotional and evaluative aspects of memory, the conceptual details, the analytics, and emotional responses. Other portions of the hippocampal network appear more involved with perceptual elements of memory, e.g., the sights and sounds.

The study explored whether differences between conceptual and perceptual storytelling arise during memory formation or only later during recall. To test this, researchers crafted short narratives about everyday events that shared the same core details but differed in their added context—some emphasizing sensory detail, others reflective meaning. Using fMRI brain scans, they observed distinct hippocampal connectivity patterns for the two story types, suggesting that the kind of detail surrounding an event changes how the brain encodes and later retrieves it. To see how these differences played out in practice, the team built stories designed to tease apart concept and perception.

Experimenting with Narrative

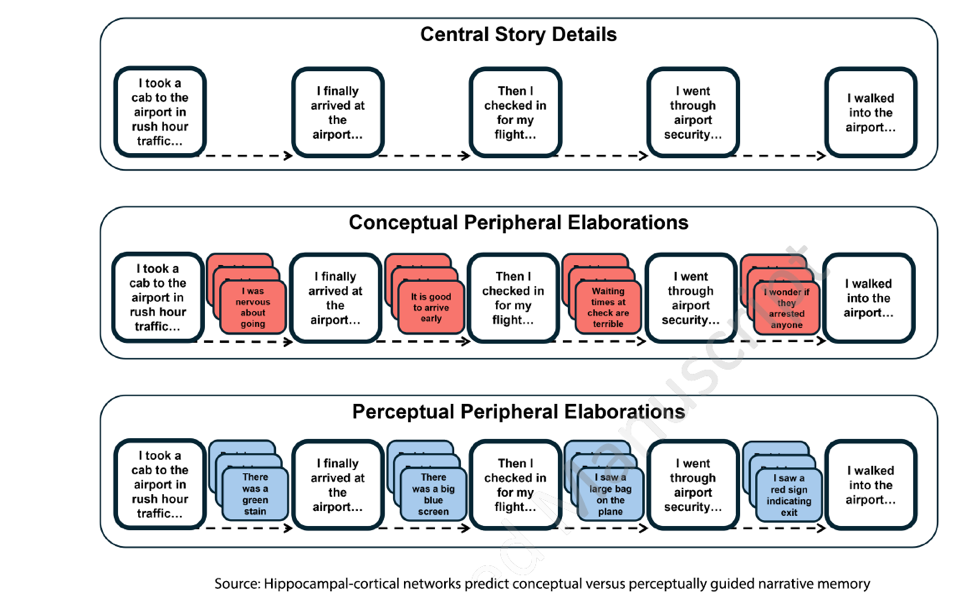

The researchers created three stories based on everyday events: "Going to a Restaurant," "Taking a Flight," and "Getting Groceries." Each story had 14 consistent details forming the narrative, but differed in the 42 “elaborative details.”

The researchers created three stories based on everyday events: "Going to a Restaurant," "Taking a Flight," and "Getting Groceries." Each story had 14 consistent details forming the narrative, but differed in the 42 “elaborative details.”

- Conceptual Details - those that describe analytic or emotional responses tied to a central detail. For example, in the restaurant narrative, a central detail, "The host brought us to our table on the patio," a conceptual detail would be: “The patio was actually up on the rooftop of the restaurant, which was a pleasant surprise”. [emphasis added]

- Perceptual Details - describe something experienced with the senses (sight, sound, taste, touch, smell). Statements were designed to describe associated objects, people, and sights in the external environment. Using the previously mentioned central detail, the perceptual detail would be "I noticed the wooden arm of the chair was chipped in a few spots". [emphasis added]

During fMRI scanning, thirty-five adults listened to full versions of these stories, which embedded the identical central events within either conceptual or sensory details. Afterward, participants rehearsed the stories mentally, rated their experience, and later recalled the narratives aloud. Those memories of the shared central details, the story’s narrative, were then compared to the brain connectivity patterns.

What the Brain Remembers

The results showed clear linguistic and experiential differences. Stories rich in sensory imagery used more concrete language, while conceptual ones featured greater emotional and introspective expression. Both story types were recalled with similar accuracy, but participants described conceptual stories as easier to rehearse, more enjoyable, and recalled them with greater confidence. These behavioral differences mirrored distinct neural pathways, revealing how the brain “tunes” itself to different storytelling modes

Different Story, Different Pathways

When people encoded conceptually rich stories—those emphasizing thoughts and emotions—the hippocampus connected more strongly with the brain’s default mode network, which integrates personal meaning. In contrast, sensory-heavy stories activated regions that process sights and sounds. Both routes supported recall of the main events, showing that while the brain can reach the same destination, it takes different paths depending on whether a story speaks to feeling or perception. It seems memory is not just about storage but about interpretation.

This neural flexibility echoes ideas long explored in media theory—particularly Marshall McLuhan’s notion of “hot” and “cool” communication.

Memory’s Temperature

While Marshall McLuhan is best known for “the medium is the message,” he had many other important insights into media. For our purposes, hot and cold mediums.

Gutenberg and his cohort replaced a millennium of oral storytelling with text or print. For McLuhan, text is a “cool medium”— with few sensory cues, readers must imagine the sights, sounds, and emotions, effectively co-creating the story. Based on this research, this reflective engagement strengthens meaning-based networks in the brain, producing memories that emphasize emotional gist and personal insight rather than fine perceptual detail.

Today’s oral storytelling, podcasts, audio books, and talk radio sit midway between print and video. While still a cool medium, it invites participation, as listeners visualize what they hear, filling in missing details while also absorbing and entraining to words' rhythms and affective cues. This combination should foster hybrid memories, blending conceptual understanding with auditory-perceptual traces.

Visual storytelling exemplifies McLuhan’s “hot medium” by delivering high-definition sensory content with little for the audience to complete. The brain needn’t imagine, only absorb. These experiences create vivid, concrete memories that feel immediate and emotionally charged but are often less integrated into the viewer’s personal meaning frameworks over time.

This research may offer a neuroscientific context for McLuhan’s idea that a medium’s “temperature” shapes memory. Each form of storytelling activates a different balance of neural networks, each leaving a distinct imprint on how we remember what we experience.

This research may offer a neuroscientific context for McLuhan’s idea that a medium’s “temperature” shapes memory. Each form of storytelling activates a different balance of neural networks, each leaving a distinct imprint on how we remember what we experience.

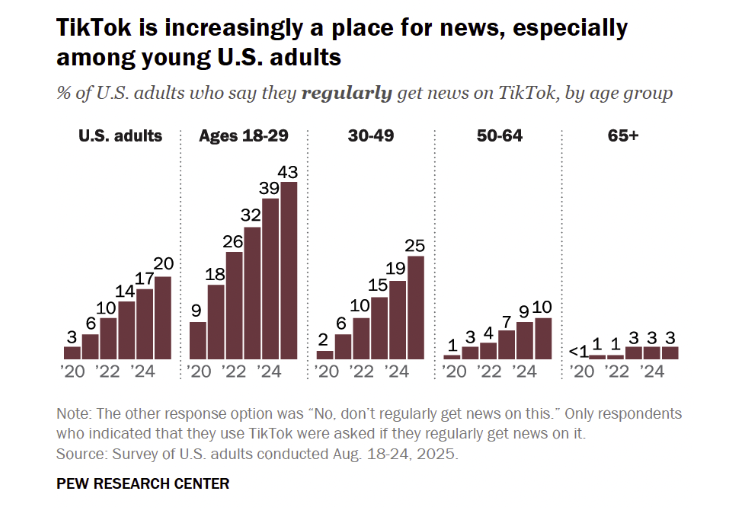

A recent Pew survey found that one in five Americans now get their news from TikTok—a distinctly “hot,” visual medium. Could these findings help explain why social media stories feel so immediate, yet sometimes fleeting? Future research may reveal whether our evolving media diet harmonizes—or clashes—with the way our brains are built to remember.

Why Stories Stay With Us

Whether a story is cool and conceptual, inviting our imagination to fill in the gaps, or hot and sensory, demanding our attention to detail, our brains adapt by forging distinct routes to remembrance. In a digital world where visual storytelling dominates, understanding how stories mold memory could illuminate why some stories linger as emotional truths while others fade as fleeting impressions. The science of storytelling reminds us that how we share shapes not only what we remember, but who we may become.

Source: Hippocampal-cortical networks predict conceptual versus perceptually guided narrative memory Journal of Neuroscience DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.1936-24.2025