In an effort to tie payment to the quality rather than the volume of service, CMS instituted star ratings for both health insurance plans (Medicare Advantage and Part D, which covers pharmaceuticals) and health facilities, such as hospitals and nursing homes. However, as John Warner writes in More than Words, echoing Goodhart’s Law:

“The more any quantitative indicator is used for social decision-making, the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.”

Nowhere is this more pertinent than considering healthcare quality metrics, including the CMS star ratings. For brevity, I will confine myself to the star ratings for health insurers, but the same forces are at work for facilities and systems as well.

Star Ratings Became a Payment Engine

CMS introduced the Medicare Advantage (MA) and Part D Star Ratings in 2007 as 1- to 5-star report cards to help beneficiaries compare plans. The Affordable Care Act later converted this report card into a payment system. Today, CMS rates MA contracts on up to 43 measures—spanning outcomes, process steps, patient experience, and access—while Part D plans are assessed on up to 12.

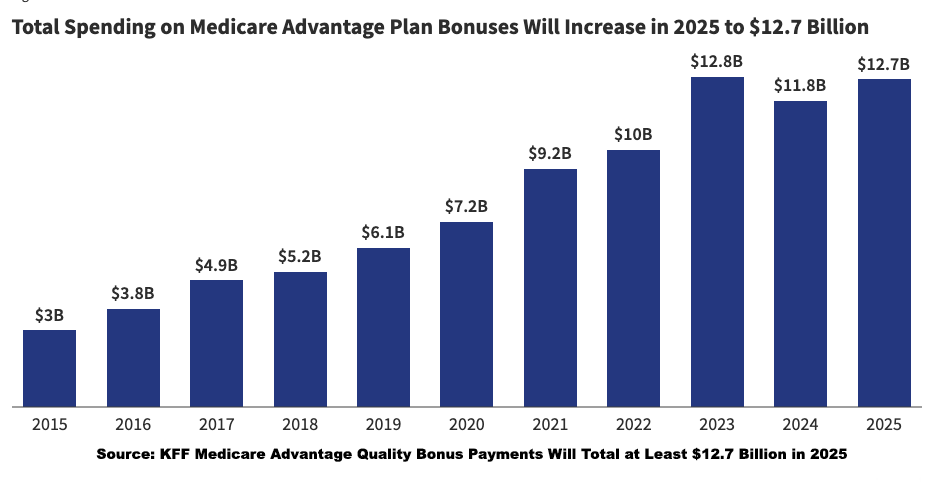

In 2015, CMS paid ≈ $3.0 billion in bonus payments to insurers. KFF estimates that the payments will total $12.7 billion this year. These funds flow almost entirely to private insurers who then decide how much to plow into greater benefits or corporate margins. Four- and five-star plans may retain 70% of their bonus and apply the remaining 30% to beneficiary services. In today’s vertically integrated insurance landscape—where a single company may own the health plan, medical groups, and pharmacies—those funds can effectively circulate within the same corporate ecosystem, transferring funds from one pocket of the insurance company to another.

As star ratings became powerful financial levers, they also began to reshape the day-to-day realities of clinical care.

Metrics Replace Medicine

On paper, these measures serve as proxies for safety, effectiveness, equity, and patient experience, all useful benchmarks for progress toward paying for quality care. And some have indeed helped standardize elements of care. But once reimbursement, public reputation, and organizational survival hinge on those numbers, the measurement, not the actual quality being measured, becomes the target.

Paul Scherz, writing in The Pathologies of Precision Medicine, points out that many of these star metrics

“track the particular actions medical practitioners take, such as prescribing a statin for someone with high cholesterol or metformin for someone with a higher risk of diabetes.”

The benefit of health outcomes is displaced by a more measurable good, risk reduction. On its face, that’s reasonable: process measures are easier to define and audit than clinical outcomes that require nuanced risk adjustment. But as process metrics become tightly coupled to payment and public ratings, they begin to displace the deeper goal of good care.

Scherz identifies another distortion: once the benchmark becomes the stake, clinical practice reshapes itself around hitting the metric. The result, he argues, is a “marginalization of clinical judgment.” The clinician is no longer solely weighing what is best for their patient in their life context, but is also tracking how prescribing or withholding a medication will affect their “quality metrics and thus reimbursement.”

From the clinician’s point of view, visits can begin to resemble risk-management checklists: Was the screening ordered? The statin prescribed? The counseling documented? When CMS stars reward uniform compliance with abstract targets, individualized judgment can feel like a liability, because the art of medicine thrives on responding to each patient’s unique circumstances.

At the same time, the structure of these metrics can unintentionally favor low-risk, highly compliant patients while making high-complexity or socially vulnerable patients “bad for the numbers.” In these moments, the art of medicine risks becoming subordinate to the arithmetic of quality scores.

These pressures on clinicians sit within an even larger ecosystem of financial incentives, where insurers have learned to adapt—and sometimes exploit—the star system.

Medicare Advantage Learns to Play the Game

These broader concerns are evident in how some Medicare Advantage (MA) plans respond to incentives. Practices such as risk upcoding—adding or emphasizing diagnoses to increase reimbursement—are now well documented. So is the tendency to enroll healthier individuals who require little care. A recent STAT analysis suggests that MA plans may also avoid people just turning 65 or enrolling for the first time, because many have deferred costly care during years on high-deductible plans. When they finally reach Medicare eligibility, that care comes due. As STAT writes, “The high deductibles for working-age people are coming back to bite insurers.”

And unsurprisingly, in a high-stakes bonus system delivering $10–13+ billion annually in bonus payments, we have litigation. United Healthcare, Humana, and Elevance Health, among others, are contesting, with varying degrees of success, the methodology and CMS determinations regarding star ratings.

Academics have weighed in, noting that much like grade inflation at Harvard, where 60% of the grades are A, 80% of the MA programs are rated four stars or higher. And there is the little problem that “plans eligible for enhanced bonuses have not shown greater improvement in measures related to clinical quality or administrative effectiveness.”

These distortions invite a deeper question: what happens when measurement itself eclipses the mission of care?

When Metrics Outshine Meaning

“Measurement turns the qualitative into the quantitative, the vague into the precise,” writes Anil Seth. Measurement is essential for understanding and improvement, but the danger lies in mistaking the score for the thing scored. In the CMS star world, incentives, data systems, and managerial priorities often align around the metric itself. The question is whether this alignment, when quality becomes a number to hit rather than a relationship to honor, pulls clinical practice quietly out of alignment with the actual good of patients.