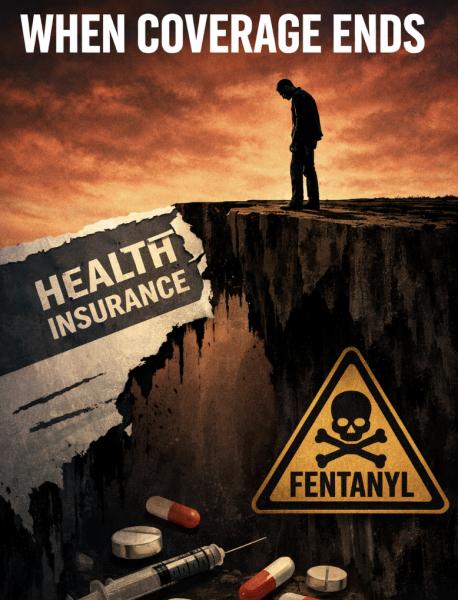

Paul lost his health insurance after being laid off. When his chronic pain worsened, he couldn’t afford a doctor. He turned to pills from a friend, then a dealer.

That vignette from my research is not melodrama. It is the logic of American health policy, where coverage is conditional, treatment is fragmented, and survival often depends on your deductible. When we weaken these systems, we sever vital links that prevent a personal crisis from becoming a casualty. Overdoses are not random tragedies; they are the foreseeable fallout of a system that withdraws support, leaving individuals alone to face the combined weight of poverty, social isolation, and policy neglect.

On January 1, 2026, we made that neglect measurable.

The Affordable Care Act’s enhanced premium tax credits—the insurance subsidies that helped millions afford Marketplace plans—expired. Analysts have warned that premiums for Marketplace enrollees would more than double on average without an extension. The Urban Institute projected that letting the enhancements lapse would push about 4.8 million people into uninsured status in 2026.

Coverage losses are often discussed as a budget score or a partisan talking point. They are a risk factor. Here’s why failing to restore these subsidies is likely to increase both opioid use disorder (OUD) and opioid overdose deaths (OOD).

Insurance is more than a card—it’s a protective factor

People without insurance have less access to health care, receive lower-quality care, and have worse outcomes, including a greater likelihood of OUD and OOD. In the United States, historically about 18% of nonelderly adults with OUD have been uninsured—a baseline that is set to surge as the safety net is pulled back.

That number is policy-sensitive. When subsidies disappear, some working families will “choose” to go uninsured, but they are forced to make the choice because of the price of insurance. And when people fall off coverage, they don’t just skip annual physicals. They lose the protective scaffolding that keeps pain, depression, and addiction from turning fatal: stable primary care, mental health treatment, non-opioid pain options, and timely access to evidence-based medications for OUD.

Lynn R. Webster, MD, is a pain and addiction medicine specialist. He is Senior Fellow, Center for U.S. Policy. Dr. Webster is the author of the forthcoming book, Deconstructing Toxic Narratives—Data, Disparities, and a New Path Forward in the Opioid Crisis, to be published by Springer Nature. He is not a member of any political or religious organization.

It gets worse in the exact places the overdose crisis already hits hardest: communities where poverty exceeds the average. Insurance status acts as a proxy for poverty or low income. Medicaid covers nearly half of nonelderly adults with OUD. The people most likely to lose subsidized Marketplace coverage are often those who make “too much” to be eligible for Medicaid but not enough to absorb a sudden premium shock, especially in states with limited safety nets. In these communities, insurance serves as the vital mediating factor that prevents economic distress from spiraling into a mortality crisis.

Overdose risk rises when systems destabilize

Social determinants of health operate across multiple levels and account for up to 90% of health outcomes. Removing subsidies is not a narrow insurance tweak. It is an upstream economic stressor that ripples downstream as relapse, untreated pain, worsening mental illness, and delayed care.

While the link between economic stressors and opioid outcomes is complex, research identifies certain vulnerabilities. A landmark 2017 county-level study found that a 1% increase in unemployment was associated with a 3.6% increase in the OOD rate (and a 7% increase in opioid-related ED utilization). The impact of economic shocks often depends on the strength of the safety net. When premiums jump and coverage drops, families face new medical debt, worsening financial strain, and job lock — the very same stressors that overwhelm resilience and incubate substance use.

And when uninsured people do reach the health system, it’s often later than is ideal. The National Inpatient Sample concludes that patients with “no payment method” were admitted more often than those with other payer types, and the U.S. pattern is blunt: “…treatment often depends not on need, but on network.”

This is how preventable illness becomes emergency care; how emergency care becomes discharge without continuity; how discharge becomes the street supply; and how the street supply, now dominated by fentanyl, becomes death.

“Overdoses are falling” is not a plan

Even if some national overdose indicators improved recently, that does not immunize us against policy-driven backsliding. The fentanyl era punishes instability. When people cycle in and out of coverage, they cycle in and out of treatment. When they lose opioid tolerance during coverage gaps and return to an illicit supply, the margin for error disappears.

Subsidies are not a cure for addiction, but they are part of the infrastructure that prevents addiction from becoming fatal.

What Congress should do now

Extending (or reinstating) Marketplace subsidies is harm reduction at scale. It keeps people connected to care before crisis, lowers churn, supports treatment continuity, and reduces the financial shock that drives despair. It is not charity.

Extending subsidies is not a long-term solution. Our health care system is broken, and insurance is a major contributor to that dysfunction. If lawmakers want fewer overdoses, they should stop treating coverage as a temporary perk and start treating it like public safety. They should restore enhanced Marketplace subsidies and prevent coverage cliffs.

They must pair affordability with access. This means that they must expand provider capacity for OUD care and strengthen networks so coverage actually functions. And they have to address the upstream drivers—poverty, housing instability, and economic dislocation—that make opioids more attractive and recovery less achievable.

The opioid crisis is not primarily a story about molecules. It is a story about systems. When we weaken the systems that keep people connected to care, we leave them exposed to the harshest effects of economic instability.

We can predict that. And we can prevent it.