In 2018 restaurant menus were required to list calorie counts, "to support informed consumer choice, reduce caloric intake, and potentially encourage restaurant reformulations." Since a majority of Americans eat in fast and slow food restaurants (or COVID induced take-out), a reduction in caloric intake here would have a significant effect on reducing our weight, especially since we tend to underestimate our caloric choices. The researchers sought an additional benefit of the regulation, a reduction in disease, in this case, their favorite condition to study, cardiovascular disease.

Taxes of sugary beverages have been with us for some time, with variable results. The second study considered three approaches to taxes seeking the one yielding the most substantial savings.

- Volume tax – taxation based on the volume of beverage purchased

- Tiered tax – a progressively increasing tax as the concentration of sugar increases

- Absolute tax – a tax based on the total amount of sugar present in the beverage.

The researchers used a "validated microsimulation" of cardiovascular disease, treatment, and costs using as their evidence-base, survey data from the National Health and Nutrition Examinations Surveys (NHANES). NHANES dietary habits were based on recall by participants, which introduces some uncertainty. The validated microsimulation is a black-box as the source-code is "not publicly available." As to validation, the model was 80% predictive of the actual values at five years.

The assumptions were, in most part, reasonable, evidence-informed choices. There were a few notable exceptions. In the labeling study, almost half of the data used to make their assumptions came from supermarkets, vending machines, and laboratories where national labeling did not apply. And while the researchers report that the population's demographics were reasonably consistent, two-thirds of the labeling data was missing racial data and a quarter of the socio-economic data making that statement by researchers more opinion than fact.

In the labeling study, the model utilized modest reductions in calories, 19 calories/day if the food was unchanged, 44 calories/day if the food was reformulated. By reformulation, the researcher reference manufacturer initiated changes in food content to make their labeling appear "better" – a response to consumer's "demand." The tax study used a reduction in consumption of roughly 25%, which is consistent with a price increase of about the same percentage. Both studies used the now estimated reduction in sugar to estimate the decrease in BMI [1]. In turn, the BMI was utilized from studies for cardiovascular disease to estimate a reduction in cases – so a lot of estimating going on.

The most significant assumption is the one hiding in plain sight – that the public is only afflicted by heart disease and diabetes. Other conditions that may be altered are safely ignored when your interest is cardiovascular disease, not a more expansive view of population health that includes cancer, accidents, and lung disease.

As you might expect, both labeling and taxation resulted in less disease and their associated costs. The benefits accrue to younger patients, in their 30's and 40's as well as to black and Hispanic populations where soda consumption is higher. That racial benefit is also associated with a higher cost to those populations, as sugar taxation is a regressive tax. The model's output was most sensitive to the number of calories consumed and the pass-through rate of the tax to consumers.

"Our model cannot prove the health and cost effects of these SSB tax designs in US adults. Rather, the estimates provide evidence that can be considered and incorporated into the design, implementation, and evaluation plans of SSB taxes, including at local, state, or federal levels."

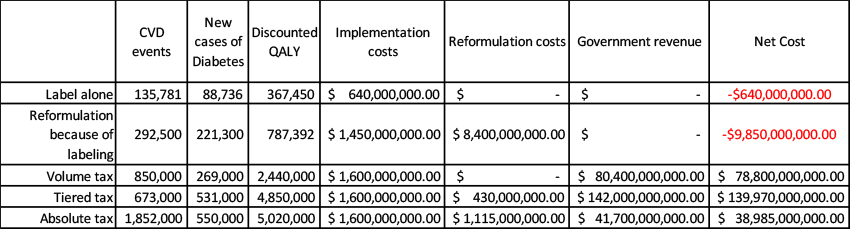

With that statement from the researchers in mind, let us consider which regulatory approach, labeling, or taxation you might choose. The summary data of the two studies are condensed into these table.

The first three columns show the estimated impact of reducing sugar on reducing cardiovascular events, diabetes, and the resulting changes in the quality of one's life. Any reduction seems to help, but that absolute tax has the greatest impact. The next three columns consider the cost to gain those benefits. Implementation costs refer to spending by the government to write and enforce the laws, as well as collect the taxes in the tax scenarios. It also includes the cost to restaurants and manufacturers for changing labels. Reformulation costs are estimated spending by manufacturers as they reshape their products based on consumer response to the new labels and taxes. Labeling has a small effect on reformulation costs; an absolute sugar tax provided the greatest nudge to reformulation. Government revenue is, of course, the amount of taxes being paid.

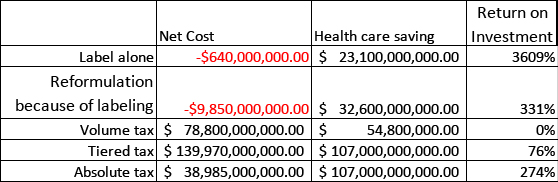

Net cost is a bit misleading. In the labeling argument, the expenses are "borne" by the manufacturer. In the tax argument, those costs are to the consumer. In both instances, these costs may be absorbed by the manufacturers or restaurants, but in most situations a percentage, in this case, 75% is passed through to the consumer. More importantly, when we talk about costs, remember that the consumer is the one spending the money, in higher prices or taxes – there is no free lunch or beverages. Health care savings were taken from the papers and reflected estimates of direct costs of care as well as indirect costs in terms of productivity and impaired life quality.

In the final column, I compute a return on investment – for the additional money spent, how much do we save. This is the place where the policymakers tradeoff cost and benefits. If we were all to read labels and make wise choices, we would get the most bang for our buck. Of course, that is not what humans do. The argument for most sin taxes is that we need to be nudged along. Of all the tax schemes, an absolute tax on the quantity of sugar present provides the most significant value, an ROI of 274%. But that value is less than the return on investment of market-driven reformulations at 331%.

Regulations reducing the quantity of added sugar by manufacturers will provide the highest return on investment. Taxation will return the most significant benefit. Which would you choose?

[1] To make this calculation, the researchers needed to convert caloric reduction to BMI, the factor, among others, that drives cardiovascular disease and diabetes. They provide a 3-page discussion in the supplement but conclude that a 55 calorie/day reduction results in one lost pound over the year and that this new weight loss is permanent. Your own experience with dieting can inform you as to the plausibility of a consistent weight loss. And you may wonder how sensitive the model is to weight when losing 5 ounces will result in nearly 15,000 fewer cases of cardiovascular disease and 21,000 cases of diabetes. Since the model is "not publicly available," I suppose we will never know.

Source: Health and Economic Impacts of the National Menu Calorie Labeling Law in the United States Circulation Cardiovascular Quality Outcomes DOI:10.1161/circoutcomes.119.006313

Health Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Volume, Tiered, and Absolute Sugar Content Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Policies in the United States Circulation DOI: 10.1161/circulationaha.119.042956